CAA News Today

How to Become an Art Editor: An Interview with Phil Freshman, President of Association of Art Editors

posted Jun 12, 2018

Freshman’s home office. All photos courtesy Phil Freshman.

Phil Freshman is a freelance art editor and president of the Association of Art Editors (AAE). Formerly a staff editor at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (1980–84), the J. Paul Getty Museum (1985–88), the Walker Art Center (1988–94), and the Minnesota Historical Society Press (1995–99), he has worked on numerous books, exhibitions, and other projects, focusing mainly on art history, architecture, photography, and design.

We were curious what advice Phil might have for aspiring art editors. CAA media and content manager Joelle Te Paske spoke with him in April 2018.

Joelle Te Paske: I’m glad we have a chance to talk, especially to learn more about the Association of Art Editors and take a look at what you do.

Phil Freshman: When I talk to people about the AAE who didn’t know about it previously, they’re typically glad to know it exists.

JTP: It’s great. So, what are you working on nowadays?

PF: The last catalogue I edited was for the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, which recently took the “s” off its name and started calling itself “Mia.” Anyway, the book was about contemporary Japanese lacquer sculpture, and was tied to an exhibition that is on view now and will be up until late June. It’s a field of study I had never thought about much. You think of Japanese pottery, right? But you don’t think of pure sculpture. A very interesting and challenging project.

Right now, I’m editing a memoir by a lifelong friend who recently retired from the law. He spent a year hoofing it around West and East Africa in the early 1970s and thought he would get around to writing a memoir right afterward. Then 45 years went by like the wave of a hand, and here he is, doing it now. So, it’s a pleasure to help him, to know enough to make his manuscript better.

JTP: You’re learning a lot about him, I bet.

PF: I am. And that was a part of his life I hadn’t known much about to begin with.

JTP: How did you become an editor?

PF: I was a Los Angeles lad who first wanted to be a newspaper reporter. But despite trying for several years, it didn’t work out. I then lived for three uninterrupted years in Israel, Iran, East and West Africa, and Spain, finding ESL teaching jobs along the way. I came back home to get an ESL degree at UCLA. During that time, a friend in LA whose firm published books dealing with Western US history hired me part-time to review slush pile manuscripts and proofread book galleys.

A couple of years later, with just that little bit of experience but intrigued by the work, I applied for a copyeditor-proofreader job at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. I took the required test (along with something like 200 other applicants), was interviewed, and then hired. I thought, “Oh, God. Now I actually have to do something.”

JTP: Yes, now it was real!

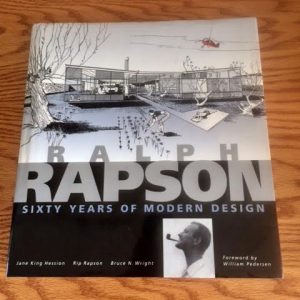

Ralph Rapson: Sixty Years of Modern Design (1999). Freshman edited this and the other books illustrated here.

PF: At first, I had no idea what I was doing. But my senior editor was a great teacher. When he left the museum—too soon, alas—I was the only editor there. I worked on books about American painting and printmaking, 18th-century fashion, contemporary art, and more, plus the monthly members’ magazine, annual reports, lots of brochures, flyers, exhibition labels. It was full immersion and very long weeks until, after six months, I was allowed to hire somebody. Eventually, I had three editors.

JTP: That makes sense. Rather than just one, working at that scale.

PF: Right. But when I was hired from the Getty Museum to be the Walker Art Center’s first-ever editor, in 1988, I was once again a solo act—and remained one for three years. The Walker had an ambitious program of publishing catalogues and presenting exhibitions on the history of graphic design, Russian Constructivist art, contemporary sculpture, and this, and that, and the other thing! All that plus editing for the Walker’s very active film, performing arts, and PR departments. I worked 70 to 80 hours a week, and that didn’t stop even after I was finally able to hire an assistant editor.

JTP: There was no getting around the fact that you had to go through all that material.

PF: Right. Not just going through it all but also needing to be attuned to a constellation of details. That was, as it so often is, the job—the details, as well as panning out for the whole picture. And more often than not, I didn’t receive all the materials I needed at the get-go. Unfortunately, that’s all too typical in this racket. In fact, sometimes you get a little bit, and then some more dribbles in, then a bit more, and you have to assemble the material as it’s unfolding before you, make everything hang together. I had to develop a host of skills over the years, including diplomacy—at which I’ve never been adept.

Beyond all that, one reason I was initially attracted to editing was that I had no patience for formal schooling. I’ve found that editing has provided a rich, ongoing education in which I get a front-row seat to subjects about which I might otherwise never have learned a thing. Not to mention exposure to fascinating people, and to situations I wouldn’t have encountered if I weren’t doing this work. There are certainly things to hate about it, but the balance sheet works out in its favor.

JTP: It’s so detail-oriented, but you are committing your time to new projects and scholarship. It’s integral to the work.

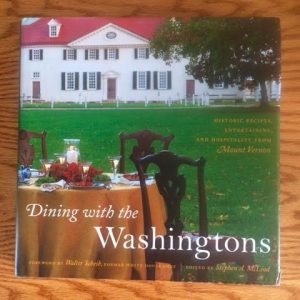

Dining with the Washingtons: Historic Recipes, Entertaining, and Hospitality from Mount Vernon (2011).

PF: Yes. And I also keep coming back to this: you have to keep asking questions. One instinct that made me want to be a reporter applies perfectly to editing. I ask questions, and then ask more, and then ask some more. Often enough, I’ve had authors and curators who are responsive to that. The relationship works best when they understand that I’m on their side, trying cover any holes that open up because they were writing too fast. But some of them are resentful, insecure, brittle, and they can make that sort of thing difficult.

JTP: Yes, I can see it going both ways. I would think, though, that writers with more experience realize having a good editor can be like a good friend, someone who can make your work better before it goes out into the world.

PF: That’s it. I’ve worked with a few pretty well-known authors with whom it felt like a collaboration. They liked the back-and-forth. They didn’t just take all of my suggestions but said, “No, let’s discuss this further.” And then you get to a middle way that’s better than what you thought of, or than what they thought of.

JTP: Would you recommend that editors who are just starting out keep that in mind?

PF: Definitely. Another thing I like to tell aspiring editors is, “Go to the library.” You know, the library?

JTP: I’ve heard of those.

PF: [Laughs] Get hold of exhibition catalogues and other art books on a range of subjects, and then review all the separate essays or chapters, the footnotes and bibliographies, the plates, figure references, checklists, and the rest. And bear in mind, as you’re reading, that it’s highly unlikely that the original manuscript was delivered intact to the editor at beginning of the process. Probably dribbled in over a period of weeks, if not months.

You have to take the bits and pieces and make them fully consistent, factually accurate, grammatically correct, and maybe even interesting! So, I don’t know that someone has to have an art background per se in order to be an art editor. But I would say that having a feel for and a knowledge of language, a willingness to become genuinely invested in a subject, a good visual memory, and an insane attention to detail are all necessary.

JTP: I imagine AAE would be a great resource for people starting out. Where else should they look?

PF: LinkedIn is a good source. The old cold-call approach is not bad. Find people who work where you might want to work and contact them. I recently spoke with an editor friend who, though she had just quit Facebook, found a valuable online organization on it called Editors’ Association of Earth. She described it as a private, heavily moderated group and a place where you can engage with other editors, ask questions freely, and get advice.

JTP: Editors likely want to share their skills—many have devoted their careers to sharing knowledge, after all—and it seems like that would be good for people starting out.

PF: I’d also suggest getting immersed in The Chicago Manual of Style. And finding books about editing. Here are some I recommend:

- The Subversive Copy Editor, by Carol Fisher Saller. University of Chicago Press, 2009. Her monthly online Q & A, via the U of Chicago Press Website is terrific. Need to sign up for it.

- Exhibit Labels: An Interpretive Approach, by Beverly Serrell. Rowman and Littlefield, 2015 (second edition).

- Line by Line: How to Improve Your Own Writing, by Claire Kehrwald Cook. Houghton Mifflin, 1985. (This is the one I have, but there are probably subsequent editions.)

- On Writing Well, by William Zinsser. Collins, 2006 (30th anniversary edition).

- The Copyeditor’s Handbook: A Guide for Book Publishing and Corporate Communications, by Amy Einsohn. University of California Press, 2006 (second edition). A very good primer on the basics. It also includes copyediting exercises and answer keys.

JTP: That’s terrific. Thank you.

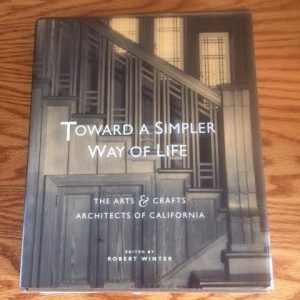

Toward a Simpler Way of Life: The Arts and Crafts Architects of California (1997).

PF: I’d also suggest that if a nearby college offers copyediting classes, take one. It can be very useful to learn the mechanics in a formal way. Such classes also help you see whether or not you have an appetite and instinct for editing.

JTP: This is important, too, because it’s an intensive practice.

PF: Right. Once you get involved in a job, it’s immersive. It is the writer’s book, the museum’s book, the publisher’s book, but you can’t ever say to yourself, “Well, it’s on them. I wash my hands of this,” or, “It’s not going to have my name on it.” You have to feel responsible for whatever project you’re on. In other words, you can’t say, “It’s just a job.”

Another thing to consider: Back in the days when I had stars in my eyes, I’d think, “How wonderful it would be to work for XXX Museum of Art. So prestigious.” But in fact, some of my best experiences have been with smaller institutions and some of my worst with larger, “important” ones.

JTP: That’s good to know.

PF: Usually, there are good people in such places. Sometimes a good attitude. Less bureaucracy. And often you can get things done more fluidly.

Another thing important to me is having solid relationships with graphic designers. I’ve worked with good ones and very bad ones. By good, I mean ones who like to share suggestions about what might work, ones who welcome it when you point out why a certain typeface, or size of type, or caption location in relation to pictures might be reconsidered. It’s a conversation. And then on the other hand, there’s the head-banging-against-the-wall experience of having to deal with the other kind of graphic designer. One of them referred to text as “texture,” something mostly useful as a visual complement to their brilliant layouts!

JTP: As an editor, I can only imagine [laughs]. Do you ever work in tandem with a graphic designer, presenting yourselves to a client as a team?

PF: Yes. Several designers I know will get a job and say to the client, “I know a good editor in Minneapolis. I’d like you to hire him.” By the same token, I’ll get a job and ask, “Do you have a designer for this?” If the client says no, I’ll offer contact information for three or four designers, making my top preference clear.

JTP: Good to know. Keeping track of the designers you like working with would help you establish a mutual-support system.

PF: That’s right. It helps you feel more comfortable going into a project—you know that you can kid around with the graphic designer, and that you can bitch about the client without worrying it’s going to get back to them.

JTP: Can you name a highlight of being president of AAE? Also, how long have you been president?

PF: I’m president for life [laughs].

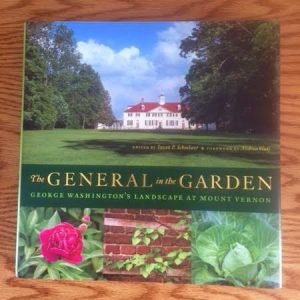

The General in the Garden: George Washington’s Landscape at Mount Vernon (2015).

JTP: [Laughs] Like a Supreme Court justice.

PF: You got it. I’ve occasionally had thoughts of not doing it anymore, but it’s not [too taxing]. Well, creating the first version of our soup-to-nuts style guide, in 2005 and 2006, which I did in tandem with three other editors whom I greatly respect—that did take months. But the result was just wonderful. I’m really proud of having done that. And I get lots of good feedback. Also, I like helping editors find work through the job opportunities page.

There’s also a section [on the AAE site] called Helpful Links. It has many sources you might want to refer to as you’re doing research for a book or an exhibition you’re editing.

The site is an open-source one. Anyone can use it freely. One AAE offering not visible on the site, however, is the rates survey we conduct every five years. It includes questions such as “How much do you charge for editing, proofreading, and other separate tasks?” And “Do you charge extra for working on weekends?” Among numerous others. We sort the answers, and provide a report with graphed percentages and selected verbatim responses.

JTP: That’s terrific. Sounds like it would help editors advocate for themselves.

PF: That’s the idea, of course. I don’t post rates-survey reports on the website because I don’t want potential clients, such as curators, browsing them and thinking, “Wow! Looks like I can get away with paying somebody $20 an hour!” But I’m happy to send the reports out to anybody who requests one.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.