CAA News Today

International Review: L’Algérie de Gustave Guillaumet by Roger Benjamin

posted Oct 26, 2018

The following article was written in response to a call for submissions by CAA’s International Committee. It is by Roger Benjamin, professor of art history, University of Sydney, Australia.

Exhibition review: L’Algérie de Gustave Guillaumet (1840-1887), Musée des Beaux-Arts de La Rochelle (France), June 8-September 17, 2018

In a most unassuming regional museum in France, an exhibition of real art-historical significance opened this past June. For the first time since 1899, the work of the preeminent French Orientalist painter of the later 19th century has been brought together. Gustave Guillaumet is not an obscure artist, as every survey of Orientalism since the great Royal Academy show of 1984 has included his paintings. But the scholarly work had not been done until now, when the fruits of Marie Gautheron’s 2015 doctoral dissertation on the desert and Guillaumet have been brought to bear (Gautheron, M., L’invention du désert: émergence d’un paysage, du début du XIXe siècle au premier atelier algérien de Gustave Guillaumet (1863-1869), Paris Nanterre University).

Fig. 1. Gustave Guillaumet, La Famine en Algérie, Salon of 1869, oil on canvas, 122 x 92 in (309 x 234 cm) Le Musée National Public Cirta de Constantine, Algeria (restored for the exhibition).

Many of the works on view in La Rochelle are unfamiliar, coming from regional museums, the artist’s descendants, private enthusiasts, and storage collections of the Musée d’Orsay. The largest single work was thought to have been lost. The Famine in Algeria (Fig. 1), the most disturbing large scale canvas at the Salon of 1869, was known only by a poor woodcut and several drawings. Its subject was altogether too tough—the cadaverous members of two Arab families expiring on the pavement of a city in what was (in French law) a department of France, the province of Algiers in Algeria.

La Famine had been languishing, rolled up and torn in the basement of the National Public Museum of Constantine, Algeria (Le Musée National Public Cirta de Constantine). The research of Dr. Gautheron located it, and through the goodwill of Algerian curators and the political weight of Maître Salim Becha (an Algiers-based lawyer, art collector and philanthropist) the work was sent to France for restoration. A successful crowd-funding campaign led by Annick Notter, chief curator at La Rochelle, paid for the conservator Pascale Brenelli, who spent nine hours every day from early February until mid-June resurrecting the picture.

Guillaumet’s ghastly image of a baby suckling at the collapsed breast of its dead mother goes back through Eugène Delacroix to Nicolas Poussin and classical precedents. Entirely new, however, is his angular figure of an emaciated Arab father who, supporting his fainting teenage son, reaches up for a loaf of bread being handed down from the tiny window of a prosperous home. The outstretched hand is female, bejeweled and, through the curvature of its fingers, evocative of the Jewish beauties painted by Chasseriau in Constantine (1846) and by Delacroix in Tangier (1832).

La Famine’s grisly treatment was probably influenced by photographs of the dying taken in situ. Catalogue author (and leading historian) Jacques Frémaux estimates one third of the indigenous population of Algeria died in the famine of 1866-70, due to drought, locust plague, cholera, and the expropriation of farmlands by European settlers. La famine is unrelieved by aesthetic ‘sweet spots’ like the majestic horseman that Delacroix placed in his Massacres of Chios. We have instead the moral and visual austerity that pervades Guillaumet’s work. A grave witness to these events, Guillaumet was not about to beautify them.

Fig. 2. Gustave Guillaumet, La Séguia, près de Biskra, oil on canvas, 1884, Salon of 1885, 39 x 61 in (100 x 155.5 cm), Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

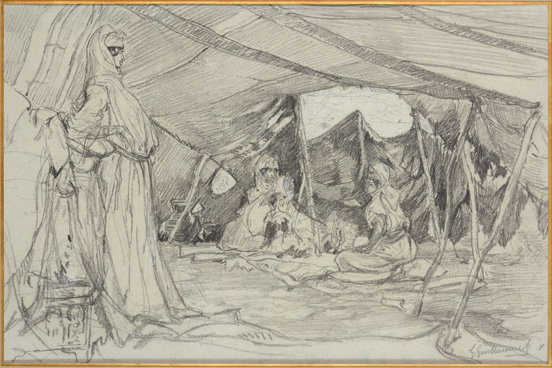

Almost all of the artist’s best-known landscapes are on view, including The Sahara of 1867, with its camel skeleton and mirage at the horizon with a setting sun, and the dazzling Séguia, Biskra (Fig. 2) of 1884. (Both are usually on display at the Musée d’Orsay). The loan of numerous restored pencil drawings and watercolors from the Orsay was intended to show the genetic relationship between such studies and the resultant tableaux by Guillaumet (who narrowly missed the Prix de Rome for landscape and ended up heading to Algiers in 1862 rather than Rome). (Fig. 3)

It came as a shock to learn that many of these drawings could not be exhibited on the second floor of the eighteenth-century mansion that houses the Musée de la Rochelle, as it was condemned by city architects one week before the scheduled opening. Despite the best efforts of the staff, this major exhibition was opened in almost third world conditions: a building with the floor above held up by a dozen massive steel columns, no air conditioning, and inadequate spotlighting. Yet historic La Rochelle is a wealthy city, with a new 5,000-boat marina and an opulent public library, the Mediathèque, nearby. City and provincial authorities must reward the enterprise of its art curators by providing an adequate home for future temporary exhibitions and permanent collections.

Fig. 3. Gustave Guillaumet, Sous la tente, graphite pencil on paper, 9.5 x 17 in (24 x 44 cm), private collection. Photo: A. Leprince.

Fortunately, L’Algérie de Gustave Guillaumet will travel to two other regional museums in much better condition: the Limoges Fine Arts Museum and the celebrated La Piscine, a converted Art Nouveau baths complex in the northern city of Roubaix. And happily, the catalogue, a scholarly book with first-class production values and superb plates, perfectly represents the project. Its backbone is the set of four chapters by Gautheron, a former academic teaching art history and visual culture at the École normale supérieur de Lyon, along with detailed entries on key works and a documentary apparatus at the end. Gautheron was careful to enlist a range of other writers, including Algerian literary figures like Leïla Sebbar, and art historians from Algeria, the United States, Australia, France, and Ireland. For her part Gautheron has also completed a 300-page monograph on Guillaumet that is awaiting publication.

Fig. 4. Gustave Guillaumet, Habitation saharienne (Cercle de Biskra), Salon of 1882, oil on canvas, 58 x 68 in (146.1 x 173.4 cm), Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Virginia, gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr.

Guillaumet, like the admirable Eugène Fromentin before him, traveled initially in Algeria in close connection with the officers of the French army and its political wing, the Bureau Arabe. His stunning series of interiors of Arab houses, made in the oasis villages of Biskra and Bou-Saâda, were made possible by the intervention of the Commandant’s wife (as the artist narrates in his text “Les intérieurs,” from his book Tableaux Algériens). Crowning the series but absent from the exhibition was the key Guillaumet work in America, Saharan Dwelling (Fig. 4), recently loaned by the Chrysler Museum of Norfolk Virginia to the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris (see the author’s Biskra, Sortilèges d’une oasis, Paris and Algiers, 2016, pp. 90-91). Scenes of women and their daughters working at looms, the first of their kind and highly influential on the next generation, complement Guillaumet’s earlier assemblages of men, camels and horses on the barren plains—at prayer, at market, or on a military bivouac. Guillaumet, an admirer of J. F. Millet, produces high naturalism, except in one key respect: he always excludes the colonizer and his works. Absent are the soldiers in uniform, colonists directing Berber farmworkers, the modern buildings and telegraph wires at Bou-Saâda, the military hospital at Biskra where the painter convalesced in 1862, or the British tourists who by the 1880s were encumbering the desert scene. Guillaumet’s vision is not a “painting of modern life” as exemplified by the traveler Constantin Guys in Istanbul. It is an image of Algeria as it used to be: a country and a people that won the admiration of foreign travelers, intellectuals and officers, even as their invasive actions helped bring about its demise.