CAA News Today

Environment in Practice: Artmaking through Crisis

posted May 10, 2018

The following article was written in response to a call for submissions by CAA’s International Committee. It is by Frederico Câmara, artist and independent researcher, Sydney, Australia.

Fig. 1. Researcher Killian Quigley chairing a conversation between Bill Fox, Janet Laurence, and Ian Maxwell at the event Artists Have Never Been More Important, at the University of Sydney. Photograph: Eloise Fetterplace

Something very important for the planet is happening in Australia. As the Great Barrier Reef suffers from coral bleaching, and scientific evidence of global warming accumulates, the Sydney Environment Institute (SEI) raises the question: What can artists do in response to environmental crises?

The SEI at the University of Sydney addresses key environmental questions through discussion, research, and collaborations between artists, scientists, and humanists. This article discusses two recent international art events hosted by SEI to illustrate their work.

The first was held on March 27, 2018, at the University of Sydney. It featured William (Bill) L. Fox, Director of the Center for Art + Environment (CA+E) at the Nevada Museum of Art in a dynamic conversation with artists and members of the public on why “artists have never been more important”. This program was followed the next day, March 28, by the conference Environment in Practice: Artmaking Through Crisis, which gathered environmental activists, visual and sound artists, photographers, writers, musicians, and theater artists showing a wealth of artistic production that originates from, celebrates, and ultimately cares for the natural environment. In both events, participants were invited to exchange ideas on individual and communal artistic strategies to deal with the pressing environmental issues of today, through art.

Fig. 2. Dean Sewell / Oculi, El Niño (ongoing). Photograph.

Bill Fox’s talk, Artists Have Never Been More Important, was a masterclass on artists working with the environment—as material, site, and subject—from well-known examples of American Land Art, to more environmentally conscious, if less spectacular, responses to various challenges involving humans and the natural world. It was interesting to note that those different approaches are not a sequential progression from one to the other. Both happened in the past, and are still happening now. Fox also introduced the work of the CA+E, an institution that collects the archives of artists working with the environment, and promotes research in the field. He concluded by proposing the idea of the artist as a bridge between scientists who collect evidence of climate change, and politicians who create and implement environmental policies. A lively conversation ensued with responses from artist Janet Laurence, theater theorist Ian Maxwell, SEI postdoctoral fellow Killian Quigley, and the audience, with one of its members arguing for a broader, less limited role of art in addressing the many crises that afflict our environment (Fig. 1).

This criticism is reflected in what the convenors called the “instrumentalization” of art in their introduction to the conference, questioning how artists will respond to the various invisible signs of environmental crises that defy representation and narration, including rises in temperatures, changes in the chemistry of oceans, and the scale of geological time. What are the possibilities for artmaking through environmental crises that will not reduce artistic practice to an instrument for the communication of scientific findings? Are artists capable of formulating their own questions, designing their own methods (including the collection of data during fieldwork), and producing and disseminating new knowledge and art that will criticize, reimagine, honor, and shape the world into a better place?

Fig. 3. Merilyn Fairskye, Fieldwork II (Chernobyl), 2009. Single-channel video, silent, 100 minutes.

The conference featured four thematic sessions, each one including artists working with a multitude of topics and methods. Session 1: “How Do Images Act,” began with David Ritter, CEO at Greenpeace Australia Pacific, who discussed the importance of images in the service of environmental activism and the challenges in using photography in an image-saturated world. He described his collaboration with photographer Dean Sewell who presented works at the conference on environmental issues affecting his native Australia and beyond (Fig. 2). The last speaker in this session was Merilyn Fairskye, an artist who travels the world in search of nuclear sites. She presented Fieldwork II (2009), a work filmed in Chernobyl that conveys the invisibility of nuclear evidence through the uncanny effect of movement at the level of pixels (or atoms?), as a symptom that that landscape is ill (Fig. 3).

Session 2: “Engaging Extremity,” started with sound artist Philip Samartzis presenting sounds that he documented during two scientific expeditions to Antarctica, creating an “overlooked” sound ethnography of the Australian presence on that continent. David Burrows then showed his stereoscopic photography in installations that transpose the Antarctic landscapes into the urban fabric of the city or the desert, demonstrating the idea of environmental unity where, apparently, there is none. Film theorist Belinda Smaill responded by remembering the participation of artists in the early navigations of discovery, linking their work to a contemporary, though decolonizing, environmental practice.

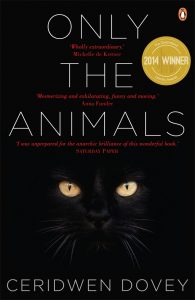

Fig. 4. Ceridwen Dovey, Only the Animals. Published by Penguin Random House Australia.

In Session 3: “Surpassing Humans,” writer Ceridwen Dovey presented her short story collection Only The Animals (2014), in which animals narrate their own deaths as a result of human conflicts, an exploration of the voice and consciousness of animals and a tribute not only to animals but also to other authors who have used a similar strategy (Fig. 4). Poet Judith Beveridge read two of her poems, highlighting the importance of metaphor as a tool for exploring relationships between humans and nature, and engendering in her readers a sense of wonder of the natural world. As she described it, she writes poetry “to give the natural world centrality” in an era of anthropocenic extinction.

In Session 4: “Composing Loss,” Genevieve Campbell, musician and music researcher, presented the project Ngarukuruwala – We Sing Songs, a musical collaboration with a group of senior song-women on the Tiwi Islands of Australia that emphasises the links between people, culture, and the land, and the need for preservation of both natural and cultural landscapes. Michelle St Anne performed My First Memory, a gripping monologue exploring the artist’s first memories and sensations of images, sounds and smells, to reflect on the domestic environment of her family home, perhaps as a metaphor for the natural environment as our collective home, and its disruption through conflict (Fig. 5).

The conference concluded with a discussion chaired by Killian Quigley on the possibilities for future developments and possible outputs. As the feminist and LGBT theorist Annamarie Jagose pointed out in her welcome speech, the conference itself, with its presentations and discussions, constituted one of the many forms that art can take as a practice that deals not only with the plights of the natural environment, but also recognises its capacity for wonder through beauty.

A full program and biographies of the speakers can be found here.

Podcast: Artists Have Never Been More Important

Fig. 5. Michelle St Anne performing “My First Memory” in I Love Todd Sampson (redux) at 107 Projects, Sydney, Australia. Photography: Clare Hawley