CAA News Today

International Review: Heaven and Earth in Chinese Art by Yiqian Wu

posted Jun 04, 2019

Exhibition Review: Heaven and Earth in Chinese Art: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei, February 2 –May 5, 2019, Sydney, Australia

The following article was written in response to a call for submissions by CAA’s International Committee. It is by Yiqian Wu, a graduate student at the University of Sydney.

Figure 1. Exhibition banner. The Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. February 5—May 5, 2019. Photo: Yiqian Wu.

How should we humans perceive our relationship with nature? An ancient Chinese perspective of the human/nature relationship was offered by Heaven and Earth in Chinese Art: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei (Fig. 1), which was recently exhibited at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. This exhibition offered the viewer a rare opportunity to closely examine eighty-seven Chinese national treasures with the themes of “Heaven and Earth,” “Seasons,” “Places,” “Landscape,” and “Humanity.”

This article focuses on three works of arts drawn from the themes of “Heaven and Earth,” “Seasons,” and “Landscape,” and explores how each one exemplifies the Chinese philosophical concept of tian ren he yi (天人合一), unity or harmony between heaven, nature, and humanity.

1. Humanity is joined with heaven and earth

Figure 2: Tri-Ring symbolizing Heaven, Earth, and Humanity, Ming dynasty (1368–1644 CE), jade, nephrite, outer diameter 4 1/2 in. (11.75 cm). The Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney, Australia. Photo: The collection of National Palace Museum, Taipei.

Under the theme “Heaven and Earth” a jade object titled Tri-Ring symbolizing Heaven, Earth and Humanity (Fig. 2) presented the viewer with the ancient Chinese worldview of human/nature relationships. The three individual rings, representing heaven, earth, and humanity, are interlocked by a mortise and tenon joint, allowing each ring to rotate on its axis line. For instance, this tri-ring constructs a globe when unfolded and becomes three concentric rings when laid flat.

Curator Cao Yin explains that the inner ring represents heaven, as it is carved with the motif of the sun, clouds, and stars. The outer ring, decorated with mountains and oceans, represents the earth. The middle ring, depicting the motif of the dragon to symbolize emperors, represents the human world led by emperors.

The rotation of the tri-ring symbolizes the dynamics of energy flowing and exchanging among three powers of the universe. And the interlocked connection between three rings implies the mutual restraint of power between heaven, earth, and humanity. The arrangement of three rings reflects the ancient Chinese belief that humans mediate between heaven and earth and are the central component of the ecosystem.

2. Humanity adapts to the changes of nature

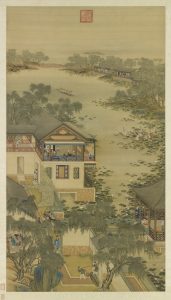

Figure 3: “The sixth month” from The Twelve Lunar Months, Qing dynasty (1644–1911 CE), hanging scroll, ink and paint on silk, 126 x 50 in. (320 × 127.6 cm). The Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney, Australia. Photo: The collection of National Palace Museum, Taipei.

Under the theme of “Seasons,” a scroll painting from the Qing dynasty displays how ancient Chinese people adapted themselves to June, one of the hottest months in the Northern Hemisphere (Fig. 3). Since animals prefer to hide in the shade to avoid the heat of June, this month was also called by ancient Chinese as fu yue (伏月, the month of hiding). Since June is also the season for the blossom of lotus flowers, he yue (荷月, the month of the lotus) was another name for June in ancient China. As the painting shows, people enjoy various recreational activities to reduce the heat, such as enjoying the breeze in a pavilion or going fishing and picking lotus flowers by riding boats on the pond.

Seasonality is a natural phenomenon that signifies the irresistible power of nature in regulating human lives. The ancient Chinese people believed that adapting to the change of seasons could result in a good harvest and personal health. In order to positively respond to nature, they divided twelve lunar months into twenty-four divisions of the solar year in their traditional calendar. Each solar term corresponds to relevant folk customs, including the timing of agricultural activities and recipes for seasonal food therapy. These cultural traditions emphasize the important role of nature in guiding everyday lives of human beings and suggest that people benefit from adapting to seasonal variation.

3. Nature is humanity’s spiritual homeland

Figure 4: Attributed to Wang Meng (1308–1385 CE), Fishing in Reclusion on a Flowering River, Yuan dynasty (1279–1368 CE), hanging scroll, ink on paper, 51 x 23 in. (129 × 58.3 cm). The Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney, Australia. Photo: The collection of National Palace Museum, Taipei.

Shan-Shui (山水, mountains and water) is a Chinese term for landscape. These two Chinese characters present the essence of the theme “Landscape” in this exhibition. In Chinese culture, mountains and water are not only the key components of natural landscape, but also the spiritual home for literati and recluses.

Liu Yinxing defines recluses as those politically exiled intellectuals living in times of war and regime change, who abandon themselves to the peace and tranquility of natural landscape. Wang Meng’s landscape painting (Fig. 4) portrays a recluse’s dreamland, in which he befriends the mountains and river. As pointed out by Liu Chengzhang, Wang Meng spent decades as a recluse. As a Han ethnic painter living in the Yuan dynasty ruled by Mongolians, Wang Meng possibly regarded himself as a political refugee and sought comforts and transcendence in nature, his spiritual homeland.

As the caption explains, the painting’s poetic imagery, such as chains of mountains, a river, peach blossoms, and a fisherman, were derived from The Peach Blossom Spring (桃花源记), a prose text written by the Six Dynasties recluse and poet Tao Yuanming. In keeping with Tao’s rendering of the ideal world, Wang Meng manifested the seamless fusion of human beings and nature by immersing the body of the human figure within the boundless beauty of nature. The relationship between the tiny human figures and the sublime landscape conveys the human being’s great reverence for nature and expresses Wang Meng’s (the reclusive painter’s) desire of being detached from the mundane world and returning to his spiritual homeland, nature.

In conclusion, the exhibition Heaven and Earth in Chinese Art: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei presented to a predominantly Western audience three main ways that ancient Chinese people pursued their harmonious relationship with nature: emphasizing that humans live in unison with nature, humans will thrive by responding to seasonal variation, and nature offers humans a spiritual home.