CAA News Today

CAA signs on to AHA statement condemning the “1776 Report”

posted by Allison Walters — February 01, 2021

CAA joins 41 other organizations in signing on to a statement by the American Historical Association (AHA) condemning the report from “The President’s Advisory 1776 Commission.” “Written hastily in one month after two desultory and tendentious ‘hearings,’” the AHA writes, “without any consultation with professional historians of the United States, the report fails to engage a rich and vibrant body of scholarship that has evolved over the last seven decades.”

The just –released “1776 Report” claims that common understanding of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution can unify all Americans in the love of country. The product of “The President’s Advisory 1776 Commission,” the report focuses on these founding documents in an apparent attempt to reject recent efforts to understand the multiple ways the institution of slavery shaped our nation’s history. The authors call for a form of government indoctrination of American students, and in the process elevate ignorance about the past to a civic virtue.

AHA Condemns Report of Advisory 1776 Commission (January 2021) | AHA (historians.org)

CAA signs on to ACLS statement on recent Kansas Board of Regents Actions

posted by Allison Walters — February 01, 2021

CAA, along with 23 other member societies, has signed on to a statement issued by the ACLS urging the Kansas Board of Regents to uphold employment protections for faculty.

The statement urges the Kansas Board of Regents to withdraw its endorsement of the proposed policy to ease the path to suspending, dismissing, or terminating employees, including tenured faculty members, without undertaking the processes of formally declaring a financial emergency.

It also calls attention to the statement co-signed in summer 2020 by leaders of cultural institutions and scholarly societies, including CAA, attesting to the importance of teaching and research to sustaining a robust economy and a just democracy.

Meet the Meiss Fund Recipients for Fall 2020

posted by Allison Walters — January 25, 2021

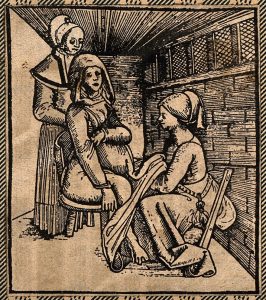

A woman seated on a obstetrical chair giving birth aided by a midwife who works beneath her skirts. Woodcut.

MEET THE GRANTEES

Twice a year, CAA awards grants through the Millard Meiss Publication Fund to support book-length scholarly manuscripts in the history of art, visual studies, and related subjects that have been accepted by a publisher on their merits, but cannot be published in the most desirable form without a subsidy.

Thanks to the generous bequest of the late Prof. Millard Meiss, CAA began awarding these publishing grants in 1975.

The Millard Meiss Publication Fund grantees for Fall 2020 are:

- Cammy Brothers, Giuliano da Sangallo and the Ruins of Rome, Princeton University Press

- Lindsay Caplan, Programmed Art: Freedom, Control, and Computation in 1960s Italy, University of Minnesota Press

- Margaret Graves and Alex Dika Seggerman, Making Modernity in the Islamic Mediterranean, Indiana University Press

- Diana Greenwald, Painting by Numbers: Data-Driven Histories of Nineteenth Century Art, Princeton University Press

- Subhashini Kaligotla, Shiva’s Waterfront Temples: Self and Space in Medieval India, Yale University Press

- Sigrid Lien, Colonial Legacies, Decolonial Activism: Indigenous Photographs Revisited, University of British Columbia Press

- Elizabeth Perrill, Burnished: Zulu Ceramics Between Rural and Urban South Africa , Indiana University Press

- Stephanie Sparling Williams, Speaking Out of Turn: Lorraine O’Grady and the Art of Language, University of California Press

- Rebecca Whiteley, Birth Figures: Early Modern Prints and the Pregnant Body, University of Chicago Press

Read a list of all recipients of the Millard Meiss Publication Fund from 1975 to the present. The list is alphabetized by author’s last name and includes book titles and publishers.

BACKGROUND

Books eligible for a Meiss grant must currently be under contract with a publisher and be on a subject in the arts or art history. The deadlines for the receipt of applications are March 15 and September 15 of each year. Please review the Application Guidelines and the Application Process, Schedule, and Checklist for complete instructions.

CONTACT

Questions? Please contact Cali Buckley, Grants and Special Programs Manager, at cbuckley@collegeart.org.

Art Journal Winter 2020 Video Abstract, “Now’s the Time,” a Message from Jordana Moore Saggese

posted by Allison Walters — January 13, 2021

Video Abstract – Now’s the Time from Taylor & Francis on Vimeo.

Art Journal Winter 2020

Usually when I sit down to write the introduction to a forthcoming issue of Art Journal, I am pleasantly surprised to find intrinsicconnections between the work we do as artists, historians, and critics. In past issues we have learned to look differently, to take matters personally, and to think in the present tense. And somehow we have done all this against an evolving (and often terrifying) backdrop of political, economic, social, environmental, and health crises. As I write this essay in early October, the pressure of reality—including the upcoming US presidential election—has made it difficult for many of us to orient ourselves to our research and creative practices. But, at the same time, the urgency of this work has never seemed more real.

In 2015 Toni Morrison wrote an essay for The Nation that, in part, framed her own feelings of helplessness in times of political and social turmoil. These days I find myself turning to these words again and again:

This is precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.

I know the world is bruised and bleeding, and though it is important not to ignore its pain, it is also critical to refuse to succumb to its malevolence. Like failure, chaos contains information that can lead to knowledge—even wisdom. Like art.

And so we must keep writing, making, and teaching. We must try to cultivate wisdom instead of succumbing to despair.

With Morrison’s mandate in mind I introduce this special edition of Art Journal: an issue centered on Blackness. The ideas represented here have been carefully brought into an intentional conversation around the experiences, expressions, and theorizations of Blackness. We have artist projects by two Black women—Allison Janae Hamilton and Chanell Stone—and all the book and exhibition reviews center on works by and about Black artists (thanks to the tireless effort of our reviews editor, Mechtild Widrich). The feature essays reorient our attention to artists—Mark Bradford, Samuel Levi Jones, Glenn Ligon, Howardena Pindell, Jack Whitten—who explore the histories, sensations, and consequences of Blackness in their work.

As argued so compellingly by Leigh Raiford in her essay, “Our work is to recognize how white supremacy functions as a way of seeing that any person of any race or positionally can work to undo.” I hope that in editing the first issue of Art Journal to focus exclusively on Blackness, I have provided a counterweight to the ideology of white supremacy that has infected our political landscape in the United States and (in so many ways) the history of art itself. As we mourn the murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd and the deaths of thousands from COVID-19, let us also work toward the new future and find meaning in the chaos.

– Jordana Moore Saggese

The entire issue of Art Journal Winter 2020 is free to read through March 31, 2021.

In Memoriam: Roland Reiss

posted by Allison Walters — January 12, 2021

Roland Reiss in front of by Unrepentant Flowers (April 2018), photo by Eric Minh Swenson

We are deeply saddened that Roland Reiss, whose practice spanned Abstract Expressionism, the plastic arts, and representational painting, died on December 13 in Los Angeles at the age of ninety-one.

Jorin Bossen has spoken on the life and career of Roland Reiss:

“Roland saw everything through the lens of art. Even in his last year he produced stacks of drawings each week examining the simple proposition of a circle positioned next to a square. This investigation of thought and possibility extended into the way that he undertook teaching. Teaching was an interactive process—an exchange of ideas. He knew how to point his students in the general direction we needed to be heading. Through new techniques, unfamiliar materials and mediums, seemly-unrelated exercises, and personal chats students often found ourselves in new and unexpected artistic territory. One that we didn’t know existed but filled us with hope, fear, and excitement. For Roland teaching was art.”

International News: The Van Abbemuseum in the Netherlands Explores the Legacies of Colonialism in a Solo Exhibition by Victor Sonna

posted by Allison Walters — January 08, 2021

The following article was written in response to a call for submissions by CAA’s International Committee. It is by Ilaria Jessie Obata, an art historian and curator currently completing an MA in Curating Art and Cultures at the University of Amsterdam.

Victor Sonna’s first solo exhibition, 1525, which opened at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven in July 2020, tells a multilayered story of personal introspection and shared colonial legacies. This collaboration between the artist and the museum is among the most recent exhibitions that fall under the mission scope of Musea Bekennen Kleur (Museums Confess Color), a contemporary platform established in Amsterdam in March 2020, in which “museums take accountability and responsibility through ongoing conversations about achieving diverse and inclusive institutional settings” (Musea Bekennen Kleur, https://museabekennenkleur.nl/).

The Van Abbemuseum, a participant in this project, is also one of the first museums in the Netherlands to embark upon a steady process of decolonizing its exhibitions and collections. This institutional decision was further marked by the Van Abbemuseum’s 2007 exhibition, Be(com)ing Dutch, in which participating artists Anette Kraus and Petra Bauer criticized racialized images of Zwarte Piet (Black Pete), which perpetuate the use of black face for the Sinterklass holiday (Saint Nicholas). The museum encountered severe backlash from the far-right party in the Netherlands for its criticism of the Dutch holiday, which further exposed this contested discussion within the country as whole. This response exemplified the need to continue the process of decolonizing cultural and educational platforms that perpetuate racial stereotyping. Therefore, Sonna’s solo exhibition builds upon the museum’s desire for institutional accountability regarding the Netherland’s recent past and its involvement with the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Sonna and the Van Abbemuseum decided to organize an exhibition with a dynamic narrative that would prompt discussion about contemporary colonial legacies. Working together, Sonna, Van Abbe director Charles Esche, curator Steven ten Thije, and guest curator Hannah Vollam, designed and curated an exhibition that presented Sonna’s research from multiple perspectives.

Figure 1. Victor Sonna in his 1525 exhibition at the Van Abbemuseum, 2020. Photo: Ronald Smits

Born in 1977, Victor Sonna is a visual artist who moved to the Netherlands at age nineteen from Yaoundé, Cameroon. Having studied at the Design Academy in Eindhoven and then at the AKV | St. Joost in Den Bosch, Sonna is based in Eindhoven and works in various mediums. His Van Abbemuseum exhibition includes three installations of tapestries, prints, and audio-visual material. The exhibition narrative started with his purchase of a pair of chains that once belonged to an enslaved person in New Orleans. The number 152 was engraved on these chains and thus remains the focal point for the exhibition title, 1525 (Fig. 1). Sonna’s installations regularly refer to the commoditization of human life under slavery, or rather “…the treatment of persons as property or, in some kindred definitions, as objects… when the individual is stripped of his previous social identity and becomes a non-person, indeed an object and an actual or potential commodity” (Igor Kopytoff, “The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process,” in The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, p. 65). Sonna’s purchase led to his own research on the socio-historical impact of colonial exploitation, which constructed and perpetuated the commodification of human life for Western imperial profit.

His audio-visual works, which contextualize and document the slave trade in Ghana, are shown in six separate film installations in the exhibition. Sonna visually captured the external and internal space of Fort Elmina, a former slave trading post that was seized and consolidated by the Dutch in 1637. He documents remembrances of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, which have remained imprinted upon the walls of the fort and linger within the smell of the dungeons. The fort “plays a central role within the exhibition since the title,1525, also corresponds to the year marking the departure of the first slave ships from the West African coast to the Caribbean islands”(Harmen van Dijk, TrouwNL, 18 July 2020, translated from Dutch by the author). Sonna used this historical research to better understand the dehumanizing effects of the trans-Atlantic slave trade that turned enslaved African individuals into commodities, and led to a specific form of merchandising the colonial: distinguishing people as objects and as lesser than human.

Figure 2. Victor Sonna, Tower of Babel, 2020, Van Abbemuseum. Photo: Ronald Smits

The accompanying installations showcase Sonna’s training as a visual artist as he meshes together the mediums of sculpture, metalwork and tapestry through the jaw-dropping 82-foot-high steam beam tower, from which his framed tapestries hang within the inner spire of the museum. This massive installation, titled the Tower of Babel (Fig. 2), contains the 152 tapestries that require multi-angled viewings because both sides of the frames are packed with layers of overlapping materials, from glued cane sugar to metallic nails and coins. Sonna gathered 152 European Gobelins tapestries, made between the eighteenth and twentieth century, which comprise his series Bleach and Dust, Sugar and Rubber and Maps. However, Sonna wanted to deconstruct the singular perception of these tapestries as representing “the history and prosperity of Europe” (Harmen van Dijk, TrouwNL, 18 July 2020, translated from Dutch by the author), by exposing the forms of exploitative slave labor used to extract materials such as sugar and rubber, which are imbedded and glued onto the surface of the tapestry. On Sonna’s website he states that this series approaches the “layering and displaying of connected histories that have been etched, trapped and layered in the earth” (Victor Sonna, http://victorsonna.com/site/news.php ).

Sonna presses different sculptural materials into the tapestries, creating multiple reliefs on their surfaces (Figs. 3,4,5). He “traps” metallic objects: coins, metal chains, and nails along with Kente cloth from Ghana that has been rolled up and sewn into the tapestries, and granulated cane sugar glued around the edges. He purposefully imbeds these materials into the textural DNA of the tapestry and locks each object inside it. The reliefs pushing out of the tapestry juxtapose the Gobelins framed surface with the visual effects of these contrasting materials, making us look again. The materiality of such commodities is weighed down by the history of their production, one fueled by the violence and death that characterizes the slave trade and its plantations. The artist’s desire to etch and trap together seemingly disparate materials creates a correlation between a shared European history of colonial exploitation and the creation of racial difference.

Figures 3, 4, 5. Victor Sonna, 2020, Van Abbemuseum. Photo: Ronald Smits

Figure 6. Victor Sonna, Wall of Reconciliation, 2020, Van Abbemuseum. Photo: Ronald Smits

Lastly, a striking section of this exhibition required two visitors to stand in front of one another, separated by a series of fifty-two silkscreen frames titled the Wall of Reconciliation (Fig. 6). The term “reconciliation” connotes Sonna’s desire to ensure that the printed image reconciled two opposing views. Every silkscreen required a dark backdrop in order to see the printed image; it is only visible if two visitors are standing on opposites sides of the same screen. Thus, the two viewers on opposite sides see the same explicit images of violence that are part of a series of drawings depicting slavery in Suriname, a Dutch colony that gained independence only in 1975. In Figure 7, the image depicts a young boy holding a rake, signifying the effects of enforced labor during the formative years of a child’s life and how it can mold a perception of the self that is intrinsically tied to an object of labor. Henceforth, each of these installations emphasized Sonna’s desire to deconstruct a biased and unilateral frame of reference.

Figure 7. Victor Sonna, Wall of Reconciliation, 2020, Van Abbemuseum. Photo: Ronald Smits

1525, which has received acclaimed reviews in the Dutch press, is on display at the Van Abbemuseum until May 2021. Writers have collectively applauded the museum’s commitment to showcasing this stirring and historically fueled narrative. The Van Abbemuseum will continue to produce related public programming that is both accessible and reflective of its mission to highlight the legacies of Western colonialism in a Northern European context.

In Memoriam: Robert L. Herbert

posted by Allison Walters — December 22, 2020

Robert L. Herbert

We are saddened to learn of the passing of Robert L. Herbert, a visionary in art history and extraordinary teacher to many. He received CAA’s Distinguished Lifetime Achievement Award for Writing on Art in 2008. He passed December 17 of a stroke at 91.

Robert L. Herbert

In an extraordinary career spanning more than sixty years, Robert L. Herbert was remarkably consistent in a practice that has come to define the social history of art, which he described as “the moral and passionate … search for what paintings and drawings meant in the artists’ time.”1

As an undergraduate at Wesleyan University in the late 1940s and early 1950s, he was fascinated by the history of science, an interest that encouraged his study of color theory in his dissertation on the nineteenth-century French artist Georges Seurat, completed at Yale University under the direction of George Heard Hamilton in 1957. By that time, Herbert had already been inspired by the work of Meyer Schapiro, who encouraged his lifelong commitment to socialism as a framework for political and intellectual development. Proud of his roots in a working-class New England family, Herbert resisted the formalist bias of his training, although he readily acknowledges a debt to those who taught him to look carefully at works of art and to appreciate the importance of technique and pictorial structure. From the beginning he always insisted that “the stuff of ordinary daily life should enter into art history,” and made it his goal “to restore the flesh of real painters and their culture to the bones of style and form.”

A desire to balance respect for the artist’s distinctive modes of representation with a socially and historically grounded reading of subject matter was a salient feature of Herbert’s research, which focused, for example, not only on the color and facture of paintings by Seurat and other Neoimpressionist artists, but also on the distinctive subject matter and the politics of their art. Recognizing that the prevailing view of Seurat tended to privilege his large-scale paintings, Herbert trained attention on his drawings in a book published in 1963; yet he also continued to explore the meanings of Seurat’s paintings, organizing a major retrospective exhibition on the hundredth anniversary of the artist’s death in 1991 as well as another, Seurat and the Making of “La Grande Jatte,” that was devoted to his most celebrated painting in 2004. In fact, many of Herbert’s most innovative and important contributions to the history of art have been made in the context of exhibitions, which require careful attention to individual objects in addition to the presentation of a unifying conception of the whole. For his first foray into this genre of scholarship, the 1962 exhibition Barbizon Revisited, Herbert wrote a catalogue that won CAA’s Frank Jewett Mather Award and precipitated a renewed appreciation of the work and historical significance of mid-nineteenth-century landscape painters such as Corot, Millet, and Rousseau, among others. His ambition for the exhibition was expressed in terms that convey his dedication to a particular kind of art-historical practice: “The purely historical treatment of art is bloodless. The real heritage of Barbizon art is in the paintings, and their vitality must be experienced in our viscera. Otherwise works of art are documents to be assessed, catalogued, and filed away. But there is a proper use of history, namely, to prod us into discoveries which release our imagination and permit us to rise to the realm of true poesis. An historical evaluation of Barbizon art will only have value if it succeeds in doing just this.”

Just as the study of Seurat’s drawings prompted Herbert to look carefully at Millet’s drawings and other work in articles and exhibitions of the 1960s and 1970s, so Seurat’s paintings eventually led him to the work of Fernand Léger, whom he considers to be Seurat’s descendant and a great practitioner of the craft of painting. Thus although Herbert’s scholarly reputation is bound to his work on nineteenth-century French painters—he has written books on Monet and Renoir, a survey devoted to the leisure subjects of the Impressionists, as well as the publications mentioned above on Seurat, Millet, and the Barbizon School—he has also produced significant scholarship on early-twentieth-century modernism. His first contribution to that field was an edited volume of ten essays, Modern Artists on Art, published in 1964. This was followed twenty years later by a detailed study of the large, diverse collection of European and American modernist art from the Société Anonyme that Katherine Dreier had bequeathed to Yale at midcentury and that Herbert had explored for many years together with his students. Along the way, Herbert developed research he had undertaken as a graduate student into a book, published in 1972, on David’s Brutus and its political significance in the context of the French Revolution; his commitment to the social history of art was also evident in a volume of selected art criticism by John Ruskin that Herbert edited in 1964 and for which he wrote an eloquent introduction that provided a thoroughgoing reevaluation of Ruskin’s significance from a variety of perspectives, demonstrating his acute relevance to the social history of art that Herbert was in the process of articulating at the time.

It is impossible to summarize Herbert’s contributions to art history simply in terms of his scholarly production, impressive as that output has been. He has also been an inspiring teacher of undergraduate and graduate students, setting an example in countless ways that go well beyond his commitment to scrutinizing original works of art alongside archival resources of the most diverse kinds. In addition to imparting these indispensable staples of the trade, he maintained an extraordinary level of personal and professional engagement with his students, loyally supporting their ambitions and celebrating their achievements, whether large or small. Refusing to be impressed by conventional measures of status, in 1990 he acted on his commitment to feminism by relinquishing his position at Yale in order to join his wife, Eugenia Herbert—whom he has always described as his greatest intellectual companion—on the faculty of Mount Holyoke College.

As professor emeritus and living in South Hadley, Massachusetts, he discovered a passionate interest in the life and work of a mid-nineteenth-century female botanist and illustrator named Orra White Hitchcock. “I’ve taken the plunge,” Herbert has remarked, “into the world of American women’s diaries, into travel diaries, and into the history of geology and the natural sciences, embraced in the broader spectrum of American social and cultural history of the middle third of the nineteenth century. It’s a new world for me, and I have no regrets at giving up French art history!” Subsequently he turned to exploring the history of Mount Holyoke and curated several exhibitions with James Gehrt and Aaron Miller.

He died December 17 of a stroke at 91 and is survived by his wife of 67 years Eugenia (Fi); children, Tim, Rosie, and Cathy; their mates, Mara, John and Chris; six grandchildren, and a wealth of friends to whom he was immensely devoted as well.

Announcing the CAA 2021 Keynote Speaker: Skawennati

posted by Allison Walters — December 21, 2020

Skawennati as xox

We’re delighted to announce that the Keynote Speaker for the 109th CAA Annual Conference will be Skawennati, who will address the membership during Convocation.

Skawennati makes art that addresses history, the future, and change from her perspective as an urban Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) woman and as a cyberpunk avatar. Her early adoption of cyberspace as both a location and a medium for her practice has led to groundbreaking projects such as CyberPowWow and TimeTraveller™. She is best known for her machinimas—movies made in virtual environments—but she also produces still images, textiles and sculpture.

Her works have been presented in Europe, Oceania, China and across North America in exhibitions such as “Uchronia I What if?”, in the HyperPavilion at the 57th Venice Biennale; “Now? Now!” at the Biennale of the Americas; and “Looking Forward (L’Avenir)” at the Montreal Biennale. They are included in the collections of the National Gallery of Canada, the National Bank of Canada and the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, among others. She was honoured to receive the 2019 Salt Spring National Art Prize Jurors’ Choice Award and a 2020 Smithsonian Artist Research Fellow. Skawennati is represented by ELLEPHANT, and her work is viewable at skawennati.com.

Skawennati has been active in various communities. In the 80s she joined SAGE (Students Against Global Extermination) and the Quebec Native Women’s Association. In the 90s she co-founded Nation to Nation, a First Nations artist collective, while working in and with various Indigenous organizations and artist-run centres, including the Native Friendship Centre of Montreal and Oboro. In 2005, she co-founded Aboriginal Territories in Cyberspace (AbTeC), a research-creation network whose projects include the Skins workshops on Aboriginal Storytelling and Digital Media as well as the Initiative for Indigenous Futures. Throughout most of the teens, she volunteered extensively for her children’s elementary school, where she also initiated an Indigenous Awareness programme. In 2019, she co-founded centre d’art daphne, Tiohtià:ke/Mooniyang/Montreal’s first Indigenous artist-run centre.

Born in Kahnawà:ke Mohawk Territory, Skawennati belongs to the Turtle clan. She holds a BFA from Concordia University in Montreal, where she resides.

Convocation will be held on Wednesday, February 10, 2021, 4:30-6:00 pm EST. Access to Convocation requires free registration for “Free and Open Sessions” and is included in paid registration.

Finalists for the 2021 Morey and Barr Awards

posted by Allison Walters — December 16, 2020

CAA is pleased to announce the 2021 finalists for the Charles Rufus Morey Book Award and two Alfred H. Barr Jr. Awards. The winners of the three prizes, along with the recipients of other Awards for Distinction, will be announced in February 2021 and presented during Convocation in conjunction with CAA’s 109th Annual Conference, taking place on February 10-13, 2021.

2021 Charles Rufus Morey Book Award finalists

2021 Alfred H. Barr Jr. Award finalists

Louis Marchesano, ed., Käthe Kollwitz: Prints, Process, Politics, Getty Publications, 2020

2021 Alfred H. Barr Jr. Award for Smaller Museums, Libraries, Collections, and Exhibitions finalists

Andrea Rosen, Wood Gaylor and American Modernism, 1913-1936, Fleming Museum of Art, 2020

Jinah Kim and Todd Lewis, Dharma and Puṇya: Buddhist Ritual Art of Nepal, Brill, 2019

CWA Picks: December 2020

posted by Allison Walters — December 15, 2020

December CWA Picks

December Picks from the Committee on Women in the Arts celebrate a selection of events, exhibitions and calls for work and participation featuring feminist and womxn artists and addressing issues concerning social justice and ethics in intersectional and transnational perspectives.

Food Justice In Appalachia: Call For Content; An exhibit by WVU Libraries in partnership with the WVU Food Justice Lab and the WVU Center for Resilient Communities.

https://exhibits.lib.wvu.edu/gallery_foodjustice

The call (deadline on February 1st, 2021; exhibition launch in August 2021) invites submissions exploring concepts of food justice, food sovereignty and community food security. Selected works will be included in an exhibition, which focuses on ways in which the food system shapes landscapes, defines economic systems and informs cultural practices.

Curators Conversation: Curating the Digital — a Webinar hosted by Art Curator Grid and SALOON London on December 17th, 2020

https://www.eventbrite.pt/e/curators-conversation-curating-the-digital-tickets-129483736341

Curators Julia Greenway and Noelia Portela will be in conversation with SALOON London co-founder Mara-Johanna Kolmel to explore the online spheres and the digital realm in curatorial practices. SALOON London is a professional network for women in the arts with the objective of creating an open forum to exchange ideas, experiences and initiate collaborations.

Online exhibition accompanying On Transversality in Practice and Researchconference 9-11 December 2020, organised by PhD students from across the UK

https://ontransversality.wordpress.com/exhibition/

This exhibition presents the works of Maria Teresa Gavazzi, Emily Beaney, Stav B and Caio Amado Soares, and Niya B. who reflect on the issues addressed by the conference themes: interdisciplinarity, intersectionality and transnationalism in research praxis, from anti-racist, decolonial, feminist, and queer methodological perspectives.

Feminist Art Coalition (FAC)

https://feministartcoalition.org/

FAC, a platform for art projects informed by feminisms, encourages collaborations between arts institutions with the aim of promoting and advocating for social justice and structural change. A series of collaboratively conceived events and exhibitions planned for 2020 have been postponed to 2021 because of COVID-19 closures.

Our inheritance was left to us by no testament prelude exhibition to OnHannah Arendt: Eight Proposals for Exhibition; Richard Saulton Gallery, London

Richard Saulton Gallery launches its programme ‘On Hannah Arendt’ in January 2021 addressing the political philosopher’s 1968 publication Between Past and Future, in which Arendt questions the lost freedoms in the period post World War II and the threads of broken traditions. The group exhibition Our inheritance was left to us by no testament, a prelude to the launch, features the work of seven women artists from Eastern Europe, Alina Szapocznikow, Barbara Levittoux-Świderska, Renate Bertlmann, Běla Kolářová, Jagoda Buić, Jolanta Owidzka and Erna Rosenstein, that speak to possibilities in art without tradition.