CAA News Today

A Look at the PhD in Creativity at the University of the Arts, Philadelphia

posted by CAA — June 26, 2018

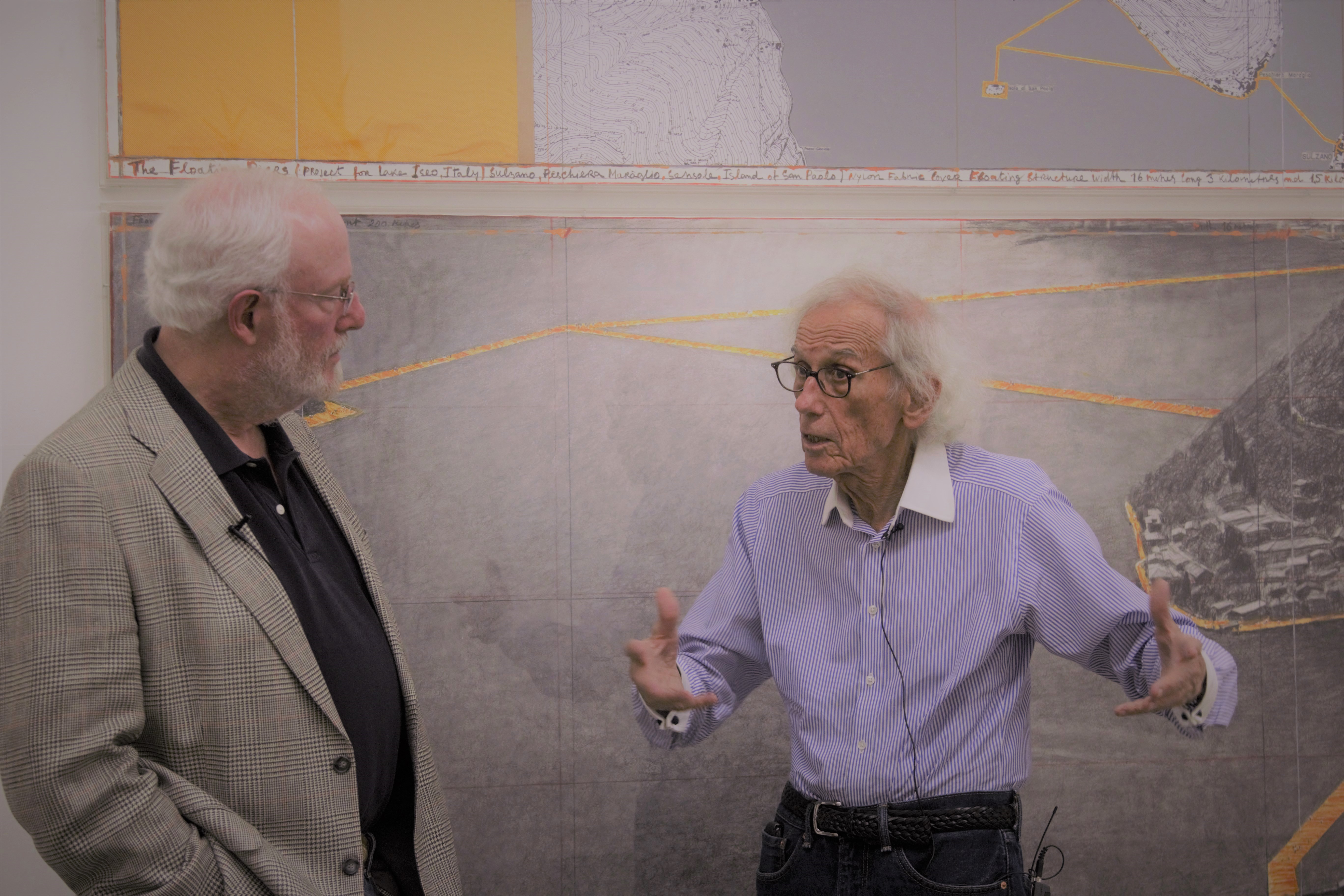

Jonathan Fineberg talking with Christo, a member of the advisory council and a model of the kind of creative thinking to which Fineberg hopes his students will aspire. Image courtesy Jonathan Fineberg.

Earlier this year, the University of the Arts in Philadelphia debuted a PhD program based on the premise that creative thinking lies at the heart of innovation in all fields. A low-residency degree for advanced interdisciplinary research in the arts, humanities, sciences, and social sciences, the PhD in Creativity seeks to fundamentally change the way students think about research problems. The program offers intensive immersion in creative thinking, cross-disciplinary workshops for dissertation development, and a bespoke dissertation committee tailored to best serve each student’s individual dissertation project. The first cohort of students are applying now to begin in the summer of 2019.

HOW DID IT COME ABOUT?

David Yager and Jonathan Fineberg met in 2015 at a conference on cross-disciplinary thinking in art and science sponsored by the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine (part of the National Academies Keck Futures Initiative). Well known for his pathfinding work in medicine and design, the academies had asked David Yager to serve on the steering committee. The organizers asked Jonathan Fineberg to speak about his new book Modern Art at the Border of Mind and Brain, which crosses psychoanalysis and neuroscience with art criticism for a fresh perspective on the nature of creative thinking. At this conference, Jonathan and David began a conversation that led to their collaboration in creating this radically reconceived PhD.

HOW DOES IT WORK?

The PhD in Creativity commences in mid-June each year with an intensive, two-week residency in a curated sequence of arts experiences interspersed with 4 days of methods seminars. Students also begin to workshop their individual PhD projects during this time with support from their cohort and from the Program Director.

The students meet again over a long weekend the following January, and again the following summer as they enter the final stages of research and begin writing in the second year. Most PhD programs commence with two or three years of training in methods and of mastery in the specialized knowledge of a discipline and then they administer a qualifying exam to determine if a student is ready to go on to the dissertation stage of the PhD. At University of the Arts, the PhD program looks at the MA-level training (done elsewhere), together with work experience, and a dissertation proposal as a kind of qualifying “exam” for admission and begins the program at the dissertation stage. The proposal must be interdisciplinary, preferably the kind of hybrid project that would not quite fit another PhD program. In the first summer, the cohort of peers from different fields and the program director critique each proposal in a workshop, set in the midst of a creativity immersion that attempts to break down the hierarchies of conventional training. Then a dissertation committee is formed around the needs of each student’s specific project, recruiting advisors from wherever the right advisors are to be found.

INTERVIEW WITH JONATHAN FINEBERG, Director of the PhD Program

CAA media and content manager Joelle Te Paske corresponded with program director Jonathan Fineberg earlier this year to hear his insights. Read their interview below.

JTP: Who do you see applying to the program? What is the sort of background/research would you like to see them coming in with?

JF: I’m already seeing, in the initial inquiries, exactly the kind of applicant I was hoping for: someone with a solid training in a field, and real experience putting their skills into practice, who then realizes they have an idea of how they might do things differently. I expect they will come with an MA, an MD, a law or business degree and have found a particular, hybrid project they’d like to explore for which they weren’t trained. I spoke with an extremely talented law school provost, for example, who is thinking about how the training of law school deans and presidents shapes the profession and I expect she’ll write an innovative book from this dissertation; a brilliant dancer with great performance experience came to me thinking about how dance companies are increasingly redefining themselves around discrete projects rather than continuing as companies and what that means both for the future of dance and for our culture more broadly; I spoke with a researcher at a drug company looking for a fresh angle on Alzheimer’s disease; and an experienced educator who is thinking about curricula for non-traditional learners. These kinds of projects will all be looking to a range of sometimes completely novel practices to infuse their investigations with fresh air.

JTP: The timeline of three years to completion is impressive.

JF: Both because these students are a little older and highly motivated and because the advising is carefully orchestrated and very hands-on, we expect the dissertations to move along more quickly than is often the case. Though in many programs you can complete the dissertation in three years after you finish the MA; it’s just that we effectively outsource the MA and ask for a little more real world work experience before you start.

JTP: The advisory council for the program is diverse in discipline – how did that come together?

JF: The people on my advisory council are all extraordinarily creative individuals who embody exactly what I hope my students aspire to as innovative researchers. So, these people serve both as inspiration and also as resources for great advice about how to build this program and where to find the right advisors for the students’ projects. Because I’ve had a long and varied career myself, I’ve encountered many remarkable people in a wide variety of fields whom I know well enough to ask for their thoughts.

JTP: How do you see the location of University of the Arts in Philadelphia informing the program?

JF: Although the program will take students in any field, it resides in an art school precisely because no one is better than artists at breaking down conventional thinking. If you’ve been well trained in a field it takes years to get over that training. It’s not a bad thing to be trained well, but we hope to instill more irreverence at the start.

JTP: The “curated sequence of arts experiences for an intense course in creativity” is very intriguing! What sort of arts experiences?

JF: Imagine yourself walking into a session of jazz drummers improvising and then having them hand you the sticks; you’d have to think fast and experiment to take over. That’s the kind of experience. Imagine hearing a major artist relive the thought process from which she or he generated a work or have a gifted theater director show you how to find a character within your own personality in the morning and then trying to create a performance for that character in front your group in the afternoon. Students will by and large have no tools for these kinds of experiences, forcing them to create a structure in their own heads to bring coherence to the experience. University of the Arts in particular has an array of talented artists who can create these sorts of simultaneous baffling and exciting experiences and because they will come one after another in a compressed time period the students will get faster at adapting and responding. This will also reinforce the effect of having really smart non-specialists cross question you about your project: you can’t use field jargon and you have to make sense. That will be happening in the workshops in the midst of the immersion course and the unusual methods readings.

JTP: What made you create this program?

JF: When I met David Yager, he was on his way to become the new President of the University of the Arts after having been a very successful dean at the University of California – Santa Cruz for some years. I had just retired from The Phillips Collection and the University of Illinois where I had been supervising PhDs for forty years. I was thinking about what to do next because I wanted to try something new in a new place just to mix things up for myself. In Modern Art at the Border of Mind and Brain I had attempted to make a scientifically grounded argument that we need works of art to develop our creative response to the world; I tried to show the evolutionary basis of art. That prompted David and I to start talking about how we could teach creativity in a PhD program to produce more creative researchers in whatever field they happened to be in. This is that program.

JTP: What would you say to naysayers of an expanded program like this one?

JF: This program is not for everyone. It’s great to be an outstanding practitioner in an established field. But for this, you have to have had the experience of coming up against the limits of your training, to feel that you have an idea that you weren’t prepared to deal with, and to believe you can create something really new. I’m excited to meet these new students!

How to Become an Art Editor: An Interview with Phil Freshman, President of Association of Art Editors

posted by CAA — June 12, 2018

Freshman’s home office. All photos courtesy Phil Freshman.

Phil Freshman is a freelance art editor and president of the Association of Art Editors (AAE). Formerly a staff editor at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (1980–84), the J. Paul Getty Museum (1985–88), the Walker Art Center (1988–94), and the Minnesota Historical Society Press (1995–99), he has worked on numerous books, exhibitions, and other projects, focusing mainly on art history, architecture, photography, and design.

We were curious what advice Phil might have for aspiring art editors. CAA media and content manager Joelle Te Paske spoke with him in April 2018.

Joelle Te Paske: I’m glad we have a chance to talk, especially to learn more about the Association of Art Editors and take a look at what you do.

Phil Freshman: When I talk to people about the AAE who didn’t know about it previously, they’re typically glad to know it exists.

JTP: It’s great. So, what are you working on nowadays?

PF: The last catalogue I edited was for the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, which recently took the “s” off its name and started calling itself “Mia.” Anyway, the book was about contemporary Japanese lacquer sculpture, and was tied to an exhibition that is on view now and will be up until late June. It’s a field of study I had never thought about much. You think of Japanese pottery, right? But you don’t think of pure sculpture. A very interesting and challenging project.

Right now, I’m editing a memoir by a lifelong friend who recently retired from the law. He spent a year hoofing it around West and East Africa in the early 1970s and thought he would get around to writing a memoir right afterward. Then 45 years went by like the wave of a hand, and here he is, doing it now. So, it’s a pleasure to help him, to know enough to make his manuscript better.

JTP: You’re learning a lot about him, I bet.

PF: I am. And that was a part of his life I hadn’t known much about to begin with.

JTP: How did you become an editor?

PF: I was a Los Angeles lad who first wanted to be a newspaper reporter. But despite trying for several years, it didn’t work out. I then lived for three uninterrupted years in Israel, Iran, East and West Africa, and Spain, finding ESL teaching jobs along the way. I came back home to get an ESL degree at UCLA. During that time, a friend in LA whose firm published books dealing with Western US history hired me part-time to review slush pile manuscripts and proofread book galleys.

A couple of years later, with just that little bit of experience but intrigued by the work, I applied for a copyeditor-proofreader job at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. I took the required test (along with something like 200 other applicants), was interviewed, and then hired. I thought, “Oh, God. Now I actually have to do something.”

JTP: Yes, now it was real!

Ralph Rapson: Sixty Years of Modern Design (1999). Freshman edited this and the other books illustrated here.

PF: At first, I had no idea what I was doing. But my senior editor was a great teacher. When he left the museum—too soon, alas—I was the only editor there. I worked on books about American painting and printmaking, 18th-century fashion, contemporary art, and more, plus the monthly members’ magazine, annual reports, lots of brochures, flyers, exhibition labels. It was full immersion and very long weeks until, after six months, I was allowed to hire somebody. Eventually, I had three editors.

JTP: That makes sense. Rather than just one, working at that scale.

PF: Right. But when I was hired from the Getty Museum to be the Walker Art Center’s first-ever editor, in 1988, I was once again a solo act—and remained one for three years. The Walker had an ambitious program of publishing catalogues and presenting exhibitions on the history of graphic design, Russian Constructivist art, contemporary sculpture, and this, and that, and the other thing! All that plus editing for the Walker’s very active film, performing arts, and PR departments. I worked 70 to 80 hours a week, and that didn’t stop even after I was finally able to hire an assistant editor.

JTP: There was no getting around the fact that you had to go through all that material.

PF: Right. Not just going through it all but also needing to be attuned to a constellation of details. That was, as it so often is, the job—the details, as well as panning out for the whole picture. And more often than not, I didn’t receive all the materials I needed at the get-go. Unfortunately, that’s all too typical in this racket. In fact, sometimes you get a little bit, and then some more dribbles in, then a bit more, and you have to assemble the material as it’s unfolding before you, make everything hang together. I had to develop a host of skills over the years, including diplomacy—at which I’ve never been adept.

Beyond all that, one reason I was initially attracted to editing was that I had no patience for formal schooling. I’ve found that editing has provided a rich, ongoing education in which I get a front-row seat to subjects about which I might otherwise never have learned a thing. Not to mention exposure to fascinating people, and to situations I wouldn’t have encountered if I weren’t doing this work. There are certainly things to hate about it, but the balance sheet works out in its favor.

JTP: It’s so detail-oriented, but you are committing your time to new projects and scholarship. It’s integral to the work.

Dining with the Washingtons: Historic Recipes, Entertaining, and Hospitality from Mount Vernon (2011).

PF: Yes. And I also keep coming back to this: you have to keep asking questions. One instinct that made me want to be a reporter applies perfectly to editing. I ask questions, and then ask more, and then ask some more. Often enough, I’ve had authors and curators who are responsive to that. The relationship works best when they understand that I’m on their side, trying cover any holes that open up because they were writing too fast. But some of them are resentful, insecure, brittle, and they can make that sort of thing difficult.

JTP: Yes, I can see it going both ways. I would think, though, that writers with more experience realize having a good editor can be like a good friend, someone who can make your work better before it goes out into the world.

PF: That’s it. I’ve worked with a few pretty well-known authors with whom it felt like a collaboration. They liked the back-and-forth. They didn’t just take all of my suggestions but said, “No, let’s discuss this further.” And then you get to a middle way that’s better than what you thought of, or than what they thought of.

JTP: Would you recommend that editors who are just starting out keep that in mind?

PF: Definitely. Another thing I like to tell aspiring editors is, “Go to the library.” You know, the library?

JTP: I’ve heard of those.

PF: [Laughs] Get hold of exhibition catalogues and other art books on a range of subjects, and then review all the separate essays or chapters, the footnotes and bibliographies, the plates, figure references, checklists, and the rest. And bear in mind, as you’re reading, that it’s highly unlikely that the original manuscript was delivered intact to the editor at beginning of the process. Probably dribbled in over a period of weeks, if not months.

You have to take the bits and pieces and make them fully consistent, factually accurate, grammatically correct, and maybe even interesting! So, I don’t know that someone has to have an art background per se in order to be an art editor. But I would say that having a feel for and a knowledge of language, a willingness to become genuinely invested in a subject, a good visual memory, and an insane attention to detail are all necessary.

JTP: I imagine AAE would be a great resource for people starting out. Where else should they look?

PF: LinkedIn is a good source. The old cold-call approach is not bad. Find people who work where you might want to work and contact them. I recently spoke with an editor friend who, though she had just quit Facebook, found a valuable online organization on it called Editors’ Association of Earth. She described it as a private, heavily moderated group and a place where you can engage with other editors, ask questions freely, and get advice.

JTP: Editors likely want to share their skills—many have devoted their careers to sharing knowledge, after all—and it seems like that would be good for people starting out.

PF: I’d also suggest getting immersed in The Chicago Manual of Style. And finding books about editing. Here are some I recommend:

- The Subversive Copy Editor, by Carol Fisher Saller. University of Chicago Press, 2009. Her monthly online Q & A, via the U of Chicago Press Website is terrific. Need to sign up for it.

- Exhibit Labels: An Interpretive Approach, by Beverly Serrell. Rowman and Littlefield, 2015 (second edition).

- Line by Line: How to Improve Your Own Writing, by Claire Kehrwald Cook. Houghton Mifflin, 1985. (This is the one I have, but there are probably subsequent editions.)

- On Writing Well, by William Zinsser. Collins, 2006 (30th anniversary edition).

- The Copyeditor’s Handbook: A Guide for Book Publishing and Corporate Communications, by Amy Einsohn. University of California Press, 2006 (second edition). A very good primer on the basics. It also includes copyediting exercises and answer keys.

JTP: That’s terrific. Thank you.

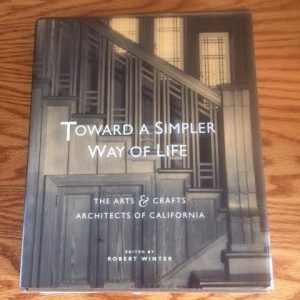

Toward a Simpler Way of Life: The Arts and Crafts Architects of California (1997).

PF: I’d also suggest that if a nearby college offers copyediting classes, take one. It can be very useful to learn the mechanics in a formal way. Such classes also help you see whether or not you have an appetite and instinct for editing.

JTP: This is important, too, because it’s an intensive practice.

PF: Right. Once you get involved in a job, it’s immersive. It is the writer’s book, the museum’s book, the publisher’s book, but you can’t ever say to yourself, “Well, it’s on them. I wash my hands of this,” or, “It’s not going to have my name on it.” You have to feel responsible for whatever project you’re on. In other words, you can’t say, “It’s just a job.”

Another thing to consider: Back in the days when I had stars in my eyes, I’d think, “How wonderful it would be to work for XXX Museum of Art. So prestigious.” But in fact, some of my best experiences have been with smaller institutions and some of my worst with larger, “important” ones.

JTP: That’s good to know.

PF: Usually, there are good people in such places. Sometimes a good attitude. Less bureaucracy. And often you can get things done more fluidly.

Another thing important to me is having solid relationships with graphic designers. I’ve worked with good ones and very bad ones. By good, I mean ones who like to share suggestions about what might work, ones who welcome it when you point out why a certain typeface, or size of type, or caption location in relation to pictures might be reconsidered. It’s a conversation. And then on the other hand, there’s the head-banging-against-the-wall experience of having to deal with the other kind of graphic designer. One of them referred to text as “texture,” something mostly useful as a visual complement to their brilliant layouts!

JTP: As an editor, I can only imagine [laughs]. Do you ever work in tandem with a graphic designer, presenting yourselves to a client as a team?

PF: Yes. Several designers I know will get a job and say to the client, “I know a good editor in Minneapolis. I’d like you to hire him.” By the same token, I’ll get a job and ask, “Do you have a designer for this?” If the client says no, I’ll offer contact information for three or four designers, making my top preference clear.

JTP: Good to know. Keeping track of the designers you like working with would help you establish a mutual-support system.

PF: That’s right. It helps you feel more comfortable going into a project—you know that you can kid around with the graphic designer, and that you can bitch about the client without worrying it’s going to get back to them.

JTP: Can you name a highlight of being president of AAE? Also, how long have you been president?

PF: I’m president for life [laughs].

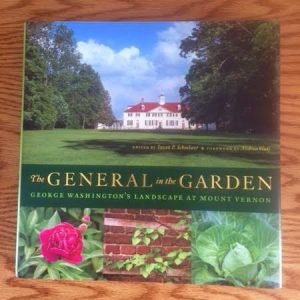

The General in the Garden: George Washington’s Landscape at Mount Vernon (2015).

JTP: [Laughs] Like a Supreme Court justice.

PF: You got it. I’ve occasionally had thoughts of not doing it anymore, but it’s not [too taxing]. Well, creating the first version of our soup-to-nuts style guide, in 2005 and 2006, which I did in tandem with three other editors whom I greatly respect—that did take months. But the result was just wonderful. I’m really proud of having done that. And I get lots of good feedback. Also, I like helping editors find work through the job opportunities page.

There’s also a section [on the AAE site] called Helpful Links. It has many sources you might want to refer to as you’re doing research for a book or an exhibition you’re editing.

The site is an open-source one. Anyone can use it freely. One AAE offering not visible on the site, however, is the rates survey we conduct every five years. It includes questions such as “How much do you charge for editing, proofreading, and other separate tasks?” And “Do you charge extra for working on weekends?” Among numerous others. We sort the answers, and provide a report with graphed percentages and selected verbatim responses.

JTP: That’s terrific. Sounds like it would help editors advocate for themselves.

PF: That’s the idea, of course. I don’t post rates-survey reports on the website because I don’t want potential clients, such as curators, browsing them and thinking, “Wow! Looks like I can get away with paying somebody $20 an hour!” But I’m happy to send the reports out to anybody who requests one.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

An Interview with Roberto Tejada, CAA’s New Vice President for Diversity and Inclusion

posted by CAA — June 05, 2018

Roberto Tejada

Last week, Roberto Tejada, CAA’s newly elected vice president for diversity and inclusion, talked with Hunter O’Hanian, CAA’s executive director, about the state of the field and why achieving true diversity is so difficult in the arts field.

The interview accompanies CAA’s newly created Values Statement on Diversity and Inclusion, adopted by the CAA board of directors in May 2018.

Hunter O’Hanian: You were elected as CAA’s first vice president for diversity and inclusion last October. Can you tell me why that position was created and what you hope to accomplish?

Roberto Tejada: Let me answer that first with a confession. I joined CAA as an emerging professional many years ago, newly positioned in academia, but not altogether of academia. I’d spent a decade of my formal and informal working years in the art and literary worlds of 1990s Mexico City. When I returned to the US, there were few art history PhD programs with faculty specializing in Latin American and US Latinx art; the art-related disciplines were not especially open or inclusive, and the CAA and its conference consistently felt to me like alienating spaces. So I was never much engaged as a member.

A few years ago, in 2013-2014, I had the opportunity to be in attendance at a CAA retreat held at Clark Art Institute, where I was a fellow. I listened to CAA’s leadership in discussions that led to the drafting of its current strategic plan; and I was impressed with the various commitments among its stakeholders to issues of advocacy and questions of diversity and inclusion. Those conversations inspired me to consider it was possible to effect change from within, so I agreed to put myself forward and was elected by the board in 2016 to serve as Secretary.

My understanding was that CAA’s membership had long sought leadership, whether on the board or staff, to embody, energize, and encourage a commitment to diversity and inclusion at every level of the organization. Under review were resolutions that resulted from the perseverance of CAA’s Committee on Diversity Practices, other subcommittees, and the efforts of many individual members, including the “Resolution to Create a New Officer with the Title of Vice President for Diversity and Inclusion” and the “Resolution Adopting a Values Statement on Diversity and Inclusion.”

Why was the position was created? It’s no secret that the membership of scholarly associations is in decline and that cultural institutions more broadly jeopardize their relevance and sustainability when they fail to make diversity and inclusion central to an organization’s structuring values. For the last decades, cultural life and fields of study have been categorically redefined by the art and scholarship of underrepresented groups; by artists and intellectuals of color, LGBT scholars, and others who have faced the challenges of institutional spaces, often without networks of support.

Also, insofar as the language of diversity and inclusion readily serves the neoliberal agenda, it’s conveniently adopted and used by universities and other organizations as a cover for actual equity in terms of race, ethnicity, skin color, and other social markers of difference, visible and invisible. The promotion of diversity and inclusion involves redressing an entanglement of past narratives but with a steady eye on the present and future. One way to view it, appropriate to art and design, is as a work-in-progress. CAA has been watchful of currents in higher education and the arts and it has led advocacy efforts of great impact for diversity and inclusion. If equity and inclusion were to become the priority issue for CAA and its membership, the human and intellectual vibrancy of our respective institutions could begin to more accurately reflect the plural narratives that have led to the composition of contemporary society. I’m passionate about the role that the board and membership can play to empower others, and so change the faces of CAA.

But in the context of current political discourses in the government and media, the challenge of advancing equity in the arts and humanities is to move beyond the model of appealing to hearts and minds, and to encourage policy-change guidelines that are concrete channels to access.

HO: What particular issues do you see in the fields of art history and visual arts with regard to diversity, either in the academic world or museums? A high percentage of CAA’s members are white. Is there a reason for that?

RT: Despite the multicultural context of the so-called global turn, the fields of art history and the visual arts have not been particularly hospitable to persons deemed different. If you serve on enough admission and hiring committees at different kinds of institutions, you cannot ignore the implicit biases that continue to perpetuate a lack of equity. Although fields of research and curricula have adapted to account for plural histories, the bodies that make art and design, that care and write about practices, history, preservation, and display at universities and museums, are still overwhelmingly white. It’s challenging to recruit emerging professionals of color who feel underrepresented in CAA. Members within the organization, however, have effected change. For example, the US Latinx Art Forum (USLAF) is an affiliated society that was formed by CAA members, and it now includes around 300 artists, art historians, curators, and other art professionals. Its founders Adriana Zavala and Rose G. Salseda, responded to “ongoing marginalization of US Latinx art within the academy and specifically within both ‘American’ and ‘Latin American’ art history.” USLAF’s members advocate for scholarship at the intersections of Latinx, African-American, Asian-American and Indigenous art and art histories. Its efforts are positioned to inspire artists and scholars of color to join and participate in CAA.

HO: In May, the CAA board of directors passed its Values Statement on Diversity and Inclusion. Why this particular statement now?

RT: That statement was a collaborative effort that resulted from discussions first among members of the Committee for Diversity Practices; then among board members, who voted to pass the statement. The statement will strike many as belated. As a starting point, it has been retroactively amended to the Strategic Plan and will serve as a guiding frame of reference for all CAA initiatives and actions moving forward.

HO: What can practitioners/educators in the field do to help diversify their own departments or student cohorts?

RT: Flora Brooke Anthony, Chris Bennett, and Katherine Brion facilitated an excellent workshop at the last CAA Annual Conference in Los Angeles on the “disconnect between intention and practice” and on why faculty hiring guides and administrative initiatives have been unsuccessful at creating diverse departments. Some of the short answers have to do with the professional pipeline, implicit bias, the comfort zone idea of “best fit,” and the social factors to do with accumulation of advantage and disadvantage. The long view requires challenging our membership to lend efforts and energies in the service of inclusion that actually enhances one’s research imagination at the departmental level and in the classroom. There are resources on CAA’s website: standards and guidelines for diversity practices, links to a database on multicultural teaching, digital resources with classroom ideas, archives of digitized imagery, and bibliographies of global visual culture. There are ways that practitioners and educators in art and art history departments can partner with units and other departments on campus whose faculty and graduate student research addresses the scope of human diversity and the structures of exclusion or discrimination. Departments can explore the possibility of creating residency fellowship for recent MFAs or PhDs who bring different embodied experiences. There are CAA-sponsored web platforms to be explored that could serve to link emerging professionals and graduate student to create an open space for questions and concerns relevant to faculty of color in departments unfamiliar with diversity needs. Department can actively recruit from diverse universities and community colleges, with an openness to candidates with experiences and expertise not always associated with the arts.

It’s important to remember as well that students and professionals of color at different stages of a career path often complain that so-called target opportunities are experienced and perceived as marginalizing, empty appeals to special treatment that once again delegitimizes the actual merits and recognition of excellence among underrepresented future scholars, designers, artists, curators and other museum professionals.

HO: Do you see movements, changes and trends on the national level that is making diversity work easier or more difficult?

RT: I think there is enough evidence to discern that the rhetoric fueling racial fears and resentment against minorities, enabled nationally and internationally by those in power, is inclined to have ripple effects in academia and in the arts. It has entitled attitudes and actions that have made the need to advocate for diversity and inclusion all the more urgent.

For more on CAA’s advocacy efforts, click here.

Click here to access the CAA Arts and Humanities Advocacy Toolkit.

Eileen MacAvery Kane and Herman Botes

posted by CAA — May 28, 2018

The weekly CAA Conversations Podcast continues the vibrant discussions initiated at our Annual Conference. Listen in each week as educators explore arts and pedagogy, tackling everything from the day-to-day grind to the big, universal questions of the field.

This week, Eileen MacAvery Kane and Herman Botes discuss ethics and graphic design.

Eileen MacAvery Kane is a full-time instructor in the Art Dept. at Rockland Community College in Suffern, NY as well as the author of Ethics: A Graphic Designer’s Field Guide and blog ethicsingraphicdesign.org.

Herman Botes serves as Head of the Department of Visual Communication at Tshwane University of Technology (TUT) in Pretoria, South Africa. He has a forthcoming co-authored book Educating Citizen Designers in South Africa, due out in 2018.

An Interview with Jim Hopfensperger, the New President of CAA

posted by CAA — May 24, 2018

Jim Hopfensperger at home.

As of this month, Jim Hopfensperger, professor of art at Western Michigan University’s Gwen Frostic School of Art, is CAA’s new president for the 2018-2022 term. As a professor and artist with a wealth of experience, we thought it would be a great opportunity to ask Jim his thoughts on CAA and the field at-large. CAA media and content manager Joelle Te Paske spoke with him earlier this month.

JTP: Hi Jim! Thanks so much for speaking with me. How are you?

JH: Very well, Joelle. Thank you so much for taking the time to visit!

JTP: To get us oriented, where did you grow up?

JH: My spouse, Jane, and I were raised in the upper Midwest. While career choices took us to Pennsylvania and Massachusetts, we returned “home” to Michigan eighteen years ago to be nearer aging family members.

JTP: And what did you study?

JH: I was educated as a craftsperson, working primarily in non-ferrous metals such as silver, gold, and copper. During a sabbatical leave from my faculty position at Penn State University in the early 1990s, I was presented the opportunity to work in a furniture studio in Massachusetts. Within a few weeks I was totally hooked, gifting my metal working tools to a younger artist and moving forward as a furniture maker.

Jim Hopfensperger, Shaker Purple, 2012

JTP: What drew you to the work you do now?

JH: I am drawn to how creating art/design objects—one-at-a-time and by hand—reinforces and reaffirms what it means to be a human being. Thinking with my hands, my eyes, and my mind to conceive well-designed and useful articles makes me feel whole. Perhaps I am a kinesthetic thinker/learner? It also seems possible that, for better and for worse, my sense of self is simply anchored in making things. The non-existent term “neuroceutical therapy” comes to mind!

JTP: What is exciting to you as the incoming CAA president?

JH: The forces of change are in motion all around us. It is a truly exhilarating time to be in the business of living!

As for CAA, a raft of research suggests that healthy organizations prosper when focusing efforts along two key pathways: 1) identifying and strengthening essential core competencies and 2) systematically exploring future capacities. This means sustaining CAA’s outstanding programs and services while simultaneously identifying the organization’s next purposes. Full attention to both matters seems essential if we are to extend a highly distinguished history of advocacy for artists, art historians, scholars, curators, critics, designers, collectors, and educators. I am grateful for this opportunity and excited about the work ahead.

Jim Hopfensperger, Deliberation No. 7, 2005

JTP: What work has been done over the past few years that you would like to build on? What would you like to see happening at CAA in the next year? How about in the next ten?

JH: Clearly, CAA remains an eminent learned society. At the same time it is increasingly fulfilling its potential as a professional association that serves members across educational, curatorial, scholarly, and creative pursuits. In the short term I am confident CAA will remain a strong association and identify more ways to support members in their professional lives.

Over the next few years a pivot toward some key constituencies might make strategic sense. Those include 1) the burgeoning ranks of contingent employees upon whom educational and cultural institutions have become increasingly reliant; 2) the large number of design and new/emerging media practitioners graduating from art and design programs; and 3) the community of international scholars, artists, and designers steadily advancing global perspectives. I look forward to working with CAA members, staff, board, and other stakeholders to map a future wherein these colleagues will be well served.

JTP: What has been a memorable professional moment for you at a CAA Annual Conference?

JH: I am deeply invested in the fellowship aspects of CAA. My fondest memory involves mentoring in the Professional Development Workshops at the Annual Conference in 2000. One my mentees was, as I, trained as a metalsmith. We worked closely after that conference to identify strategies for achieving his professional goals, and he eventually accepted a splendid academic position. In return for my service, and for each of the past eighteen years uninterrupted, he has gifted to me a handcrafted metal ornament to hang on our family holiday tree. Simply precious! (And if you are reading this Professor James Thurman, a wholehearted “Thank You!” is long overdue.)

Jim Hopfensperger, Deliberation No. 9, 2013

JTP: What would you say is the number one challenge facing higher education?

JH: Excellent question. My two cents: Adapting to the startling, inevitable pace of cultural and technological change is an operational necessity. Yet, communicating the value of an educated populace appears to be our most immediate and pressing challenge. Making the case for the causal relationship between educational opportunities and the ascendance of an increasingly ethical, moral, and empathetic society is job one. In the absence of such a mission statement, it is not difficult to imagine financial or economic ‘values’ easily filling the void.

The logical outcome might then resemble Oscar Wilde’s timeless quip about a cynic being ‘a man who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing.’

JTP: Do you have a favorite artwork?

JH: I have a keen interest in all forms of applied design—dynamic and surprising buildings, objects, communications, products, and processes. However, and for reasons I am not fully able to explain, my favorite artwork is Monet’s Four Trees in the Met’s collection. This quiet little companion and I visit perhaps once every 12 to 24 months. Invariably, I leave our encounters refreshed and restored.

Claude Monet, The Four Trees, 1891, oil on canvas, 32 1/4 x 32 1/8 in. (81.9 x 81.6 cm) Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image: Wikimedia Commons

JTP: What about a favorite book?

JH: Much of my reading over the past decade can be described as a search for serviceable maps of the human mind, followed by rubbernecking at accidents caused by irrational behaviors. Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking Fast and Slow is a fine example of the former, the type of mind mapping I find highly addictive. Kahneman’s lenses for understanding our extraordinary capabilities, while simultaneously identifying those pesky faults and deep biases that accompany human thought and action, help structure my own thinking. In a related way writings on decision-making in everyday life are equally intriguing and useful. Charles Duhiggs’s The Power of Habit, Dan Ariely’s Predictably Irrational, Keith Payne’s The Broken Ladder successfully illustrate complexities and contradictions when/where supposedly rational thoughts and human actions intersect, often to hilarious and/or tragic effect—endlessly fascinating stuff!

Jim Hopfensperger is a professor of art at Western Michigan University’s Gwen Frostic School of Art where he teaches foundation art. Jim’s art works have been shown nationally and internationally in over 100 exhibitions at venues including the Detroit Institute of Arts, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Auckland Memorial Museum, Lever House, University of Iowa Museum of Art, University of Oregon Museum of Art, State Museum of Pennsylvania, North Carolina Museum of History, and National Ornamental Metals Museum.

Jim’s past appointments include serving as Senior Associate Dean in the College of Fine Arts at Western Michigan University, Chair of the Department of Art & Art History at Michigan State University, and Head of the Studio Art Program at The Pennsylvania State University. He has also taught at the Massachusetts College of Art, University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth, Skidmore College, University of Michigan, and North Carolina State University.

Jim is Past President of the National Council of Arts Administrators, and is an accreditation visitor for the National Association of Schools of Art and Design. He earned a MFA from University of Michigan, a MA from University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and a BA from Michigan State University.

Kevin Curry and Christopher McNulty

posted by CAA — May 21, 2018

The weekly CAA Conversations Podcast continues the vibrant discussions initiated at our Annual Conference. Listen in each week as educators explore arts and pedagogy, tackling everything from the day-to-day grind to the big, universal questions of the field.

This week, Kevin Curry and Christopher McNulty discuss the challenges and benefits of digital technology in 3D/Sculpture.

Kevin Curry is an Associate Teaching Professor at Florida State University where he teaches digital foundations and sculpture. He’s currently in London teaching a photo for non-majors class.

Christopher McNulty is Professor of Art in the Department of Art & Art History at Auburn University in Alabama and teaches sculpture to undergraduates at all levels. He is a dual citizen of France and the United States.

Robert Howsare and Zach Fitchner

posted by CAA — May 14, 2018

The weekly CAA Conversations Podcast continues the vibrant discussions initiated at our Annual Conference. Listen in each week as educators explore arts and pedagogy, tackling everything from the day-to-day grind to the big, universal questions of the field.

This week, Robert Howsare and Zach Fitchner discuss teaching printmaking.

Robert Howsare is an Assistant Professor of Art teaching printmaking and foundation courses at West Virginia Wesleyan College.

Zach Fitchner is a printmaking artist and Assistant Professor of Art at West Virginia State University.

Joelle Dietrick and Meg Mitchell

posted by CAA — May 07, 2018

The weekly CAA Conversations Podcast continues the vibrant discussions initiated at our Annual Conference. Listen in each week as educators explore arts and pedagogy, tackling everything from the day-to-day grind to the big, universal questions of the field.

This week, Joelle Dietrick and Meg Mitchell discuss teaching new media.

Joelle Dietrick is a MacDowell fellow and Fulbright scholar who makes large temporary paintings, animations and games about global trade and human logistics. She’s an Assistant Professor of Art and Digital Studies at Davidson College outside of Charlotte, North Carolina.

Meg Mitchell is an Associate Professor of Digital Media/Foundations at University of Wisconsin-Madison teaching courses on digital foundations, interactive art, code based art and digital fabrication.

Alessandra Sulpy and Danielle Head

posted by CAA — April 30, 2018

The weekly CAA Conversations Podcast continues the vibrant discussions initiated at our Annual Conference. Listen in each week as educators explore arts and pedagogy, tackling everything from the day-to-day grind to the big, universal questions of the field.

This week, Alessandra Sulpy and Danielle Head discuss the crossover between Photo & Painting/Drawing.

Alessandra Sulpy is a graduate of the Maryland Institute College of Art and Indiana University, and this fall is beginning her 7th year of teaching drawing and painting at her new job at Winona State University.

Danielle Head received her BA in Film, Photography and Video from Hampshire College in 2007, and her MFA in Photography from Indiana University in 2011. She is currently Assistant Professor of Photography at Washburn University in Topeka, Kansas. Her teaching focuses on bridging together analog and digital media in the photography classroom and emphasizes photography as a conceptual and fine art medium.

Jonathan Johnson and Takeshi Moro

posted by CAA — April 23, 2018

The weekly CAA Conversations Podcast continues the vibrant discussions initiated at our Annual Conference. Listen in each week as educators explore arts and pedagogy, tackling everything from the day-to-day grind to the big, universal questions of the field.

This week, Jonathan Johnson and Takeshi Moro discuss teaching photo.

Jonathan Johnson is an Associate Professor of Photography and Integrated Digital Media at Otterbein University in Ohio and as worked in public affairs and the music industry prior to academia.

Takeshi Moro is an Assistant Professor at Santa Clara University, teaching digital and analog photography. Interesting fact: he is a former corporate finance banker and sushi chef.