CAA News Today

An Interview with 2018 CAA Distinguished Artist Awardee Pepón Osorio

posted by CAA — February 06, 2018

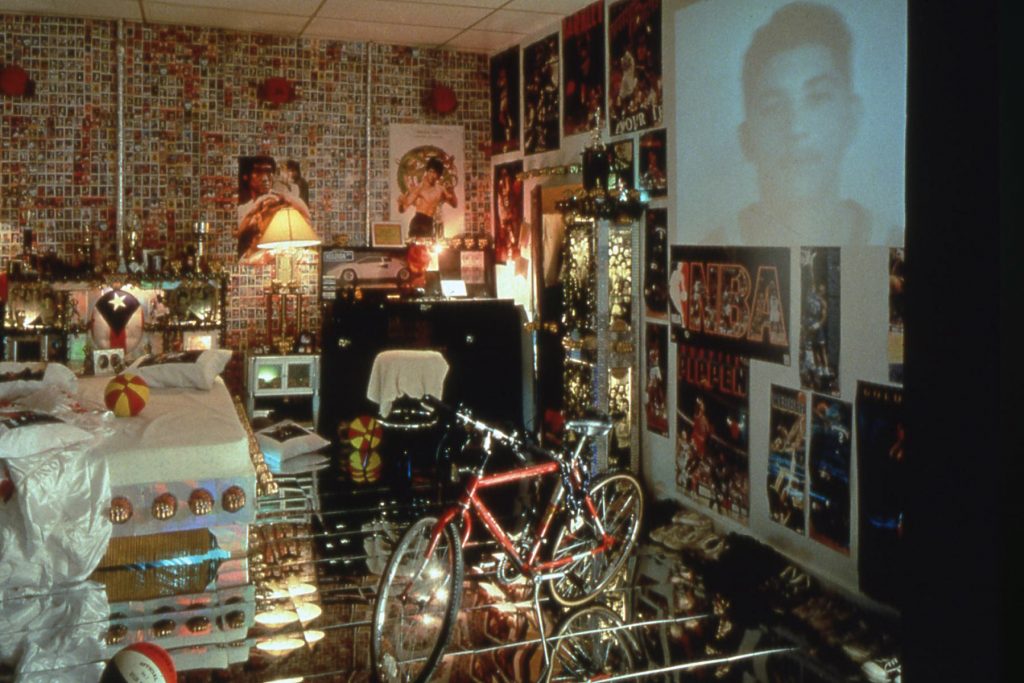

Pepón Osorio, Badge of Honor, 1995. Photo: Sarah Welles

Drawing on his childhood in Puerto Rico and his adult life as a social worker in the Bronx, artist Pepón Osorio creates meticulous installations incorporating the memories, experiences, and cultural and religious iconography of Latino communities and family dynamics. The 2018 CAA Distinguished Artist Awardee for Lifetime Achievement, Osorio is a professor in the Community Arts Practices Program at the Tyler School of Art at Temple University. He is also the recipient of a 2018 United States Artists Fellowship, among many other awards and fellowships.

CAA media and content manager Joelle Te Paske worked with Pepón in 2016 on reForm, a project responding to school closures in Philadelphia in collaboration with students, teachers, and Temple University. In the project high schoolers, affectionately nicknamed “Bobcats” after their former school mascot, were invited to contribute to an art installation at Tyler School of Art, where they also met with local politicians to advocate for community-based school reform.

Joelle caught up with Pepón in January 2018 to hear his thoughts on being an artist and professor, and to learn about his hopes for the year ahead.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

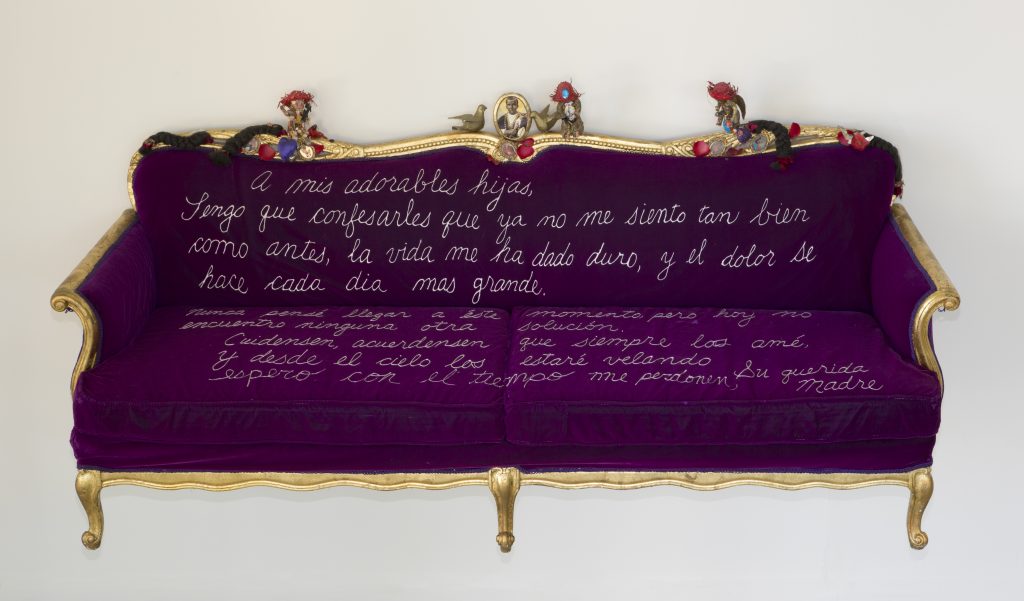

Pepón Osorio, To my darling daughters, 1990. Photo: Carlos Avedaños

JTP: I’m happy to be speaking with you. When I heard that you were getting the award, it was great news!

So, we find ourselves in 2018—how are you doing? What’s on your mind?

PO: I think that I am still processing the fact that we are in 2018 and 2017 didn’t look very good for us. Both as an artist and a citizen. I’m hoping that we begin to tell the truth in a country of lies. I hope that is what 2018 is like. This is a very interesting moment with the CAA lifetime achievement award, because I’ve been mostly thinking in retrospect. How in the world did we get here? How did we get here and how did this happen?

I’m looking in retrospect and trying to see where energy is stored and how to rejuvenate so I can move forward with a new perspective. That’s where I’m at.

JTP: I love that—looking for pockets of energy that are there, but haven’t quite been found.

PO: That in addition to how do we tell the truth in a country of lies? What does that mean? Everything’s been blurry to the point that you begin to doubt. That’s where we are.

JTP: Definitely. And what does your work look like right now?

PO: I am working on a couple of ideas. My production is very, very, very small. I don’t produce tons of work. I only produce work that I feel is urgent and is important. So I’m working on a whole bunch of ideas for possible pieces. Of all those ideas, one will emerge and come out. I’m working with that and also teaching. I’m trying to perfect the transformation of my methodology into a philosophical pedagogy. I’m trying to figure that out without losing touch with my creative self and my sense of curiosity.

JTP: When you say philosophical, do you mean putting together a formal pedagogy? Or more in a spiritual way?

PO: Well, both. I have been teaching at Tyler over the years and I feel that I always want to be able to center myself in my pedagogy in the way that I center myself in my artistic practice.

Pepón Osorio, Scene of the Crime… (whose crime?), 1993. Photo: Frank Gimpaya

I’m looking at what I’m really good at and that which I know most, which is my methodology of getting my work done, my practice. How do I transform that into a pedagogy of philosophy? That I can go around and teach something that I feel has this philosophy at the center of the work, similar to my artistic practice. Those are the things that I’ve been doing. A lot of looking in retrospect. Really looking in retrospect at the system.

JTP: That’s great. I’ve enjoyed being at CAA because I’ve been thinking more about history. It’s always there for you to learn from. The more you dig into it, the more you learn about the moment you’re in.

PO: Exactly.

JTP: What are the biggest changes you’ve seen in your time at Tyler as part of the faculty?

PO: The changes that I’m seeing at Tyler are new faculty members are coming in with a preoccupation that seems to be different from the history Tyler was built on. I’m looking at faculty members who are much more interested and preoccupied with things other than the object; where new faculty members are coming in with a clear understanding of what the true intention of becoming an artist is.

So I’m seeing that. I’m seeing transformations. We obviously have a new dean who is also looking at ways of transforming the past into a bright and hopeful future. Which is basically what I think this whole nation should be looking at.

JTP: I’m with you. Feels a little blurry, as you said, right now.

PO: Exactly. I think that the new blood and new faculty members that are coming to Tyler are interested in redefining a lot of concepts. I see that a lot in the world. I see that a lot with new generations of people coming up who are very interested in: “Let’s redefine this thing, because the system as it is simply doesn’t work.”

JTP: Would you say that’s your favorite part of being on the faculty at the moment?

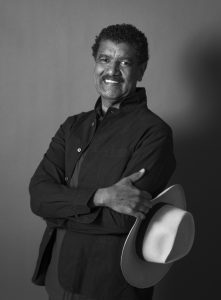

Pepón Osorio

PO: Yes. Also because I always feel that I found a niche in this. As an artist, dealing with the social, the political, the truth, and interdisciplinary work that creates very complex, chaotic environments—all that stuff seems to be so unacademic. I came in and I just felt like, “What in the world? What is my place in all this?” Little by little, by joining a new faculty and redefining, it’s making perfect sense. I’m finding myself more and more comfortable. That there are people around me that are supportive, that understand my trajectory and understand how I got to where I am now, whatever that place is.

It’s wonderful and I think to me that is a highlight. It’s finding a space in academia that feels comfortable and that I can bring the complexity of who I am into it, without necessarily having to be only one person.

JTP: I think that’s beautifully put. Everyone brings their own experiences. No one wants to be part of a monolithic institution that doesn’t let people be themselves …well, ok, some people do. But it’s interesting to me there’s so much more openness for that than I thought there might be, coming to a traditional academic membership organization like CAA, for instance.

PO: Basically, for me, it feels that this is not in demand. I am not filling up a demand of what all the people want to see. This is who I am. In relationship to the earlier question, I just feel like I was able to figure out a way to become myself in a world where people have demands of, “Oh you should be a professor.” Everybody thinks that you should be a [certain type of] professor. No. You just can’t be anybody else but who you are. It just so happened that being a professor is part of that.

We are looking at being an artist from a three-dimensional reality and in a more inter-dimensional way—that being an artist and professor is a very complex human being. I love that. I’d love to embrace that and not hide it from anyone. As a professor, I come in with all my imperfections as well. It’s not like I’m trying to correct them, I’m just going to do a balancing act with all this. That’s me, anyway.

JTP: If there was one thing that you would recommend to students or artists that they should be reading that they aren’t, what would you recommend?

PO: I’m not sure, but a student did ask me the other day if I have a recommendation of what he should be reading and what came out, which is really interesting, was feminist literature. Just listen to that stuff, read it, and understand what it means so then you can place yourself, as a male, in a place of understanding. That’s all.

JTP: I love it—you say, “Yes, I have an answer. Feminist literature.” Done.

Detail, En la barbería no se llora (No crying allowed in the barbershop),

1994. Photo: Frank Gimpaya

PO: I think that women should be reading it, but I think that men should be getting into it and reading and understanding where it comes from. I think that people, mostly men, will probably begin to empathize with the reality and the system, the fact that it’s not supportive of women.

JTP: I’m curious if you’ve attended CAA conferences in the past? What did you think?

PO: I have participated in the past. I have been in a couple of them.

JTP: It’s my first experience with the conference. It’s enormous.

PO: Yes, it always surprises me how the college system is much bigger than what I always think of it. I just wish that there were much younger people coming in to turn this thing upside down.

JTP: I agree. We’re trying to think of different ways to get closer to that. This year I know that we’re doing outreach to high schools in LA for all the free events. How amazing would it be to have a whole bunch of juniors and seniors in high school from a local public LA high school show up at the LA convention center alongside established, older academics? Just everybody.

PO: So both of them can see each other. Both of them can see each other and it’s like, “Okay, this is what’s coming up,” and the younger will say, “Oh, this is what it’s been.”

Find a happy medium somewhere in there. It’s just too much of the extremes. That’s my reaction. Too much of the extremes.

JTP: I agree. It reminds me of reForm, even just in terms of space—basically allowing people to feel comfortable. I just loved that the Bobcats (high school students who collaborated on the project with Osorio) walked through the main space of Tyler to get down to their classroom. It made Tyler theirs, in a way.

PO: A lot of people asked me, “Why aren’t you doing this piece in their neighborhood?” It was because the chances for the students to come into a college and to occupy space in a college environment were one in a million. I just thought if we can open up a space for them to occupy a classroom, open up a space for them to understand and to begin to look at the social architecture of a university, that’s more than enough for me.

I think that’s basically what I’m referring to when I’m talking about the CAA conference. If we can only suggest and show up a little bit more, that it’s much bigger than that, and that there’s a world out there both ways, that’s it. That’s what needs to happen. So people can come and begin to think differently. That was exactly what happened with the Bobcats. I said, “I’m just doing this at the institution because there are multiple functions in which the institution can work. This is one of them.” We think about institutions as the only place for education. Education is much bigger than that.

JTP: I agree, and I think that gets us closer to the truth you were talking about earlier. It opens up many more opportunities.

PO: Yes. It unties that sense of curiosity in all the kids’ minds.

reForm, 2014-2016, installation at Tyler School of Art classroom. Photo: Constance Mensh

JTP: Do you think artists can change the world?

PO: I think artists have changed the world. I think that the changes that I have seen in this country are not by artists alone, but I think that they have. When you’re talking about artists, I think you’re mentioning just these single artists changing the world, and I don’t think that that has happened. But I don’t think that that cannot happen.

I’m saying yes, because in the changes that I’ve seen in the world, there has always been an artist behind that. I do agree, but I don’t think that an artist alone can do it.

To break it down, I think that creativity has always been at the center of world’s change. Artists have always been on the periphery of it. Sometimes at the center of those changes.

JTP: Great, thank you. Lastly, you touched on this a bit, but what gives you hope for the future?

PO: Change.

JTP: Pepón, I’m right there with you. The possibility that it won’t be how it is right now.

PO: Exactly. That’s all. I just hope for change.

CAA’s Annual Conference Convocation, including the presentation of the Awards for Distinction, will occur February 21, 6:00-7:30 PM and will be livestreamed.

Elizabeth McFalls, Rae Goodwin, and Jane Jensen

posted by CAA — February 05, 2018

The weekly CAA Conversations Podcast continues the vibrant discussions initiated at our Annual Conference. Listen in each week as educators explore arts and pedagogy, tackling everything from the day-to-day grind to the big, universal questions of the field.

This week, Elizabeth McFalls, professor of art and foundations coordinator at Columbus State University and an associate vice president of programming of Integrative Teaching International; Rae Goodwin, associate professor in Art Studio at the University of Kentucky; and Dr. Jane Jensen, associate professor at the University of Kentucky, discuss teaching study abroad courses.

Bobby Tso and Andrew Casto

posted by CAA — January 29, 2018

The weekly CAA Conversations Podcast continues the vibrant discussions initiated at our Annual Conference. Listen in each week as educators explore arts and pedagogy, tackling everything from the day-to-day grind to the big, universal questions of the field.

This week, Bobby Tso, assistant professor of Fine Art at Northwest Missouri State University, and Andrew Casto, head of Ceramics at the University of Iowa, discuss teaching Contemporary Craft – Materiality and Concept in Ceramics.

Elliott King and Abigail Susik

posted by CAA — January 22, 2018

The weekly CAA Conversations Podcast continues the vibrant discussions initiated at our Annual Conference. Listen in each week as educators explore arts and pedagogy, tackling everything from the day-to-day grind to the big, universal questions of the field.

This week, Elliott King, assistant professor of Art History at Washington and Lee University, and Abigail Susik, associate professor of Art History at Willamette University in Oregon, discuss teaching Surrealism.

An Interview with Andrea Iaroc, Founder and Executive Director of the CORAI Project

posted by CAA — January 18, 2018

Andrea Iaroc created the CORAI Project to help art historians, in particular those without the privileges to access professional networks and generous financial resources. For more than ten years, her passion for historical research, teaching, writing, and philanthropy have advanced her work in museums and other art institutions, and forwarded her understanding of non-profits and intentional community work. An iconographer at heart, her current independent research interests focus on cultural hybridity and identity art.

Joelle Te Paske, CAA media and content manager, spoke with Andrea to learn more about the work CORAI is doing, her thoughts on CAA, and fundraising for inclusive art history.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Andrea Iaroc: I’ve been a member of CAA since 2007. I see the way the organization has moved in the past years—it’s definitely a different direction.

Joelle Te Paske: Most definitely. That’s part of the reason why I’m here, too.

AI: It used to be a little bit more traditional. That’s one of the things I’m focused on—moving art history away from that traditional foundation, [which is] very ivory tower. It’s exclusive and I wanted to change that in founding the CORAI Project.

It was frustrating as a woman of color—but, I admit that I do have privilege. I don’t have college debt, but I saw friends in school sometimes struggle with simple things, such as professors asking us to go to a gallery, or buy a membership to CAA for instance. The question was always: “Okay, do I use this money to pay for my books for this class, or do I …?” It was this thought in the back of my head, and those things happen because art history has been a “girls with the pearls” academic field. We still have that image problem.

JTP: Yes. That’s the stereotype.

AI: When you’re trying to do fundraising for art history, a lot of people ask: “What exactly are you doing, are you going to save the world?” It’s not a practical STEM field, but we need to equalize it in reflection of current sociocultural changes. We need to amplify the voices that have not been heard because of European ethnocentrism and patriarchy. The way that we experience the world, the way we grow up, our background—all inform the way we interpret things. That is important for me.

In August 2016, I finally managed to realize the idea of creating something new [the CORAI Project]—getting a logo, a mission, values, and building up a board. We’re just over a year old. CORAI stands for Creating Opportunities for Representing Art History Inclusively. Our logo features a heliconia plant, a South American Heliconia Bihai (even though I was born in Brooklyn, NY my parents are Colombian). The foundation of the logo is very Greco-Roman, but the heliconia is breaking through that ionic capital, moving up and breaking through. Our logo is pretty much what we want to do.

From the CORAI website: The Greek Ionic order is studied in every art history 101 class. It is part of classic architecture and, to this day, is used in governmental and certain religious buildings. It very much represents the Western roots of the field, as well as the palm that opens up on the background. Both Romans and Greeks were fond of foliage to adorn their capitals. In the middle, however, is a South American heliconia shooting upwards – transcending the heavy and old marble foundation. Design by Bella Hall.

JTP: I love that.

AI: Yes, it’s time to break through and do different things. [CORAI Project] gives away springboard grants, small grants to give a little ‘push’, to art historians who identify as PoC, people of color, in the state of Washington. So far, our first grantee back in the spring of 2017 used her money to go to the Rubin Museum of Art so that she could use their collections to complete her thesis.

JTP: That’s terrific.

AI: She was studying thangka paintings of Tibet [Tibetan painting using ground mineral pigment on cotton or silk]. She was the only person in the University of Washington, Seattle, doing this which therefore will change the records of art history in the university because she’s only one of two students this year that are graduating with a focus on Chinese art history.

The person that received the grant in fall 2017 is going to invest it in Japanese translation to ensure her thesis is correct. Although she’s faced resistance to her art historical Japanese art focus, she’s following through. One of the things that happens is that professors who do not have experience in what they call “non-western” arts, question PoC’s methodologies, settings, and interpretations because a traditional art history is the only thing they know. You need to do what you want to do.

That’s what this is about, and it’s small. But we’re out there and hopefully we can inspire other art history organizations to break the mold.

JTP: That is wonderful work. What would you say is the most exciting part for you personally?

AI: The moment the grants are given away. I see their motivation and enthusiasm for what they want to do in school or independently to shake things up in art history. That’s the best part.

JTP: Yes, you see the changes they’re putting in place.

AI: Exactly, because it gives results. It’s something solid. If the only thing I do in this life is to change one person’s take on art history, which is also my career, then so be it. So far we’ve helped a couple of them.

JTP: I’m with you. It’s definitely slow, but it’s exciting to see those changes happen.

I’m curious, have you heard about the recent Ford Foundation and Walton Foundation initiative?

AI: Yes, I read about it.

JTP: What do you think about it?

AI: I thought that CAA made an interesting question [on Facebook] at the end, like, “Do you think it’s a little too late?”

JTP: That was me [laughs]. Six million dollars is a lot of money, but spread over 20 organizations over three years…

AI: Exactly. That’s one of the things that I struggle with—I mean we’re a community organization—and I have been told by several people, “Oh, just talk to so-and-so, they’ll give you the money.” But the problem is, they’re very powerful and they want to jump on the bandwagon of “diversity and inclusion” and so their name is going to be attached to this project, but do they really mean it? What have they done that maybe goes against the integrity of who I am and what my organization is? This is the case when big organizations move the right way, but what does that mean? For instance, does that mean that they’re going to get Walmart to diversify?

JTP: Or let their workers unionize?

AI: Right, exactly.

JTP: A friend of mine online made the point of: we’re looking at how to get women and people of color and LGBTQ folks into leadership positions—we’re not talking internships.

AI: It’s good that people are a little bit more critical about these things because to [the Walton family] six million, it’s really nothing. What is this really about?

JTP: Yes, and I think it can be both good and bad. But asking the question is really important.

AI: Exactly.

Andrea Iaroc. Courtesy CORAI Project.

JTP: Have you attended CAA conferences in the past? What did you think?

AI: Yes. In 2012 I attended the 100th conference in Los Angeles. It was a big deal.

Back then, I was just coming out of five years of research for my thesis on Jewish art, specifically iconography. I looked for a relevant session and when I went, the organizer said it had taken them 16 years to get CAA to have a session on Jewish art. That it took them 16 years was disappointing, but there we were.

There were talks already of having another Jewish session in 2013 and now I can see that things have changed. The way that the conferences look now five years later is different.

Back then I went to a Pre-Columbian session where you had all these folks who, yes, of course, are excellent at their research profession and uphold conservation and believe in the return of a lot of these items to their countries. But at the same time I felt, “Really, you couldn’t find one Latin American professor that could talk about this? Just one?” You have all these folks that are white American and Canadian and they’re telling you about your heritage—it feels really strange.

When you look at [the conference sessions] now, the layout in terms of the list of people who are talking and where they come from and the sessions—it’s much better.

JTP: That’s good to know. I’ve been involved with the organization for less time than a lot of its members, including you, so I’m always curious to ask people. I think energy apart from the conference is also really important, making sure that people feel supported not just when they’re in one place together.

AI: Exactly.

JTP: Do you have suggestions for organizations besides CORAI that people should be following?

AI: There’s Art History That. It’s run by two women (Karen J. Leader and Amy K. Hamlin) and sometimes they post their own writings. They gave us our first Facebook shout out for our first grant. They’re very supportive about anything that’s changing in art history, the paradigms, the way that we even talk about women sometimes. In 2017 when you go to an Art History 101 class, women are still muses, but we’re not the artists. We’re still not taken into account as having a genius, especially when we’re talking about classics. The way that we talk—that language needs to be changed.

There’s also Smarthistory. They are from New York and they offer free resources for art history.

Material Collective, you may have heard of it because it’s connected to Art History Teaching Resources. They’re both connected and even have this big group of medievalists who are trying to fight the white supremacist narrative.

A piece featured in Smarthistory’s “South America before European colonization” section. Hands up close (detail), Seated Female Poporo, c. 500 B.C.E. – 700 C.E. Early Quimbaya, tumbaga (gold alloy), Colombia © The Trustees of the British Museum. Courtesy Smarthistory.

JTP: Excellent, thanks! What is the focus of your own research? You’ve mentioned it, but just to reiterate.

AI: Jewish art and iconography was my original focus, but because of it I’ve switched to cultural hybridity art.

JTP: Oh, interesting.

AI: Cultural hybridity includes artists who, because of the way our world has different heritages, draw inspiration from their mixed background. For instance, I had been researching contemporary Jewish artists and I ran across a work from Maya Escobar, who is from Missouri. Her dad is from Guatemala, he’s of Mayan ancestry, and her mom is Jewish, Ashkenazi, and so she made a tallit, a Jewish prayer shawl, using Mayan weaving techniques. That fusion of tradition—I’m very interested in it.

JTP: Do you think artists and art historians can change the world?

AI: Because I think that everything is connected, I always say art history does not exist in a vacuum.

JTP: I agree.

AI: Everything that’s happening scientifically, economically—it’s reflected. You’re going to see it in 50 years when you look back at art, you’re going to see it. Can it change the world? It can help change the world because humanities play a crucial role. The humanities help you see the world in a different way. They help your critical thinking skills and help you read humans. It helps you build community.

Jenn Proctor and Jon Rattner

posted by CAA — January 15, 2018

The weekly CAA Conversations Podcast continues the vibrant discussions initiated at our Annual Conference. Listen in each week as educators explore arts and pedagogy, tackling everything from the day-to-day grind to the big, universal questions of the field.

This week, Jenn Proctor, filmmaker and associate professor in Journalism and Screen Studies at the University of Michigan-Dearborn, and Jonathan Rattner, filmmaker and assistant professor in the Cinema & Media Arts Program and the Art Department at Vanderbilt University, discuss teaching film and video production.

Kirsten Olds and Heather Vinson

posted by CAA — January 08, 2018

The weekly CAA Conversations Podcast continues the vibrant discussions initiated at our Annual Conference. Listen in each week as educators explore arts and pedagogy, tackling everything from the day-to-day grind to the big, universal questions of the field.

This week, Kirsten Olds, associate professor of Art History at University of Tulsa, and Heather Vinson, visiting professor of Art History at Kalamazoo College, discuss diversity and inclusion in art history curricula.

Ray Yeager and Katherine Barnes

posted by CAA — December 18, 2017

The weekly CAA Conversations Podcast continues the vibrant discussions initiated at our Annual Conference. Listen in each week as educators explore arts and pedagogy, tackling everything from the day-to-day grind to the big, universal questions of the field.

This week, Ray Yeager, associate professor of Art at the University of Charleston and Katherine Barnes, adjunct professor at Columbia College, discuss teaching art appreciation to non-majors.

An Interview with 2018 Keynote Speaker Charles Gaines

posted by CAA — December 13, 2017

CAA 2018 Annual Conference Keynote Speaker Charles Gaines is a Los Angeles-based artist whose complex grid-work and mapping pulls from conceptual art and the field of philosophy. His work is currently on view at ICA Miami, at Cornell Fine Arts Museum, at kurimanzutto in Mexico City, and he has an upcoming show at Galerie Max Hetzler in Berlin. CAA media and content manager, Joelle Te Paske spoke with Charles about what he’s working on, his teaching at CalArts and Los Angeles in 2017, and if artists can change the world.

CAA’s Annual Conference Convocation, including the keynote address and presentation of the Awards for Distinction, will occur February 21, 6:00-7:30PM and will be livestreamed.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

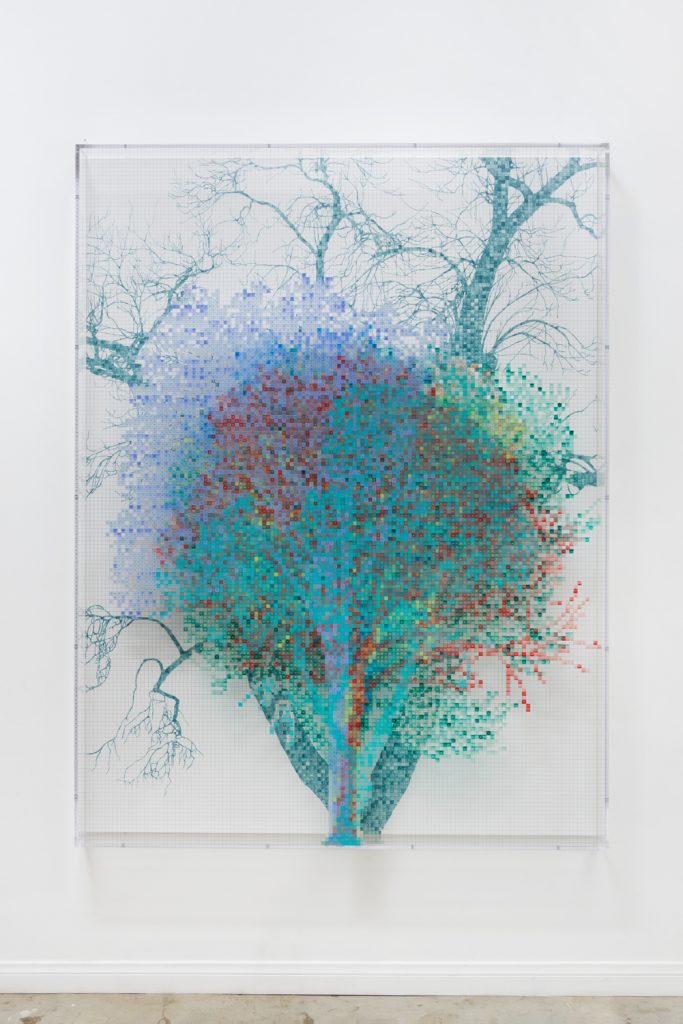

Charles Gaines, Numbers and Trees: Central Park Series 2, Tree #7, Maria, 2017. © Charles Gaines. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

Joelle Te Paske: I read the interview that you did for your Studio Museum exhibition in 2014 and you said: “I use systems in order to provoke the issues around representation.” I’m curious about how you’re thinking about systems right now in 2017.

Charles Gaines: I work with systems and structures, which results in the fact that the work itself is rule-based. My interest in it is really a suspicion about standard ideas of subjectivity. I felt that when I was in graduate school, the way we talked about art, seems that it was based on the assumption that the art object itself was a kind of access to the subjectivity of the artist. I got suspicious about [that] idea in modernism. That the purpose of art is, at its most essential core, a subjective practice, and if you take subjectivity out of it, you’ve eliminated or eviscerated the idea of art itself.

I wasn’t necessarily opposed to the concept of aesthetics itself, but again, when it became the principal and core purpose of a work of art, I had a lot of problems with that—to produce this aesthetic object—because that brings up issues of culture. And so, I was saying that aesthetic effects can be produced not by one’s intuition, but they can also be produced by rational strategies and intellectual, productive strategies, and one can have the aesthetic experience that’s a product of that. It’s a way of challenging the notion of how representation works in works of art.

JTP: It’s finding an alternative route into meaning, essentially. It gives you a different pathway.

CG: Yes.

JTP: Do you have a memory of first noticing a system—I’ve read that you’re interested in Buddhist teachings—that you hadn’t considered before?

CG: I was introduced to two books, one by Ajit Mookerjee which is called Tantra Art, and the other is Henri Focillon, The Life of Forms in Art. Buddhist works are interesting to me because the monks made works of art, but had no concept of the unconscious.

JTP: Interesting.

Charles Gaines. Photo: Katie Miller

CG: The personal subjectivity, they did not privilege that. But nevertheless, they have an art practice, made sculptures, drawings, and so it was interesting, because I had had to go outside the Western paradigm in order to discover that there are other ways of making work. And another thing that interested me about that is that the effect of that kind of process, this kind of sublime exhilarating experience, where you don’t actually have control over what you’re doing, because either the system has control of it or chance has control of it. And so you’re in this space that is to me way more interesting.

JTP: Yes, I’d say there’s a different kind of freedom to be found there.

If you could recommend one book to students or artists that they probably haven’t read, what would you recommend?

CG: Right now, books that deal with the postcolonial. Books that allow you to think about the relationship of art and culture, and the way that challenges assumptions of modernism. In my particular case, a very important book is Fred Moten’s [and Stefano Harney’s] The Undercommons, because of the way [Moten is] trying to negotiate what blackness means. It’s quite different from certain sociological or essentialist ideas of that subject.

JTP: Thinking about your role at CalArts, what are the changes that you’ve seen as part of the faculty?

CG: CalArts has managed to maintain, to some degree, the kind of reputation of an art practice that is not the standard. I was talking to some people about this the other day, and in particular Europeans generally think that CalArts is the most elite of art schools. They think that it’s among the best schools in the United States, but the reason why is because the school privileges ideas and challenges notions of certain standard practices. There’s a general suspicion of the idea of mastery.

JTP: That’s beautifully put.

CG: I mean, a lot of schools have developed programs or disciplines called new genres. So they’ll have painting, drawing, sculpture, printmaking, and the new genres. And so new genres is, I think, supposed to deal with the issues that are conceptually driven in works of art. You know, in particular, the avant-garde.

CalArts was invented with that kind of idea, and so I still think it’s a bit radical. Which blows me away actually, because I still get into discussions with other professionals, not so much in the art world, but certainly in academia, about whether the role of mastery informs curriculum. In our Masters program, we get the students who never really challenged the idea of mastery. In the 1970s, 80s, and 90s, there was the idea of art as an avant-garde practice; it wasn’t something that was controversial. It’s sort of a weird reversal of history, that the idea of art as an avant-garde practice is becoming more and more provocative. Particularly in the way people are thinking about educational systems and curriculum development and so forth. It’s the idea that they haven’t really come into the framework experienced in critiquing the idea of mastery with respect to works of art. I guess that’s the largest change that I’ve seen.

JTP: Yes, I think that your comment about the longer view of the history and the purpose of art is interesting, because history repeats itself and reconfigures itself.

When you’re working with students, what are you most excited about?

CG: In terms of what I enjoy in the experience of teaching at CalArts, we are lucky to get really good students. And the graduate students tend to be a little older and so, you wind up having the richest seminars—critical discussions about works of art, where the teaching goes two ways. I learn from them, they learn from me.

JTP: That’s terrific.

CG: You know, that keeps it quite vibrant and alive. There is a transition that the art students have to go through to get to that point where their criticality can reach a more sophisticated level. Their first year, [that] tends to be pretty traumatic for them. The dismantling of a lot of their assumptions about art. But through this process, they segue into the ability to be quite intelligent and quite interesting [in] the way they ultimately critique ideas and each other’s work.

Charles Gaines, Manifestos 2 (Installation), 2013. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Steven Probert © Charles Gaines. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

JTP: I’m curious too about LA. I know that you’re a longtime resident of the city—if you had to choose one thing for people coming to the conference, what you would recommend?

CG: LA has a remarkable list of museums, mostly contemporary art museums and modern art museums. Nobody should miss that. The art scene in LA is just generally interesting. I can also easily make a plug, because I’m on the board of the new ICA LA (Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles). People should make sure not to miss the ICA LA.

JTP: Thank you, that’s great. I know too that you’ve been part of the debate in Boyle Heights about art spaces and gentrification, and there’s been dialogue on all sides about it.

CG: I got caught up in the whirlwind of that. In this particular instance, the artists who’ve been moving into Boyle Heights in the last five or 10 years or so formed an alliance with a particular group of Latino artists to form a new strategy to fight gentrification. I was sort of upset by the fact that they’re attacking some very progressive alternative spaces.

In Boyle Heights, there’s a legitimate effort to fight gentrification that follows a history of certain strategies of fighting it that are unique to minority communities. In other words, Boyle Heights is a depressed community and was formed not because Latinos and Black people wanted to live there; it was formed because of redlining. And so those people, they want to stay in Boyle Heights, but they want it improved. And so their strategy against gentrification includes finding ways where they can increase their voices in terms of how this plays itself out. But this other group does not want any improvement. They just want to stop it.

They’re not interested in the idea of improvement, so what I said was that the artists who moved to Boyle Heights must recognize that they’re the first stage of gentrification. And I said that they were appropriating and colonizing the interests of the minority community.

JTP: You’re saying development could be good, it should be driven by the people who have been living there. They should have input and they should be guiding it.

CG: Whether it’s good or not, it’s inevitable.

JTP: It’s inevitable; okay that is a good distinction.

CG: There isn’t history where these kind of things, where gentrification was essentially stopped. What happened is that it was controlled.

JTP: We definitely want people coming from out of town to be aware of what is happening in Los Angeles. It’s helpful to hear your perspective, because you’ve lived there a long time and you’ve been active and involved, so thank you.

By the way, have you attended CAA conferences in the past?

CG: Absolutely. In fact, I’ve even been on a couple of panels. Several times in the past. There’s such a wide variety that’s available to see. I think it is very, very important to maintain that diversity and I have been noticing the increase in social and cultural issues.

Joelle: That’s definitely something we’re working on here at CAA.

I do have one more question, and it’s my favorite. Please feel free to answer it however you’d like. Do you think artists can change the world?

CG: I mean, it’s a cause and effect thing. Artists can change our ideas about art. But artists can also play a role in changing our ideas about society. They can play a role in that, like the activism that artists [did] in the 1970s helped to increase the number of women and minorities in art. And that comes from not only artists dealing with politics, but at the same time culture in general, a critique of male dominance and white male dominance, so artists play a role with other forms of social activism in changing things. It’s not like you can make a work of art and everybody’s just like “Oh, okay, I feel differently now.”

I think that people who make the argument that artists can’t change things—the phrase itself makes no sense to me. But the people who make that argument make it under the assumption—this is why Fred Moten’s The Undercommons is such an important book—of a simplistic notion about what politics is and how it works.

JTP: I agree. It’s my favorite question, because I very much believe that artists play a role in doing so.

This has been a rich discussion, thank you for taking the time. Is there anything else that you’d like to add in for people reading this?

CG: It’s a pleasure talking, and I’m looking forward to the event. I don’t know what I’m going to talk about yet, but I’ll think of something.

JTP: Yes, from this conversation, I have a feeling you definitely will.

Sarah G. Sharp and Kara Hearn

posted by CAA — December 11, 2017

The weekly CAA Conversations Podcast continues the vibrant discussions initiated at our Annual Conference. Listen in each week as educators explore arts and pedagogy, tackling everything from the day-to-day grind to the big, universal questions of the field.

This week, Sarah G. Sharp, assistant professor at University of Maryland and faculty of the Art Practice MFA Program at SVA in New York, and Kara Hearn, video artist and assistant chair of Film and Video at Pratt Institute, discuss video training for artists across disciplines.