CAA News Today

CAA Fair-Use Events in Los Angeles and Saint Louis

posted by CAA — May 19, 2017

A scene from the fair-use workshop at the UCLA Library (photograph by Sharon E. Farb)

On May 5, 2017, CAA hosted “Fair Use and the Visual Arts,” a presentation and panel discussion at the UCLA Library. The event was made possible by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Speakers on the panel included Peter Jaszi, the lead investigator on the CAA Code of Best Practices in Fair Use in the Visual Arts and Professor at American University Washington College of Law in the Program on Information Justice and Intellectual Property, and Janet Landay, Program Manager of the Fair Use Initiative at CAA. The pair, who have given presentations across the U.S. and internationally as part of the CAA Fair Use Initiative, talked about why it was important for CAA to undertake the project, their methodology, and the resulting Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts.

The second half of the event was devoted to a Q&A with the audience of approximately fifty-five people. Question topics ranged from addressing the issue of how the size at which an illustration is produced impacts fair use to indicating in a caption or illustration credits section that I am claiming fair use in the reproduction of an illustration.

A second discussion on CAA’s Fair Use Initiative took place at the American Alliance of Museum’s 2017 Annual Meeting and MuseumExpo in Saint Louis, Missouri. The panel discussion, titled “Copyrighted Material in the Museum: A Path to Fair Use,” took place on May 9. The panel brought together esteemed colleagues from the museum and publishing worlds and was comprised of Patricia Fidler, publisher of art and architecture at Yale University Press; Anne Collins Goodyear, codirector of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art; Judy Metro, editor in chief for the National Gallery of Art; and Joseph Newland, director of publishing for the Menil Collection. Hunter O’Hanian, CAA executive director, was the chair and moderator.

A presenter at AAM’s annual meeting discussed Andrea Wallace’s Still Life Pixel + Metadata Dress (photograph by Anne Young)

About seventy-five to one hundred people attended the standing-room only session and discussion revolved around fair-use issues for museums who want to use their own materials: catalogues, brochures, websites—even wall texts. A key takeaway from the session: museum representatives need to maintain good relations with donor and lenders, and getting approval from their own legal counsel, who tend to approach these matters with caution.

Later in the day Hunter O’Hanian spoke to faculty and students in the Department of Art History and Archaeology at Washington University in Saint Louis.

Learn more about the CAA Fair Use Initiative

Learn more about the 106th CAA Annual Conference in Los Angeles, February 21-24, 2018

CAA Goes to France

posted by CAA — May 08, 2017

The College Art Association has been invited to speak about its Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts at two conferences taking place in France in early June. On June 4 in Fontainebleau, executive director Hunter O’Hanian will participate in a session on “Fair Use and Open Content” at the seventh annual Festival of Art History, along with speakers from the Paul Mellon Center for Studies in British Art (UK), the J. Paul Getty Trust, and the French Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art.

The College Art Association has been invited to speak about its Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts at two conferences taking place in France in early June. On June 4 in Fontainebleau, executive director Hunter O’Hanian will participate in a session on “Fair Use and Open Content” at the seventh annual Festival of Art History, along with speakers from the Paul Mellon Center for Studies in British Art (UK), the J. Paul Getty Trust, and the French Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art.

Two days later, on June 6, Hunter will join Peter Jaszi, lead principal investigator on the Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts, in Paris to speak at a session on fair use during the annual conference of ICOM Europe. They will be joined by speakers from England, France, and Germany, to discuss “Copyright Flexibilities in the US and EU: How Fair Use and Other Flexibilities are Helping Museums to Fulfill their Mission.”

Both conferences provide opportunities for CAA to share its work on fair use with EU visual arts professionals. Though this feature of copyright law is virtually unique to the United States, there is increasing interest in Europe to provide greater access to copyrighted materials, especially in the cultural sectors of these countries. Travel costs for CAA’s participation are underwritten by a generous grant from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation.

Presentation on Fair Use at UCLA

posted by CAA — April 19, 2017

CAA is hosting “Fair Use and the Visual Arts,” a presentation and panel discussion led by Peter Jaszi, Professor, Washington College of Law, American University, on Friday, May 5, 2017. The event will focus on the College Art Association’s Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts and will take place at the UCLA Library from 10:00 AM to 2:00 PM. Lunch will be served.

Come join the conversation! Please RSVP to give us your lunch preferences, and when you do, please share your specific Fair Use questions so our presenters can break it down for you.

For more information: https://www.library.ucla.edu/events/code-best-practices-fair-use-visual-arts.

This event is made possible by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

CAA Presents a Fair Use Workshop in Richmond

posted by CAA — April 10, 2017

Peter Jaszi speaks to participants at a fair use workshop in Richmond, Virginia, March 24, 2017.

On Friday, March 24, the University of Richmond Museums, Virginia, hosted a CAA Fair Use Workshop, co-sponsored with the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts Statewide Program, and made possible with a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Elizabeth Schlatter, CAA Vice President for the Annual Conference, and Deputy Director and Curator of Exhibitions at the University of Richmond Museums, led the planning effort to bring over 40 artists, museum professionals, archivists, professors, librarians, and communications experts to the daylong workshop.

The program was led by Hunter O’Hanian, CAA’s Executive Director, and Peter Jaszi, Professor of Law at American University, and one of the two lead principal investigators on the project. After a round of introductions by attendees, Jaszi began the day with an introduction to the doctrine of fair use, followed by a presentation by O’Hanian about CAA’s four-year fair use initiative and the methodology employed to develop the Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts. The workshop continued with a focus on fair use in art museums, including when it can be invoked in exhibition projects, publishing, and online activities. During a working lunch, Jaszi and O’Hanian led discussions on reliance on fair use in teaching, publishing, and making art, and concluded the day with a discussion about fair use in libraries and archives.

Catherine G. OBrion, the Librarian-Archivist at the Virginia State Law Library, wrote afterwards, “I have a much better understanding of the legal standing of fair use, its intent, and how I can defend relying on it to my in-house counsel and others….One of the most useful workshops I’ve attended.” The workshop was followed by a reception at the University Museums for all CAA members in the local area.

CAA executive director O’Hanian also met with two University of Richmond classes the day before, one a museum studies seminar and the other a class on contemporary art and theory. The undergraduates benefited from O’Hanian’s advice on curating exhibitions, organizing public programs, surviving and thriving as a visual artist, and applying for artists’ residency programs.

Learning from Experience: Fair Use in Practice

posted by Janet Landay, Program Manager, Fair Use Initiative — March 14, 2017

We are eager to learn how individual CAA members are relying on fair use. Please take the following survey to let us know if, how, and to what extent you rely on fair use! Link here.

At last month’s Annual Conference, CAA’s Committee on Intellectual Property (CIP) organized “Learning from Experience: Fair Use in Practice,” a panel addressing fair use and how reliance on this aspect of copyright law has increased since CAA published its Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts two years ago. The CIP session featured leading visual arts professionals in four areas: the academic art library, publishing, art-making, and artist-endowed foundations, each of whom described the importance of fair use in her work. The session, which was attended by more than ninety conference-goers, was led by CIP’s new chair, Anne Collins Goodyear, co-director of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, and CAA president emerita, during whose tenure CAA undertook its fair use project, which culminated in the publication of the Code.

The panel opened with a brief overview of CAA’s fair use initiative by Goodyear, and then offered compelling examples of the Code’s application. Carole Ann Fabian, the Director of the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library at Columbia University reported that Columbia advances the principal of open access policy where possible, and that Avery librarians draw upon three fair use codes when advising library users about quoting from or reproducing copyrighted materials: that developed by the Association of Research Libraries (2012), CAA’s Code of Best Practices (2015), and the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) Guidelines (2016). The shared norms of the CAA and AAMD codes, both of which champion a liberal assertion of fair use, provide particularly helpful guidance on fair use applications related to copyrighted images. Avery is often the first point of contact for students and faculty who have questions about these issues, and as a collecting organization, is also a provider of primary content (and their digital surrogates) to scholars worldwide. Fabian noted that the work librarians perform educating users about copyrights and the doctrine of fair use is ongoing with each year’s influx of new students and faculty. Having a concise resource like CAA’s Code, makes it infinitely easier to introduce library users to this essential feature of American copyright law.

Victoria Hindley, Associate Acquisitions Editor, MIT Press, reported that discussions about fair use at last year’s CAA Annual Conference motivated her to work with her colleagues at MIT Press to pursue a fair use initiative of their own. With support from Executive Editor Roger Conover, Press Director Amy Brand, legal counsel, and others, Hindley helped to define a progressive position in support of responsible fair use. “One of our primary goals,” she said, “was to figure out how to reduce the burden of clearing permissions placed on the author.” The resulting proposal, which is undergoing final Institute approval, is a robust document that most notably, as she explained: “would no longer require authors to indemnify the press when they have made a reasonable good faith determination of fair use.” MIT Press has developed proposed new contract language in support of this position; and, to further empower authors, the Press has crafted permissions guidelines that take advantage of the CAA Code and also refer authors to it. “The CAA Code of Best Practices has proven to be an invaluable guide for us as we’ve held these discussions and made decisions about our own guidelines,” noted Hindley. The new policy pending adoption at MIT Press would provide protections similar to those that CAA grants contributors to its publications.

The third speaker was the distinguished artist Martha Rosler, who received a Lifetime Achievement Award during the conference from the Women’s Caucus for Art. Rosler has for decades incorporated into her work images circulating in what she has called the public sphere of mass media, including newspapers, magazines, and television, without stopping to consider copyright. While showing examples of her work, Rosler described the importance of processes like hers, which, she said, for many artists “constitute an essential form of critique.” Although Rosler’s practice predates the publication of CAA’s Code of Best Practices, she acknowledged that the Code serves to clarify the principles on which such a practice is based. She also noted that the Code has the potential to offer support and encouragement to other artists who might otherwise shy away from the legitimate use of copyrighted material in their work, for fear of adverse consequences. She also observed, with regret, that many artists, particularly those working in video, have deliberately abandoned or failed to undertake projects involving appropriation precisely because the legal departments of broadcast entities bar the airing of such works, out of fear of reprisal for purported infringements.

Francine Snyder, Director of Archives and Scholarship at the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, was the fourth speaker in the CIP session. She talked about the positive effect on the Foundation of a proactive fair use policy in the year since it was introduced. The main goal of the policy has been to foster scholarship about Rauschenberg, disseminate knowledge, and enhance educational initiatives. In this regard, Snyder reported, the policy has proven a great success, generating more scholarship and innovative projects. Among the outcomes to which she referred is an online gallery for children that includes images of Rauschenberg’s work. Snyder indicated that one of the most important values of the Foundation’s public turn to fair use has been to reduce anxiety on the part of those who want to reproduce the artist’s work for creative and scholarly purposes. Snyder mentioned that the fair use policy does not apply to commercial uses, for which the Foundation relies on licensing through VAGA. By way of conclusion, she explained that the Foundation is committed to an open dialogue as interpretations of fair use continue to evolve, as seen in the multiple applications of CAA’s Code of Best Practices.

Following the formal presentations, Jeffrey P. Cunard, CAA’s counsel, and Co-Chair of its Fair Use Task Force, moderated a discussion with the speakers and audience. Cunard noted the importance of the Rauschenberg Foundation’s turn to the doctrine of Fair Use in making work by Rauschenberg available for scholarly and creative purposes, and the relationship between fair use and an open approach to licensing images. He also clarified, in conversation with Rosler, that copyright holders had not objected to her pioneering work, which may not have been surprising, given the transformative nature of her use of appropriated material.

The talks by each of the speakers on this panel, along with the great interest expressed by the audience, point to increased awareness of the application of fair use since CAA published the Code of Best Practices two years ago. While detailing the many ways in which fair use is benefitting scholarship and creative practice, the session also makes clear the need for ongoing education about the Code, and the importance of publicizing and encouraging its use. We invite further examples of fair use in action, and any suggestions for the continued dissemination of the Code and the guidance it provides.

A CAA Road Trip

posted by Janet Landay, Program Manager, Fair Use Initiative — October 18, 2016

Bowdoin College Museum of Art in Brunswick, Maine (photograph by Janet Landay)

Bowdoin College Museum of Art in Brunswick, Maine (photograph by Janet Landay)In late September, Hunter O’Hanian and I had the pleasure of spending a weekend at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, to attend two CAA events hosted by Anne Goodyear, codirector of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art and a former CAA president. We arrived at the picturesque New England campus on a beautiful fall day. The college’s art museum, one of the oldest in the country, anchors the western edge of the quad, its neoclassical façade presiding gracefully over green lawns and majestic trees where students played Frisbee, read, or walked across campus. It was a perfect weekend to welcome CAA members to campus.

The first group arrived that Saturday afternoon to attend a CAA member reception, the first of several Hunter has planned around the country to provide an opportunity for him to meet with members in a relaxed setting and talk about CAA. The event began with a tour of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art given by Anne and her husband, the museum’s codirector, Frank Goodyear. Immediately following, we all walked a block away to Anne and Frank’s house to enjoy some wine and cheese on their back patio. The fifteen or so participants hailed from several schools and museums in addition to Bowdoin—Colby College, Bates College, the Portland Museum of Art, and the Farnsworth Art Museum—and included art historians, artists, librarians, and independent scholars.

Members spoke in turn about their most memorable CAA experiences: attending a first conference, interviewing and getting a job, meeting old friends, or networking with scholars in their fields. Hunter then shared thoughts about his goals for CAA based on what he has learned from members since he became executive director in July. He observed the importance of connectivity—how to keep CAA members in touch with issues in the field, but especially how to keep them in touch with each other. And he described many of the changes members will experience at the next Annual Conference, including a focus on personal experience, captured by a new theme for the meetings, myCAA.

On Sunday morning, several of the same CAA members returned, joined by others from around the state, for a half-day workshop about copyright and fair use. Peter Jaszi, a co–lead investigator on CAA’s Fair Use Initiative, came from Washington, DC, to Bowdoin to lead the program, which focused on how visual-arts professionals can use CAA’s Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts in their work. Following an introduction to copyright and fair use, the workshop began with a look at how museum professionals can use the Code when employing copyrighted materials in their work.

Participants had been asked to bring real-life questions with them. Thus, a museum director wanted to know whether his museum could allow photography in the galleries of works still protected by copyright. A curator described a challenge she had in getting an image for a catalogue from a museum in central China. When she received no reply from the museum, she resorted to scanning the image from another book. Is that fair use? Other questions involved loan forms, credit lines, and online projects.

As the day continued, the program moved on to address questions from professionals in other areas: librarians and archivists, professors and teachers, artists and independent scholars. Can a faculty member use images in class that she got from a flash drive she had received from a foreign museum? What kind of credit information is necessary for a blog about films? Is Shepard Fairey’s image of Obama a good case study for students learning about fair use? How should the institutional repository on a college campus view the copyright protection of yearbook photographs? By the end of the afternoon, a remarkable range of questions had been discussed, and the forty participants came away with a much greater understanding of fair use and how to rely on it in their work.

Peter Jaszi and Kyle Courtney at CAA’s fair-use town hall at Harvard University (photograph by Janet Landay)

Peter Jaszi and Kyle Courtney at CAA’s fair-use town hall at Harvard University (photograph by Janet Landay)On Monday, Hunter, Peter, and I were in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to join Kyle Courtney, a copyright specialist in Harvard’s Office for Scholarly Communication, for a fair-use town hall on the campus of Harvard University. As in Maine, Peter began the program with an introduction to fair use, and I followed with a description of CAA’s Fair Use Initiative. Kyle spoke about a program he directs at Harvard that trains librarians to be “first responders” to users’ questions about fair use. Although relatively new, the program has proven to be an effective way to support and teach visual-arts professionals about fair use. It is now being replicated on other university campuses. The event was then opened to questions from the sixty-five members of the audience, which Peter and Kyle discussed in depth.

Many of the topics were similar to those that had been addressed at the Bowdoin workshop, but a new subject emerged as well: advocacy. Does a professor who has had a manuscript accepted have any recourse when her publisher requires signed author agreements stating that all images had been cleared for publication and all fees paid? The answer is yes; she can ask her publisher to read CAA’s Code and explain that many, if not all, of her uses of images comply with the doctrine of fair use. While the effort may not succeed (though CAA has several success stories on file), over time it will familiarize publishers with the principles outlined in the Code. Changes have already taken place, in large part due to this kind of challenge from users. Yale University Press now accepts fair-use defenses from its authors who are publishing monographs; the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation embraced a fair use policy for that artist’s work; and CAA not only encourages its authors to consider whether or not their uses are fair, but it also indemnifies authors against lawsuits about works used under fair use.

The program concluded with a reminder that CAA is happy to answer questions about fair use; please don’t hesitate to contact us at nyoffice@collegeart.org.

The CAA member reception at Massachusetts College of Art and Design (photograph by Janet Landay)

The CAA member reception at Massachusetts College of Art and Design (photograph by Janet Landay)Later on Monday, Hunter and I joined another group of CAA members at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design for a wine-and-cheese reception at the school’s President’s Gallery and Bakalar and Paine Galleries. Attendees included a wide range of members, from professors who have belonged to the association for thirty years to new members just graduating from MFA programs. Lisa Tung, the gallery’s director and curator, kicked off the event with a tour of two exhibitions currently on view, Encircling the World: Contemporary Art, Science, and the Sublime and Women’s Rights Are Human Rights: International Posters on Gender-Based Inequality, Violence, and Discrimination. Hunter, who is a former vice president for development at MassArt, then invited participants to speak about how CAA is valuable to them. He emphasized the importance of hearing from members so that CAA can support them as fully as possible in this rapidly changing world.

CAA’s road trip continued in early October with another member’s reception in Portland, Oregon. Later this month we will convene a fair-use workshop in Seattle, Washington. More events are planned for early next year in Georgia and Virginia. Stay tuned!

The Bowdoin College fair-use event was organized by the Bowdoin College Museum of Art and CAA, with funds provided by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The Harvard University fair-use event was organized by Harvard’s Office for Scholarly Communication, thanks to the generous support of the Arcadia Fund, and by CAA, with funds provided by the Mellon Foundation.

A Fair Use Code Changes Practice in the Visual Arts: The Numbers

posted by CAA — August 04, 2016

How much difference has the release of the College Art Association’s Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts made so far? Even a few months after the release in February 2015, there was significant change in the field’s practice.

A survey of more than two thousand members of the College Art Association, starting seven months after the launch of the Code and winding up in January 2016, was analyzed by American University faculty and graduate students. Here’s what we know:

By and large, and as expected, patterns documented in a 2013 survey remained in place in the few months after the CAA Code was launched. The great majority of visual arts professionals still default to permissions, even though they have some experience of fair use when permissions processes fail. That choice is often costly. About a third of the respondents continue to report problems with avoiding projects, abandoning existing projects, and serious delays of more than three months, because of permissions.

But as well, we saw some real changes.

- The Code spurred a significant group of people to try fair use for the first time. Some 11% of those who have employed fair use did so for the first time after the Code came out.

- The Code spurred institutions to revise their policies. More than half—57%–of respondents who reported some institutional policy change said it had happened after the Code was released.

- Editors reported the largest amount of change, of any occupational group. This reflects the fact that several institutions publicly announced a change in policy, including the College Art Association. CAA’s author agreement now encourages a default to fair use where in line with the Code.

These changes, which occurred after only months of experience with the Code, happened because of widespread and networked knowledge.

o Two-thirds of respondents said they had heard of the Code before they took the survey.

o Most heard from multiple sources, but CAA was the most common source, whether through the conference, a newsletter or the website.

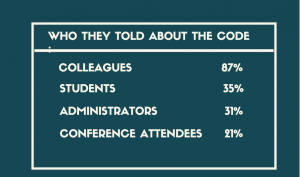

o A third of those who had heard about it had shared the news with someone else—a gesture that shows trust in the information, and confidence that it will be useful.

o Mid-career and veteran members of the field were much more likely to have heard about it than the newer entrants.

This is only the beginning, though. There’s still a lot to do.

- More than a fifth of respondents said they simply did not know whether fair use was valuable or not in their work. For a tool so fundamental to the functioning of the field, that is an alarming information gap.

- Only half of those who had heard about the Code went on to use it in the months after its release.

The survey results provide some next steps:

- Knowledge matters. The more confident and grounded respondents are in their understanding of fair use, the more likely they are to use it. So sharing your knowledge about the Code is crucial.

- Veteran leadership matters. Newer entrants to the field are less likely to have heard about the Code or to have experience with fair use.

- It’s worthwhile investing in the newest entrants. Although they were less familiar with the Code or fair use, they were the most likely to recognize that fair use is valuable to their work. They also are the most likely, they say, to change behavior with greater confidence in their knowledge.

- Institutions are really important in changing practices–to set terms, spread the word, and by publicly announcing their decisions to give confidence to others.

- Higher education is particularly important, especially for those, like artists, who may not be consistently working within institutions as they develop their careers. Universities, colleges, and art schools can educate the next generation about the new normal.

For more information about the Code, including informational videos, infographics, and frequently asked questions, visit the Fair Use page on the CAA website.

Originally published by the Center for Media and Social Impact in the School of Communication at American University.

Help Us Develop a Fair Use Curriculum!

posted by CAA — May 03, 2016

In 2015, the College Art Association published a Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts that established policies on the fair use of copyrighted materials for professionals in the visual arts field. The Code outlines the principles and limitations for applying the doctrine of fair use in five areas: critical writing, teaching, making art, museum uses, and online access to archives and special collections. It is available online, along with supplementary information, at the Fair Use web page.

With the input of our members, CAA is now developing curriculum materials to help teachers educate their students about fair use so that people entering the field will start out with a basic understanding of this important doctrine. Please help us develop useful materials by completing the following short survey, which is being administered by American University, CAA’s partner on the fair use initiative.

Please complete no later than May 20.

There are only six questions that should take less than five minutes to complete.

Thank you for your help!

Fair Use Is Up to Date in Kansas City

posted by Janet Landay, Program Manager, Fair Use Initiative — April 21, 2016

“Do we have to seek copyright permission to post on our website a scholarly checklist of twentieth-century paintings?” “Our museum wants to put an image of a contemporary sculpture from its collection on an invitation for a fundraiser. Do we need copyright permission?” These are the kinds of questions a group of art-museum professionals discussed at a half-day workshop on copyright and fair use sponsored by CAA with funds provided by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and held at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri, on April 8, 2016.

When Patricia McDonnell, director of the Wichita Art Museum, decided her museum could use input and guidance in applying the policies outlined in CAA’s Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts, she organized a meeting for art museums in her region, believing that the support and information she needed was likely the same as her neighboring colleagues. As a member of CAA’s Task Force on Fair Use, McDonnell was familiar with the approach outlined in the Code, and her primary goal was to design an event that would generate immediate practical results. To that end, the “fair use summit” featured two elements that made it particularly effective. First, each of the eight participating museums was represented by its director, legal counsel, and staff member responsible for rights and reproduction. Second, each museum submitted a case study of a fair-use issue from their institution in advance, thereby providing practical examples for consideration during the workshop. As a result, the pragmatic discussions that took place exemplified the type of analysis necessary to determine on a case-by-case basis if the use of a copyrighted text or image is fair; the talks also unified the participating staffs in their understanding of this work.

The workshop was led by Peter Jaszi, a lead principal investigator on CAA’s fair-use project and a professor at American University’s Washington College of Law. After providing a brief history of fair use and how court opinion has evolved on this aspect of copyright law, Jaszi guided participants in analyzing each case study to determine if the use in that instance required copyright permission or if the museum could rely on fair use. Participants referred to CAA’s Code to understand the basic principles and limitations that applied in each case. In every situation, the key question was whether or not the use under consideration was “transformative.” Did it show the work of art in a new context, add to its meaning, or change our understanding of it? Was it an educational use? As the discussion continued, it became apparent that every user of copyrighted materials has to decide for him or herself if a use is fair. One museum might decide that the fair-use doctrine applies to a copyrighted image on the cover of a catalogue, for example, while another museum using the same image on the cover of a similar publication might decide to seek permission. It all depends on how each institution understands its own purpose.

The summit included the following museums: the Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art, Kansas State University; the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art; the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art; the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art; the Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, Johnson County Community College; the Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas; the Ulrich Museum of Art, Wichita State University; and the Wichita Art Museum. As a result of the meeting, the directors and staff of these institutions have decided to continue their work on fair use by sharing documents related to rights and reproductions―donation agreements, artist contracts, and the like. The goal is to develop additional best practices among their museums related to copyright and fair use.

Julian Zugazagoitia, director of the Nelson-Atkins, summarized the accomplishments of the meeting like this: “I think it brought immensely valuable information to all our participants and will allow us to use images in a more robust and self-assured way.” McDonnell also commented: “The CAA Code opens the door to a sea change in art-museum practice related to image use. Arriving at wise conclusions about interpretations of fair use with other art-museum colleagues provided grounded information and confidence about possible new practices.” What better results can one ask for?

Image: Shuttlecock (1994) by Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen on the lawn of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri

CAA’s Fair-Use Specialists Answer Your Questions

posted by Patricia Aufderheide — March 14, 2016

Patricia Aufderheide is a professor in the School of Communication and director of its Center for Media & Social Impact, School of Communication, American University; and Peter Jaszi is a professor at the Washington College of Law, Program on Information Justice and Intellectual Property, American University.

Since CAA’s Code of Best Practices was released in February 2015, we have met with many groups and individuals in the visual arts, and we have witnessed major policy changes taking place across the visual arts field as a result of the Code.

Recently, two major organizations announced an easing of copyright restrictions that will make publishing about art infinitely easier. In late February, the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation announced new guidelines for fair use that will “make images of Rauschenberg’s artwork more accessible to museums, scholars, artists, and the public.” In its press release, the foundation cites the prohibitive costs associated with rights and licensing, as well as the obstacles copyright restrictions create in converting print publications to online formats. http://www.rauschenbergfoundation.org/newsfeed/foundation-announces-pioneering-fair-use-image-policy.

Also in the past few weeks, the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) announced that it is revoking its guidelines on thumbnail images in online publications, which restricted the fair use of works of art to small-scale reproductions with low resolutions. Furthermore, it encouraged its members to rely on CAA’s Code of Best Practices until such time that they prepare new policies of their own. Additional important changes have taken place at Yale University Press, where they now support reliance on fair use in scholarly catalogues, and at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, which relied on CAA’s Code when designing the online catalogue of its collection. Other museums are following suit, as are visual artists.

As we look back on one year living with and promoting the Code, we wanted to pull together some of the most common questions we received, with answers! (You will also find these questions added to the FAQs on CAA’s website.) We have been consistently amazed, but not surprised, by the interest, curiosity, and the sheer will the visual arts field has employed in applying fair use.

—

Is fair use only applicable to non-commercial uses?

Fair use is applicable whether the use is commercial or non-commercial. That fact is very well established in law. Recently, the appeals court decision supporting Google Books’ use of copyrighted books as fair use explicitly says, “Google’s profit motivation does not in these circumstances [that is, Google’s transformative use of the information] justify denial of fair use.” The same would be true when an otherwise qualifying fair use occurred in the setting of a print publication offered for sale.

This is not a new or novel proposition. In fact, for the last 175 years, almost all of the creators who successfully asserted fair use have been engaged in commerce, in a big or small way. That’s because, under the prevailing definition copyright law, most things that we do in our professional lives (write, make art, publish books) are “commercial.” If money will or may change hands, that’s enough – even if the transaction is done without the expectation of profit. So treating commerciality as a knock-out factor would be the death knell of a meaningful fair use doctrine.

It is true that the non-commercial character of a use may be one feature that can add to a fair use claim. But it is not a particularly important one. Likewise, the size of the print run generally is not a relevant consideration in assessing the validity of fair use. The key to fair use is making sure your use is “transformative,” that is, using the material for a different purpose than the market purpose.

There’s more about this at pages 15-16 of the Code.

Is the Code only applicable to the so-called fine arts? What about artists working in design or photography?

The Code is carefully crafted to provide a reasoning framework in five common situations in the visual arts: analytic writing, teaching, making art, museum work, and archive/collections digital display. Any artist, teacher, writer, or curator can apply the Code’s fair use reasoning if they are engaged in one (or several) of these activities. So can students in the field, and so can independent visual arts professionals, and even amateurs. Many of the activities that graphic designers and photographers engage in give rise to the same copyright questions that confront other visual arts professionals. Sometimes, however, their work may involve other issues—trademark questions, for example, contractual disputes, that fall outside the scope of the Code. The important point is that fair use is for everyone, not just for a privileged few.

What if rights holders or brokers such as ARS and VAGA don’t accept my fair use claim?

In the first instance, of course, what is (or isn’t) fair use is for the user to decide. Rights holders and their agents don’t have the last word (or any word) on this determination. And, at least so far, they haven’t chosen to make a case of any situation in which a user proceeded without license. If your uses are made within the terms of the Code, and you are able to explain how that is true, you have such a solid argument for fair use that rights holders will be in deep peril of wasting their money and time by bringing any legal action. That doesn’t mean that “nastygrams”—letters demanding payment or expressing outrage and issuing threats of legal action—couldn’t be sent. People are free to write whatever they want in letters, even if it is not true.

You may decide, of course, not to employ fair use if you think rights holders may see it as an unfriendly act, and decide not to like you any more. Personal relationships matter in any field.

But if a rights holder threatens action in an unrelated area—for instance, threatening to withhold access to an artist for a later project, or to raise fees for an unrelated work to cover the lost license—you might want to document it. This might be an illegal act on their part.

How big can images get under fair use on a website? We used to have the pixel sizes that AAMD prescribed, but they have retired those, and currently refer us to the Code. But the Code has no specifics on that.

The Code offers no specific recommendations on image size for any purpose, and that is a deliberate choice. The heart of fair use is repurposing material and using what is appropriate for that new purpose. Therefore, individual visual arts professionals need to ask themselves what size is appropriate for any image used to accomplish their objectives. The question always is the same: what amount is (or what reproduction quality) is reasonable. And the answer to this question will always vary according to circumstance. The requirements of a scholarly monograph, for example, may be different from those of a local art blog. No one wants a document that provides a reasoning framework across fields to offer numerical prescriptions. That would not only be hazardous legally (uses have to be appropriate to the specific transformative purpose), but would run the risk of being sadly and quickly outdated, given the fast pace of digital change.

The decision of the AAMD to withdraw its 2011 recommendations on the size of “thumbnails” is an illustration of this fact. Only a few years ago, this was a pioneering document, but as visual arts professionals have become more familiar with fair use, and both practices and expectations around the use of images to support discourse (especially on-line) changed, what had once offered freedom came quickly to feel like a straitjacket.

Of course, institutions may still choose to adopt rules of thumb on image size for internal use, to simplify day-to-day decision-making. But these always should yield to case-by-case consideration when they stand in the way of completing worthwhile projects.

I don’t understand how to employ fair use when I have to get an image from a museum or archive. Often, they will want to charge me a fee just to obtain that reproduction.

Yes, if you need someone’s permission to get access to material you need, you can’t rely on fair use to get it. As a practical matter, fair use only can be employed by someone who already has independent access to the same or similar documentation. The flip side of this proposition, of course, is that if you can find appropriate documentation from another source, you don’t have to pay reproduction or access fees to the collection that holds the original. Reproduction and access fees are common; many collections still use them to cover the costs of serving you. Sometimes people confuse these with copyright licenses, but it should be clear in the contract what exactly you’re paying for. Increasingly, public museums are posting images, particularly of works in the public domain, to digital platforms. Their goal is to increase public access and limit the amount of work their own staffs have to do.