CAA News Today

CAA Fair-Use Events in Los Angeles and Saint Louis

posted by CAA — May 19, 2017

A scene from the fair-use workshop at the UCLA Library (photograph by Sharon E. Farb)

On May 5, 2017, CAA hosted “Fair Use and the Visual Arts,” a presentation and panel discussion at the UCLA Library. The event was made possible by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Speakers on the panel included Peter Jaszi, the lead investigator on the CAA Code of Best Practices in Fair Use in the Visual Arts and Professor at American University Washington College of Law in the Program on Information Justice and Intellectual Property, and Janet Landay, Program Manager of the Fair Use Initiative at CAA. The pair, who have given presentations across the U.S. and internationally as part of the CAA Fair Use Initiative, talked about why it was important for CAA to undertake the project, their methodology, and the resulting Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts.

The second half of the event was devoted to a Q&A with the audience of approximately fifty-five people. Question topics ranged from addressing the issue of how the size at which an illustration is produced impacts fair use to indicating in a caption or illustration credits section that I am claiming fair use in the reproduction of an illustration.

A second discussion on CAA’s Fair Use Initiative took place at the American Alliance of Museum’s 2017 Annual Meeting and MuseumExpo in Saint Louis, Missouri. The panel discussion, titled “Copyrighted Material in the Museum: A Path to Fair Use,” took place on May 9. The panel brought together esteemed colleagues from the museum and publishing worlds and was comprised of Patricia Fidler, publisher of art and architecture at Yale University Press; Anne Collins Goodyear, codirector of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art; Judy Metro, editor in chief for the National Gallery of Art; and Joseph Newland, director of publishing for the Menil Collection. Hunter O’Hanian, CAA executive director, was the chair and moderator.

A presenter at AAM’s annual meeting discussed Andrea Wallace’s Still Life Pixel + Metadata Dress (photograph by Anne Young)

About seventy-five to one hundred people attended the standing-room only session and discussion revolved around fair-use issues for museums who want to use their own materials: catalogues, brochures, websites—even wall texts. A key takeaway from the session: museum representatives need to maintain good relations with donor and lenders, and getting approval from their own legal counsel, who tend to approach these matters with caution.

Later in the day Hunter O’Hanian spoke to faculty and students in the Department of Art History and Archaeology at Washington University in Saint Louis.

Learn more about the CAA Fair Use Initiative

Learn more about the 106th CAA Annual Conference in Los Angeles, February 21-24, 2018

CAA Goes to France

posted by CAA — May 08, 2017

The College Art Association has been invited to speak about its Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts at two conferences taking place in France in early June. On June 4 in Fontainebleau, executive director Hunter O’Hanian will participate in a session on “Fair Use and Open Content” at the seventh annual Festival of Art History, along with speakers from the Paul Mellon Center for Studies in British Art (UK), the J. Paul Getty Trust, and the French Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art.

The College Art Association has been invited to speak about its Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts at two conferences taking place in France in early June. On June 4 in Fontainebleau, executive director Hunter O’Hanian will participate in a session on “Fair Use and Open Content” at the seventh annual Festival of Art History, along with speakers from the Paul Mellon Center for Studies in British Art (UK), the J. Paul Getty Trust, and the French Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art.

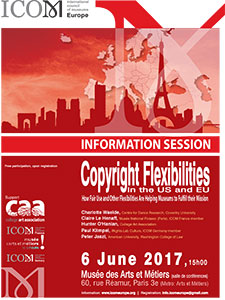

Two days later, on June 6, Hunter will join Peter Jaszi, lead principal investigator on the Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts, in Paris to speak at a session on fair use during the annual conference of ICOM Europe. They will be joined by speakers from England, France, and Germany, to discuss “Copyright Flexibilities in the US and EU: How Fair Use and Other Flexibilities are Helping Museums to Fulfill their Mission.”

Both conferences provide opportunities for CAA to share its work on fair use with EU visual arts professionals. Though this feature of copyright law is virtually unique to the United States, there is increasing interest in Europe to provide greater access to copyrighted materials, especially in the cultural sectors of these countries. Travel costs for CAA’s participation are underwritten by a generous grant from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation.

A CAA Road Trip

posted by Janet Landay, Program Manager, Fair Use Initiative — October 18, 2016

Bowdoin College Museum of Art in Brunswick, Maine (photograph by Janet Landay)

Bowdoin College Museum of Art in Brunswick, Maine (photograph by Janet Landay)In late September, Hunter O’Hanian and I had the pleasure of spending a weekend at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, to attend two CAA events hosted by Anne Goodyear, codirector of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art and a former CAA president. We arrived at the picturesque New England campus on a beautiful fall day. The college’s art museum, one of the oldest in the country, anchors the western edge of the quad, its neoclassical façade presiding gracefully over green lawns and majestic trees where students played Frisbee, read, or walked across campus. It was a perfect weekend to welcome CAA members to campus.

The first group arrived that Saturday afternoon to attend a CAA member reception, the first of several Hunter has planned around the country to provide an opportunity for him to meet with members in a relaxed setting and talk about CAA. The event began with a tour of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art given by Anne and her husband, the museum’s codirector, Frank Goodyear. Immediately following, we all walked a block away to Anne and Frank’s house to enjoy some wine and cheese on their back patio. The fifteen or so participants hailed from several schools and museums in addition to Bowdoin—Colby College, Bates College, the Portland Museum of Art, and the Farnsworth Art Museum—and included art historians, artists, librarians, and independent scholars.

Members spoke in turn about their most memorable CAA experiences: attending a first conference, interviewing and getting a job, meeting old friends, or networking with scholars in their fields. Hunter then shared thoughts about his goals for CAA based on what he has learned from members since he became executive director in July. He observed the importance of connectivity—how to keep CAA members in touch with issues in the field, but especially how to keep them in touch with each other. And he described many of the changes members will experience at the next Annual Conference, including a focus on personal experience, captured by a new theme for the meetings, myCAA.

On Sunday morning, several of the same CAA members returned, joined by others from around the state, for a half-day workshop about copyright and fair use. Peter Jaszi, a co–lead investigator on CAA’s Fair Use Initiative, came from Washington, DC, to Bowdoin to lead the program, which focused on how visual-arts professionals can use CAA’s Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts in their work. Following an introduction to copyright and fair use, the workshop began with a look at how museum professionals can use the Code when employing copyrighted materials in their work.

Participants had been asked to bring real-life questions with them. Thus, a museum director wanted to know whether his museum could allow photography in the galleries of works still protected by copyright. A curator described a challenge she had in getting an image for a catalogue from a museum in central China. When she received no reply from the museum, she resorted to scanning the image from another book. Is that fair use? Other questions involved loan forms, credit lines, and online projects.

As the day continued, the program moved on to address questions from professionals in other areas: librarians and archivists, professors and teachers, artists and independent scholars. Can a faculty member use images in class that she got from a flash drive she had received from a foreign museum? What kind of credit information is necessary for a blog about films? Is Shepard Fairey’s image of Obama a good case study for students learning about fair use? How should the institutional repository on a college campus view the copyright protection of yearbook photographs? By the end of the afternoon, a remarkable range of questions had been discussed, and the forty participants came away with a much greater understanding of fair use and how to rely on it in their work.

Peter Jaszi and Kyle Courtney at CAA’s fair-use town hall at Harvard University (photograph by Janet Landay)

Peter Jaszi and Kyle Courtney at CAA’s fair-use town hall at Harvard University (photograph by Janet Landay)On Monday, Hunter, Peter, and I were in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to join Kyle Courtney, a copyright specialist in Harvard’s Office for Scholarly Communication, for a fair-use town hall on the campus of Harvard University. As in Maine, Peter began the program with an introduction to fair use, and I followed with a description of CAA’s Fair Use Initiative. Kyle spoke about a program he directs at Harvard that trains librarians to be “first responders” to users’ questions about fair use. Although relatively new, the program has proven to be an effective way to support and teach visual-arts professionals about fair use. It is now being replicated on other university campuses. The event was then opened to questions from the sixty-five members of the audience, which Peter and Kyle discussed in depth.

Many of the topics were similar to those that had been addressed at the Bowdoin workshop, but a new subject emerged as well: advocacy. Does a professor who has had a manuscript accepted have any recourse when her publisher requires signed author agreements stating that all images had been cleared for publication and all fees paid? The answer is yes; she can ask her publisher to read CAA’s Code and explain that many, if not all, of her uses of images comply with the doctrine of fair use. While the effort may not succeed (though CAA has several success stories on file), over time it will familiarize publishers with the principles outlined in the Code. Changes have already taken place, in large part due to this kind of challenge from users. Yale University Press now accepts fair-use defenses from its authors who are publishing monographs; the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation embraced a fair use policy for that artist’s work; and CAA not only encourages its authors to consider whether or not their uses are fair, but it also indemnifies authors against lawsuits about works used under fair use.

The program concluded with a reminder that CAA is happy to answer questions about fair use; please don’t hesitate to contact us at nyoffice@collegeart.org.

The CAA member reception at Massachusetts College of Art and Design (photograph by Janet Landay)

The CAA member reception at Massachusetts College of Art and Design (photograph by Janet Landay)Later on Monday, Hunter and I joined another group of CAA members at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design for a wine-and-cheese reception at the school’s President’s Gallery and Bakalar and Paine Galleries. Attendees included a wide range of members, from professors who have belonged to the association for thirty years to new members just graduating from MFA programs. Lisa Tung, the gallery’s director and curator, kicked off the event with a tour of two exhibitions currently on view, Encircling the World: Contemporary Art, Science, and the Sublime and Women’s Rights Are Human Rights: International Posters on Gender-Based Inequality, Violence, and Discrimination. Hunter, who is a former vice president for development at MassArt, then invited participants to speak about how CAA is valuable to them. He emphasized the importance of hearing from members so that CAA can support them as fully as possible in this rapidly changing world.

CAA’s road trip continued in early October with another member’s reception in Portland, Oregon. Later this month we will convene a fair-use workshop in Seattle, Washington. More events are planned for early next year in Georgia and Virginia. Stay tuned!

The Bowdoin College fair-use event was organized by the Bowdoin College Museum of Art and CAA, with funds provided by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The Harvard University fair-use event was organized by Harvard’s Office for Scholarly Communication, thanks to the generous support of the Arcadia Fund, and by CAA, with funds provided by the Mellon Foundation.

Help Us Develop a Fair Use Curriculum!

posted by CAA — May 03, 2016

In 2015, the College Art Association published a Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts that established policies on the fair use of copyrighted materials for professionals in the visual arts field. The Code outlines the principles and limitations for applying the doctrine of fair use in five areas: critical writing, teaching, making art, museum uses, and online access to archives and special collections. It is available online, along with supplementary information, at the Fair Use web page.

With the input of our members, CAA is now developing curriculum materials to help teachers educate their students about fair use so that people entering the field will start out with a basic understanding of this important doctrine. Please help us develop useful materials by completing the following short survey, which is being administered by American University, CAA’s partner on the fair use initiative.

Please complete no later than May 20.

There are only six questions that should take less than five minutes to complete.

Thank you for your help!

Fair Use Is Up to Date in Kansas City

posted by Janet Landay, Program Manager, Fair Use Initiative — April 21, 2016

“Do we have to seek copyright permission to post on our website a scholarly checklist of twentieth-century paintings?” “Our museum wants to put an image of a contemporary sculpture from its collection on an invitation for a fundraiser. Do we need copyright permission?” These are the kinds of questions a group of art-museum professionals discussed at a half-day workshop on copyright and fair use sponsored by CAA with funds provided by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and held at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri, on April 8, 2016.

When Patricia McDonnell, director of the Wichita Art Museum, decided her museum could use input and guidance in applying the policies outlined in CAA’s Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts, she organized a meeting for art museums in her region, believing that the support and information she needed was likely the same as her neighboring colleagues. As a member of CAA’s Task Force on Fair Use, McDonnell was familiar with the approach outlined in the Code, and her primary goal was to design an event that would generate immediate practical results. To that end, the “fair use summit” featured two elements that made it particularly effective. First, each of the eight participating museums was represented by its director, legal counsel, and staff member responsible for rights and reproduction. Second, each museum submitted a case study of a fair-use issue from their institution in advance, thereby providing practical examples for consideration during the workshop. As a result, the pragmatic discussions that took place exemplified the type of analysis necessary to determine on a case-by-case basis if the use of a copyrighted text or image is fair; the talks also unified the participating staffs in their understanding of this work.

The workshop was led by Peter Jaszi, a lead principal investigator on CAA’s fair-use project and a professor at American University’s Washington College of Law. After providing a brief history of fair use and how court opinion has evolved on this aspect of copyright law, Jaszi guided participants in analyzing each case study to determine if the use in that instance required copyright permission or if the museum could rely on fair use. Participants referred to CAA’s Code to understand the basic principles and limitations that applied in each case. In every situation, the key question was whether or not the use under consideration was “transformative.” Did it show the work of art in a new context, add to its meaning, or change our understanding of it? Was it an educational use? As the discussion continued, it became apparent that every user of copyrighted materials has to decide for him or herself if a use is fair. One museum might decide that the fair-use doctrine applies to a copyrighted image on the cover of a catalogue, for example, while another museum using the same image on the cover of a similar publication might decide to seek permission. It all depends on how each institution understands its own purpose.

The summit included the following museums: the Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art, Kansas State University; the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art; the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art; the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art; the Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, Johnson County Community College; the Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas; the Ulrich Museum of Art, Wichita State University; and the Wichita Art Museum. As a result of the meeting, the directors and staff of these institutions have decided to continue their work on fair use by sharing documents related to rights and reproductions―donation agreements, artist contracts, and the like. The goal is to develop additional best practices among their museums related to copyright and fair use.

Julian Zugazagoitia, director of the Nelson-Atkins, summarized the accomplishments of the meeting like this: “I think it brought immensely valuable information to all our participants and will allow us to use images in a more robust and self-assured way.” McDonnell also commented: “The CAA Code opens the door to a sea change in art-museum practice related to image use. Arriving at wise conclusions about interpretations of fair use with other art-museum colleagues provided grounded information and confidence about possible new practices.” What better results can one ask for?

Image: Shuttlecock (1994) by Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen on the lawn of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri

CAA’s Fair-Use Specialists Answer Your Questions

posted by Patricia Aufderheide — March 14, 2016

Patricia Aufderheide is a professor in the School of Communication and director of its Center for Media & Social Impact, School of Communication, American University; and Peter Jaszi is a professor at the Washington College of Law, Program on Information Justice and Intellectual Property, American University.

Since CAA’s Code of Best Practices was released in February 2015, we have met with many groups and individuals in the visual arts, and we have witnessed major policy changes taking place across the visual arts field as a result of the Code.

Recently, two major organizations announced an easing of copyright restrictions that will make publishing about art infinitely easier. In late February, the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation announced new guidelines for fair use that will “make images of Rauschenberg’s artwork more accessible to museums, scholars, artists, and the public.” In its press release, the foundation cites the prohibitive costs associated with rights and licensing, as well as the obstacles copyright restrictions create in converting print publications to online formats. http://www.rauschenbergfoundation.org/newsfeed/foundation-announces-pioneering-fair-use-image-policy.

Also in the past few weeks, the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) announced that it is revoking its guidelines on thumbnail images in online publications, which restricted the fair use of works of art to small-scale reproductions with low resolutions. Furthermore, it encouraged its members to rely on CAA’s Code of Best Practices until such time that they prepare new policies of their own. Additional important changes have taken place at Yale University Press, where they now support reliance on fair use in scholarly catalogues, and at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, which relied on CAA’s Code when designing the online catalogue of its collection. Other museums are following suit, as are visual artists.

As we look back on one year living with and promoting the Code, we wanted to pull together some of the most common questions we received, with answers! (You will also find these questions added to the FAQs on CAA’s website.) We have been consistently amazed, but not surprised, by the interest, curiosity, and the sheer will the visual arts field has employed in applying fair use.

—

Is fair use only applicable to non-commercial uses?

Fair use is applicable whether the use is commercial or non-commercial. That fact is very well established in law. Recently, the appeals court decision supporting Google Books’ use of copyrighted books as fair use explicitly says, “Google’s profit motivation does not in these circumstances [that is, Google’s transformative use of the information] justify denial of fair use.” The same would be true when an otherwise qualifying fair use occurred in the setting of a print publication offered for sale.

This is not a new or novel proposition. In fact, for the last 175 years, almost all of the creators who successfully asserted fair use have been engaged in commerce, in a big or small way. That’s because, under the prevailing definition copyright law, most things that we do in our professional lives (write, make art, publish books) are “commercial.” If money will or may change hands, that’s enough – even if the transaction is done without the expectation of profit. So treating commerciality as a knock-out factor would be the death knell of a meaningful fair use doctrine.

It is true that the non-commercial character of a use may be one feature that can add to a fair use claim. But it is not a particularly important one. Likewise, the size of the print run generally is not a relevant consideration in assessing the validity of fair use. The key to fair use is making sure your use is “transformative,” that is, using the material for a different purpose than the market purpose.

There’s more about this at pages 15-16 of the Code.

Is the Code only applicable to the so-called fine arts? What about artists working in design or photography?

The Code is carefully crafted to provide a reasoning framework in five common situations in the visual arts: analytic writing, teaching, making art, museum work, and archive/collections digital display. Any artist, teacher, writer, or curator can apply the Code’s fair use reasoning if they are engaged in one (or several) of these activities. So can students in the field, and so can independent visual arts professionals, and even amateurs. Many of the activities that graphic designers and photographers engage in give rise to the same copyright questions that confront other visual arts professionals. Sometimes, however, their work may involve other issues—trademark questions, for example, contractual disputes, that fall outside the scope of the Code. The important point is that fair use is for everyone, not just for a privileged few.

What if rights holders or brokers such as ARS and VAGA don’t accept my fair use claim?

In the first instance, of course, what is (or isn’t) fair use is for the user to decide. Rights holders and their agents don’t have the last word (or any word) on this determination. And, at least so far, they haven’t chosen to make a case of any situation in which a user proceeded without license. If your uses are made within the terms of the Code, and you are able to explain how that is true, you have such a solid argument for fair use that rights holders will be in deep peril of wasting their money and time by bringing any legal action. That doesn’t mean that “nastygrams”—letters demanding payment or expressing outrage and issuing threats of legal action—couldn’t be sent. People are free to write whatever they want in letters, even if it is not true.

You may decide, of course, not to employ fair use if you think rights holders may see it as an unfriendly act, and decide not to like you any more. Personal relationships matter in any field.

But if a rights holder threatens action in an unrelated area—for instance, threatening to withhold access to an artist for a later project, or to raise fees for an unrelated work to cover the lost license—you might want to document it. This might be an illegal act on their part.

How big can images get under fair use on a website? We used to have the pixel sizes that AAMD prescribed, but they have retired those, and currently refer us to the Code. But the Code has no specifics on that.

The Code offers no specific recommendations on image size for any purpose, and that is a deliberate choice. The heart of fair use is repurposing material and using what is appropriate for that new purpose. Therefore, individual visual arts professionals need to ask themselves what size is appropriate for any image used to accomplish their objectives. The question always is the same: what amount is (or what reproduction quality) is reasonable. And the answer to this question will always vary according to circumstance. The requirements of a scholarly monograph, for example, may be different from those of a local art blog. No one wants a document that provides a reasoning framework across fields to offer numerical prescriptions. That would not only be hazardous legally (uses have to be appropriate to the specific transformative purpose), but would run the risk of being sadly and quickly outdated, given the fast pace of digital change.

The decision of the AAMD to withdraw its 2011 recommendations on the size of “thumbnails” is an illustration of this fact. Only a few years ago, this was a pioneering document, but as visual arts professionals have become more familiar with fair use, and both practices and expectations around the use of images to support discourse (especially on-line) changed, what had once offered freedom came quickly to feel like a straitjacket.

Of course, institutions may still choose to adopt rules of thumb on image size for internal use, to simplify day-to-day decision-making. But these always should yield to case-by-case consideration when they stand in the way of completing worthwhile projects.

I don’t understand how to employ fair use when I have to get an image from a museum or archive. Often, they will want to charge me a fee just to obtain that reproduction.

Yes, if you need someone’s permission to get access to material you need, you can’t rely on fair use to get it. As a practical matter, fair use only can be employed by someone who already has independent access to the same or similar documentation. The flip side of this proposition, of course, is that if you can find appropriate documentation from another source, you don’t have to pay reproduction or access fees to the collection that holds the original. Reproduction and access fees are common; many collections still use them to cover the costs of serving you. Sometimes people confuse these with copyright licenses, but it should be clear in the contract what exactly you’re paying for. Increasingly, public museums are posting images, particularly of works in the public domain, to digital platforms. Their goal is to increase public access and limit the amount of work their own staffs have to do.

CAA Celebrates National Fair Use Week

posted by Janet Landay, Program Manager, Fair Use Initiative — February 22, 2016

The College Art Association is proud to participate in the 2016 National Fair Use Week. This event is held annually during the last week of February, this year from Monday, February 22, through Friday, February 26. It celebrates the important doctrines of fair use in the United States and fair dealing in Canada and other jurisdictions. In honor of National Fair Use Week, CAA presents the following article about ways its fair use code has been embraced in the year since it was first released.

It’s been exactly one year since CAA published its Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts. A session at this year’s Annual Conference took stock of the progress made during the past twelve months, and panelists recounted remarkable progress in applying fair use to the visual arts. Chaired by Judy Metro, editor-in-chief at the National Gallery of Art and chair of CAA’s Committee on Intellectual Property, five CAA members described how they or their institutions modified their approach to using copyrighted materials because of CAA’s new Code.

Leading the way was the College Art Association itself, which overturned its copyright policies for authors. As Betty Leigh Hutcheson, CAA’s director of publications, explained, instead of demanding that authors get permissions for all images and indemnify the press, CAA’s contracts now ask authors to read the Code and apply it to their uses. Indemnification is no longer required when asserting fair use.

Other publishers of artwork also told of changing policy. Patricia Fidler, art publisher at Yale University Press, described how, inspired by the Code, the press has now created its own fair use guidelines specific to scholarly publishing. Just as important for Fidler is the fact that other parts of Yale University, including its museums, are now considering expanding their access to fair use. “It’s a big step,” she said, “to give authors the last word on their fair use. And we are proud that it says at the top of our new author guidelines, ‘Yale University Press supports the fair use of art images in scholarly monographs.’”

Other publishers of artwork also told of changing policy. Patricia Fidler, art publisher at Yale University Press, described how, inspired by the Code, the press has now created its own fair use guidelines specific to scholarly publishing. Just as important for Fidler is the fact that other parts of Yale University, including its museums, are now considering expanding their access to fair use. “It’s a big step,” she said, “to give authors the last word on their fair use. And we are proud that it says at the top of our new author guidelines, ‘Yale University Press supports the fair use of art images in scholarly monographs.’”

Joseph Newland, head of publications at the Menil Collection in Houston, announced new policies at his museum. Thanks to the Code, the Menil has expanded access to fair use throughout the institution by adapting CAA’s policy for internal criteria. He said improvements are already apparent: “It’s really helped work flow, especially at the press office, which often needs to respond to the news cycle in a timely way.”

Sometimes progress includes learning from frustration. Susan Higman Larsen, head of publications at the Detroit Institute of Arts, talked about having to publish a work in a scholarly catalogue without a relevant image, because of intolerable attempts at controlling content by an estate. “We misunderstood fair use,” she explained. “We didn’t understand that some commercial uses are just as eligible for fair use as non-commercial ones.” The Code helped clear that up, she said, and now the DIA is publishing a new book, in which the author wants to reproduce an image by the same artist. “This time, we’ll claim fair use,” she said. Furthermore, the DIA is considering changing its institutional policies about fair use.

Sometimes progress includes learning from frustration. Susan Higman Larsen, head of publications at the Detroit Institute of Arts, talked about having to publish a work in a scholarly catalogue without a relevant image, because of intolerable attempts at controlling content by an estate. “We misunderstood fair use,” she explained. “We didn’t understand that some commercial uses are just as eligible for fair use as non-commercial ones.” The Code helped clear that up, she said, and now the DIA is publishing a new book, in which the author wants to reproduce an image by the same artist. “This time, we’ll claim fair use,” she said. Furthermore, the DIA is considering changing its institutional policies about fair use.

The last success story of the session was from an artist, Rebekah Modrak, who teaches at the University of Michigan. She recounted the challenges she encountered after creating a work of art that incorporated copyrighted material. She made a video introducing an imaginary company, Re Made Co., that spoofed the overexemplifying hipster-Brooklyn site Best Made Co. After receiving a cease-and-desist letter, she turned for advice to CAA, which steered her to good legal advice at the University of Michigan. Her university’s lawyers welcomed the opportunity to support her fair uses and endorsed her intention to keep her video online. Modrak then published an account of her experience for a Routledge publication, Consumption Markets & Culture. When the editors there initially asked her to get permission to reproduce images from her video, she relied on CAA’s Code to persuade them that fair use would apply.

The last success story of the session was from an artist, Rebekah Modrak, who teaches at the University of Michigan. She recounted the challenges she encountered after creating a work of art that incorporated copyrighted material. She made a video introducing an imaginary company, Re Made Co., that spoofed the overexemplifying hipster-Brooklyn site Best Made Co. After receiving a cease-and-desist letter, she turned for advice to CAA, which steered her to good legal advice at the University of Michigan. Her university’s lawyers welcomed the opportunity to support her fair uses and endorsed her intention to keep her video online. Modrak then published an account of her experience for a Routledge publication, Consumption Markets & Culture. When the editors there initially asked her to get permission to reproduce images from her video, she relied on CAA’s Code to persuade them that fair use would apply.

Another way CAA is measuring the impact of the Code is through annual surveys that provide longitudinal data on how CAA members are relying on fair use. At the conference session, Patricia Aufderheide shared early results from a recent 2,500-person CAA survey, showing broad awareness of the Code. More than two thirds of respondents indicated they knew about the Code, and a third of that group had already shared their knowledge, usually with more than one kind of interlocutor—for example, students, colleagues, and association members. Many of those aware of the Code had already put it to use. Indeed, 11% of all respondents had begun to employ fair use only after the appearance of the Code last year, a big leap and a demonstration of the power of understanding community values and best practice.

Peter Jaszi concluded the session by discussing next steps in CAA’s fair use efforts. Over the coming year he and Aufderheide will work to educate in-house legal counsel about the importance of mission-oriented fair use, resulting in expanded employment of fair use by museums. They will continue to give presentations about the Code to groups of arts professionals around the country, with a special focus on publishing and museum activities. And Jaszi encouraged CAA members to avail themselves of the many resources—FAQs, explainers, infographics, background documents, slideshows and more—available both on the CAA website and at the Center for Media & Social Impact.

CAA will be posting updates about fair use on its website, including the success stories described above. We would like to hear from any of you whose practices have changed because of the Code, whether you have a success story or a challenge to share. Both types of information will support the field’s efforts to make appropriate reliance on fair use the norm. If you have fair use news to share, please contact me at jlanday@collegeart.org.

CAA will be posting updates about fair use on its website, including the success stories described above. We would like to hear from any of you whose practices have changed because of the Code, whether you have a success story or a challenge to share. Both types of information will support the field’s efforts to make appropriate reliance on fair use the norm. If you have fair use news to share, please contact me at jlanday@collegeart.org.

Find out more about National Fair Use Week here: http://fairuseweek.org/

Below are links to some of the events taking place around the country:

https://blog.library.gsu.edu/2015/02/23/fair-use-week/

http://www.udel.edu/udaily/2016/feb/fair-use-week-021716.html

A comprehensive collection of fair use codes, articles, videos and teaching materials can be found at the Center for Media and Social Impact, http://www.cmsimpact.org/fair-use

And don’t forget to look at the materials available on CAA’s website, which focus on our fair use code. There you will find Frequently Asked Questions, explanatory videos, infographics, and a five-part webinar, along with the Code itself.

Image Captions

Betty Leigh Hutcheson (photograph by Bradley Marks)

Patricia Fidler (photograph by Bradley Marks)

Joseph Newland, Peter Jaszi, and Susan Higman Larsen (photograph by Bradley Marks)

Rebekah Modrak (photograph by Bradley Marks)

Rebekah Modrak, Fair Use Badge of Honor

CAA Presents Its Fair-Use Code to Leaders of Artist-Endowed Foundations

posted by Janet Landay, Program Manager, Fair Use Initiative — November 16, 2015

On October 30, CAA gave a presentation about its Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts to participants at an all-day Leadership Forum organized by the Aspen Institute’s Artist-Endowed Foundations Initiative (AEFI). Attending the event were directors and board members of approximately seventy foundations, such as the Warhol Foundation, the Rauschenberg Foundation, the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, and many others. Speaking on behalf of CAA were Richard Dannay, an intellectual property attorney at Cowan Liebowitz & Latman, and a member of the legal advisory committee for the fair use project; Christine Sundt, editor of the journal Visual Resources and a fair use task force member and project advisor; and Anne Collins Goodyear, co-director of the Bowdoin College Art Museum, a principal investigator for the fair use project, and past-president of CAA, under whose leadership the initiative began.

On October 30, CAA gave a presentation about its Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts to participants at an all-day Leadership Forum organized by the Aspen Institute’s Artist-Endowed Foundations Initiative (AEFI). Attending the event were directors and board members of approximately seventy foundations, such as the Warhol Foundation, the Rauschenberg Foundation, the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, and many others. Speaking on behalf of CAA were Richard Dannay, an intellectual property attorney at Cowan Liebowitz & Latman, and a member of the legal advisory committee for the fair use project; Christine Sundt, editor of the journal Visual Resources and a fair use task force member and project advisor; and Anne Collins Goodyear, co-director of the Bowdoin College Art Museum, a principal investigator for the fair use project, and past-president of CAA, under whose leadership the initiative began.

Invited by Christine Vincent, project director of the Aspen Institute’s program, this was a unique opportunity for CAA to share the new Code. As caretakers of their artist’s lifetime works, these foundation directors are greatly concerned with the quality and accuracy of images and factual information published about them, as well as the protection of the artists’ reputations. This panel presented the thinking behind the principles and limitations to the doctrine of fair use that can ally the goals and interests of both copyright holders and users of copyrighted works.

Moderated by Stephen K. Urice, professor of law at the University of Miami School of Law and advisor to the Aspen Institute’s program, Richard Dannay began the panel with a definition of fair as stated in U.S. copyright law. He outlined the doctrine’s importance in providing room for creators to use copyrighted materials under certain circumstances without seeking copyright permission. These “fair uses” of copyright are in contrast to “infringing uses” and exist when the copyrighted materials are being used for qualifying interpretive or creative purposes. He then outlined the four factors listed in the Copyright Act of 1976 that help determine whether a purpose falls under fair use and went on to discuss the notion of transformative use: whether it “adds something new, with a further purpose or difference character.” In conclusion, Dannay emphasized the importance of understanding these considerations when determined whether or not a use of copyrighted materials can be considered fair or not; each instance of fair use is determined separately, based on the specifics of each case.

Christine Sundt spoke next about CAA’s longstanding commitment to copyright issues. “…the question of how to apply US law to our practices as artists and art historians, especially the doctrine of fair use, has been a recurring theme at our annual conferences for decades. Our members wanted answers and direction because they faced uncertainty and even disappointment in either trying to seek the law’s benefits as creators or when attempting to use rights lawfully as interpreters of art. Copyright is meant to be a balanced right but it was often impossible to see where or how this balance works.”

Sundt described CAA’s collaboration with the National Initiative for a Networked Cultural Heritage and the American Council of Learned Societies between 1997 and 2003 to sponsor workshops and discussion forums at conferences and universities, and, in collaboration with sister organizations, to explore the benefits, effects, and consequences of fair use to CAA’s wide and varied constituencies. She added that the association has also developed policies regarding orphan works. “When creative works are abandoned or not properly identified with a creator’s name, what should be required in order to use these works in transformative ways that revived them from obscurity? CAA’s members wanted direction about being innovative and creative while remaining ethical and lawful. CAA participated in the hearings on Orphan Works and prepared several amicus briefs when asked to provide opinions.”

The last speaker was Anne Goodyear, who described the best practices outlined in the Code, the method by which they were derived, and how CAA has implemented the Code since it was published in February. She cited the extensive research conducted by the authors of CAA’s Code of Best Practices, Peter Jaszi and Pat Aufderheide, including confidential interviews with 100 leaders in the field (a small number of whom represented artist’s estates.) The study revealed that many of the concerns CAA members had about copyright restrictions grew largely out of uncertainty about how and when fair use might apply to the development of new interpretive projects. “A principle aim for CAA,” she stated, “has thus been to educate visual arts professionals about its application.”

Next, Jaszi and Aufderheide met in small groups with a wide range of visual arts practitioners in five cities across the United States. Based on the information gleaned from these meetings a series of five fair use principles, each with attendant limitations, were developed in the following areas: analytic writing, teaching about art, making art, museum uses, and online access to archival and special collections.

Goodyear proceeded, “The third phase of the project brings us here today: the dissemination of the Code. On that note, it is worth stressing that CAA’s Code of Best Practices does not dictate specific standards, but instead provides flexible strategies to evaluate if a given use, whether traditional or innovative, is likely to be considered fair, even as applicable professional standards evolve. The Code will thus provide an enduring tool for both those who use and those who protect copyrighted materials as we work together to foster new creative insight and new knowledge.” She went on to describe ways in which the field is beginning to change, starting at CAA itself, where new author agreements invite contributors to its journals to rely on fair use if, based on a careful reading of the Code, they believe their use of the copyrighted materials falls within the principles and limitations described there. In conclusion, she pointed to the many endorsements the Code has received from professional associations, as well anecdotal evidence that in only eight months since its publication, the document is providing a greater sense of confidence to individuals and organizations wishing to use copyrighted materials in their scholarly and creative work.

The panel concluded with numerous questions from the floor, indicating the great interest in the topic by the artist-endowed foundation directors attending the event. Now that this community knows more about CAA’s fair use code, we hope more conversations will ensue to make reliance on it increasingly useful to the field. More information about the Aspen Institute’s Artist-Endowed Foundations Initiative can be found at www.aspeninstitute.org/aefi.

Image: Participants in CAA’s panel on fair use. From left to right: Richard Dannay, Christine Sundt, Anne Goodyear, Stephen Urice.

Presentation of CAA’s Fair-Use Code in New York

posted by Janet Landay, Program Manager, Fair Use Initiative — October 01, 2015

“CAA’s Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts: How Will It Help the Visual Arts Community?” is the name of a free presentation by Peter Jaszi, lead principal investigator of CAA’s fair-use project, that will take place at the New York Foundation for the Arts (NYFA) in Brooklyn on Tuesday, October 20, 2015, 6:00–7:30 PM. Jaszi will explain how the Code works, how it was created, and why it’s reliable. The presentation will be followed by a Q&A.

When can an artist or art historian use a photo she snapped in a museum for teaching? Can a museum reproduce an image from an exhibition of contemporary art in a related brochure without licensing it? How can fair use simplify the permissions process in publications? Can an archive put images from its collection online—and if so, with what restrictions? The copyright doctrine of fair use, which permits use of unlicensed copyrighted material, has great utility in the visual arts. But for too long, it’s been hard to understand how to interpret this rather abstract part of the law. The newly created Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts, produced by CAA, makes it much easier to employ fair use to do scholarship in the visual arts, art practice, teaching, exhibitions, digital displays, and more.

The event will be held at NYFA’s office at 20 Jay Street, Suite 740, Brooklyn, NY 11201 (F train to York Street Station or A train to High Street/Brooklyn Bridge Station). The talk is free and open to the public but requires an RSVP via Eventbrite. The event is made possible by CAA, with a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

About the Presenter

Peter Jaszi is a professor of law at American University’s Washington College of Law, where he teaches copyright law and courses in law and cinema. He also supervises students in the Glushko-Samuelson Intellectual Property Law Clinic, which he helped to established, along with the Program on Intellectual Property and Information Justice. Jaszi has served as a trustee of the Copyright Society of the USA and is a member of the editorial board of its journal. A graduate of Harvard Law School (JD) and Harvard University (AB), he has written about copyright history and theory and coauthored Reclaiming Fair Use: How to Put Balance Back in Copyright (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011) with Patricia Aufderheide.

CAA’s Fair Use Code Receives a Key Endorsement

posted by Christopher Howard — September 04, 2015

On September 3, the Visual Resources Association announced its endorsement of CAA’s Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts, bringing to seven the number of leading associations to support this work. (https://www.collegeart.org/news/2015/07/13/caas-fair-use-code-receives-important-new-endorsements/) In its expression of support, VRA stated: “The Visual Resources Association (VRA) heartily endorses the College Art Association’s Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts. This code attempts to find consensus across varied constituencies working in the field of visual arts, offering useful models for bridging the divide between those who produce works of art, those who study works of art in academic settings, and those who preserve and provide access to the work produced by the first two groups…. To visual resource and allied image professionals, a key strength of the CAA Code lies in its codification of the historically scrupulous nature of our community of practitioners. In its recommendation that practitioners continue to follow accepted professional standards for metadata, privacy and confidentiality, and the consistent use of terms and conditions, the CAA Code provides a resolute assertion on behalf of our community of practice that courts may refer to when considering fair use parameters.”

Founded in 1982, the Visual Resources Association is a multi-disciplinary organization dedicated to furthering research and education in the field of image and media management within the educational, cultural heritage, and commercial environments. The Association is committed to providing leadership in the visual resources field, developing and advocating standards, and offering educational tools and opportunities for the benefit of the community at large. VRA implements these goals through publication programs and educational activities. For more information about the association, see http://vraweb.org/.

CAA welcomes other endorsements, and encourages organizations in the field to recommend the Code to members. CAA representatives are happy to address questions and to make educational presentations. To make arrangements for a presentation, whether by webinar, conference call, or in person, please contact me at jlanday@collegeart.org. The Code and supporting materials are available at www.collegeart.org/fair-use.

The creation of CAA’s Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts was funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, with additional support provided by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation.