CAA News Today

Getty Supports the CAA-Getty International Program for a Seventh Year

posted by CAA — June 05, 2017

The Getty Foundation has awarded the College Art Association (CAA) a grant to fund the CAA-Getty International Program for a seventh consecutive year. The Foundation’s support will enable CAA to bring twenty international visual-arts professionals to the 106th Annual Conference, taking place February 21-24, 2018 in Los Angeles, CA. Fifteen individuals will be first-time participants in the program and five will be alumni, returning to present papers during the conference. The CAA-Getty International Program provides funds for travel expenses, hotel accommodations, per diems, conference registrations, and one-year CAA memberships to art historians, artists who teach art history, and museum curators. The program will include a one-day preconference colloquium on international issues in art history on February 20, this year to be held at the Getty Center.

The Getty Foundation has awarded the College Art Association (CAA) a grant to fund the CAA-Getty International Program for a seventh consecutive year. The Foundation’s support will enable CAA to bring twenty international visual-arts professionals to the 106th Annual Conference, taking place February 21-24, 2018 in Los Angeles, CA. Fifteen individuals will be first-time participants in the program and five will be alumni, returning to present papers during the conference. The CAA-Getty International Program provides funds for travel expenses, hotel accommodations, per diems, conference registrations, and one-year CAA memberships to art historians, artists who teach art history, and museum curators. The program will include a one-day preconference colloquium on international issues in art history on February 20, this year to be held at the Getty Center.

The deadline for applications is August 21, 2017. Guidelines and application.

The CAA-Getty International Program was established to increase international participation in CAA and the CAA Annual Conference. The program fosters collaborations between North American art historians, artists, and curators and their international colleagues and introduces visual arts professionals to the unique environments and contexts of practices in different countries.

Since the CAA-Getty International Program’s inception in 2012, ninety scholars have participated in CAA’s Annual Conference. Historically, the majority of international registrants at the conference have come from North America, the United Kingdom, and Western European countries. The CAA-Getty International Program has greatly diversified attendance, adding scholars from Central and Eastern Europe, Russia, Africa, Asia, Southeast Asia, Caribbean countries, and South America. The majority of the participants teach art history (or visual studies, art theory, or architectural history) at the university level; others are museum curators or researchers.

Earlier this year, CAA organized a reunion to celebrate five successful years of the CAA-Getty International Program. Twenty alumni were selected to present papers at the Annual Conference in New York, held February 15-18, 2017. Organized into four sessions about international topics in art history, these Global Conversations were chaired by distinguished scholars from the United States and featured presentations by the CAA-Getty alumni.

Read Global Conversations: 20 Papers from the 2017 CAA-Getty Alumni

One measure of the program’s success is the remarkable number of international collaborations that have ensued, including an ongoing study of similarities and differences in the history of art among Eastern European countries and South Africa, attendance at other international conferences, publications in international journals, and participation in panels and sessions at subsequent CAA Annual Conferences. Former grant recipients have become ambassadors of CAA in their countries, sharing knowledge gained at the Annual Conference with their colleagues at home. The value of attending a CAA Annual Conference as a participant in the CAA-Getty International Program was succinctly summarized by alumnus Nazar Kozak, Senior Researcher, Department of Art Studies, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine “To put it simply, I understood that I can become part of a global scholarly community. I felt like I belong here.”

About CAA

The College Art Association is the world’s largest professional association for artists, art historians, designers, arts professionals, and arts organizations. CAA serves as an advocate and a resource for individuals and institutions nationally and internationally by offering forums to discuss the latest developments in the visual arts and art history through its Annual Conference, publications, exhibitions, website, and other programs, services, and events. CAA focuses on a wide range of advocacy issues, including education in the arts, freedom of expression, intellectual-property rights, cultural heritage and preservation, workforce topics in universities and museums, and access to networked information technologies. Representing its members’ professional needs since 1911, CAA is committed to the highest professional and ethical standards of scholarship, creativity, criticism, and teaching.

About the Getty Foundation

The Getty Foundation fulfills the philanthropic mission of the Getty Trust by supporting individuals and institutions committed to advancing the greater understanding and preservation of the visual arts in Los Angeles and throughout the world. Through strategic grant initiatives, it strengthens art history as a global discipline, promotes the interdisciplinary practice of conservation, increases access to museum and archival collections, and develops current and future leaders in the visual arts. It carries out its work in collaboration with the other Getty Programs to ensure that they individually and collectively achieve maximum effect.

Southeast of Now: Introducing a New Journal about Contemporary and Modern Asian Art

posted by Chye Shu Wen, Publicity and Marketing Manager at National University of Singapore Press — May 25, 2017

One of the great challenges of our time is to make sense of the world on a global scale, even while facing ever more urgent concerns at various local levels. While artists, curators, critics, and scholars of art have embraced this challenge for some time now, the global discourse of contemporary and modern art remains stubbornly asymmetrical, with many contexts for discussion oriented to the North and the West, and also to the new and the now.

Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia was established by a collective of scholars and curators as a discursive space for creating encounters between critical texts of contemporary and modern art produced in, from, and around Southeast Asia. The editorial board includes researchers from Singapore, Thailand, Indonesia, Philippines, Australia, New Zealand, Cambodia, and Malaysia. It is presently the only scholarly journal dedicated to the recent art of this region.

The journal presents a necessarily diverse range of views not only on the contemporary and modern art of Southeast Asia, but indeed of the region itself: its borders, its identity, its efficacy, and its limitations as a geographical marker and a conceptual category. As such, the journal is defined by a commitment to the need for and importance of rigorous discussion of the contemporary and modern art of the domain that lies south of China, east of India, and north of Australia.

The journal presents a necessarily diverse range of views not only on the contemporary and modern art of Southeast Asia, but indeed of the region itself: its borders, its identity, its efficacy, and its limitations as a geographical marker and a conceptual category. As such, the journal is defined by a commitment to the need for and importance of rigorous discussion of the contemporary and modern art of the domain that lies south of China, east of India, and north of Australia.

Why ‘Southeast’ of ‘Now’?

The title of the journal has a playful yet provocative function as a reminder that Southeast Asia is named, and to a large extent discursively defined, in relation to an imagined geographical center in the North and the West. It is also a reminder that discussions of contemporary and modern art are increasingly framed by an imagined temporal center: that of the now.

The lack of educational infrastructure of art history in most countries in Southeast Asia was one of the principal motivations behind the creation of the journal. Resisting the pressure to be always up-to-date and forever new, the journal instead values the historicizing of recent practices, from the nineteenth century (and before) to the present (and after). This historical perspective is a foundation for contributions which may otherwise draw on a diverse range of disciplines and methodologies.

Of Themes and Form(ations)

The playful disquiet evoked by the title of the journal, which troubles linear notions of space-time and destabilizes any certainty of an imagined temporal center, gave rise to the inaugural volume’s theme: Discomfort. The provocations that the Southeast of Now editorial collective sought included pieces that reflect on the burdens and future possibility of wielding “regionalism” as a framework. The editors hope to locate this source of tension and anxiety through various discourses and narratives. Texts published in the journal’s first issue suggest also the possibility to discover some comfort within unease, even if merely within shared discomfort.

One key feature of the journal is the inclusion of less academically-driven sections (‘Interview’, ‘Archive’, ‘Artists’ Projects’ and ‘Review’)—spaces the editors felt were necessary for creating discourses about contemporary and modern Southeast Asian art, and providing access to conversations that are already ongoing. It was important for them to create an open platform within the journal where they could create opportunities for artistic responses as well as scholarly articles. Many contemporary artists are engaged in artistic research and are eager to present their views in formats other than written texts, essays, or reviews.

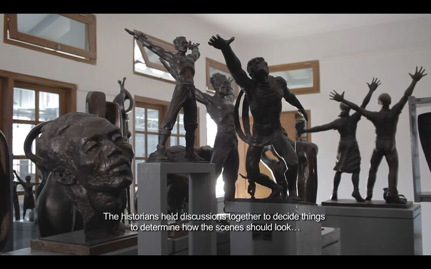

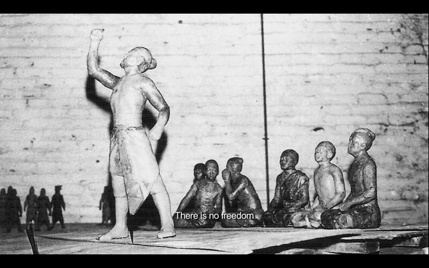

Images from video interview with Pak Edhi Sunarso by Tom Nicholson and Grace Samboh

In Volume 1, Number 1, for example, the section titled Artists’ Projects features a video by Tom Nicholson and Grace Samboh, in which they documented their interview with Pak Edhi Sunarso, one of Indonesia’s most eminent sculptors. Southeast of Now is a fitting place where this kind of research material could travel beyond the site of the physical exhibition in which it was originally viewed, which was the Jakarta Biennale. Within the context of the journal it is not only an artwork to be experienced; it is also a primary source of research material about a valuable figure in Indonesia’s modern art history.

The structure of the journal also provides numerous curatorial possibilities. The Artists’ Projects pages offer a space for a specifically curated sequence of images or texts, either by a member of the editorial collective, a guest curator, or a respondent to a call for proposals. This follows new approaches to publishing where printed matter may be considered as an exhibition format in two-dimensional form. In future issues the editors will alternate such presentations with archival pages from various collections within and beyond the region, as well as translations and other resources.

The Art of Re/De-Categorizing

Southeast of Now effectively aims to be a platform where the categories of “contemporary and modern art,” indeed of “art” in general, as much as the category of “Southeast Asia” itself, will always be open for debate. The editors anticipate continuous challenges in redefining these categories, by looking at aspects of culture that do not usually qualify as “art,” by treating the region’s borders as fluid, and also by looking at research that transcends these borders.

The journal strives to remain committed to the importance of an historical approach, however interwoven with methodologies from other disciplines and practices. The editors hope that future issues of the journal will look further back in time, to the nineteenth century (and before) with the goal of placing the historical research in dialogue with issues of today.

****

The journal is published by the National University of Singapore Press and it is published twice a year (March and October), in print and online via Project MUSE.

To find out more about submission guidelines and subscription information, visit www.southeastofnow.com or the National University of Singapore Press website.

Images from video interview with Pak Edhi Sunarso by Tom Nicholson and Grace Samboh

CAA Amicus Brief on Trump’s Travel Ban

posted by CAA — May 22, 2017

CAA added its name to two amicus briefs in opposition to the United States president’s travel ban, officially known as Executive Order 13,780. We joined the Association of Art Museum Directors and American Alliance of Museums, along with ninety-four art museums. The cases are: International Refugee Assistant Project v. Donald J. Trump in the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit; and State of Hawaii and Ismail Elshikh v. Donald J. Trump in the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.

CAA added its name to two amicus briefs in opposition to the United States president’s travel ban, officially known as Executive Order 13,780. We joined the Association of Art Museum Directors and American Alliance of Museums, along with ninety-four art museums. The cases are: International Refugee Assistant Project v. Donald J. Trump in the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit; and State of Hawaii and Ismail Elshikh v. Donald J. Trump in the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.

The brief argues that the travel ban inhibits the work of museums. “The negative effects of the Order are already being felt,” the document reads, “as several museums have postponed or canceled future exhibitions that require foreign artists, lenders, collectors, curators, scholars, couriers, and others whose ability to contribute can no longer be assured.” Specific examples include the Cleveland Museum of Art, which canceled a music performance, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, which has doubts about securing loans for an exhibition of Persian art.

We consider joining this amicus brief as inherent to our advocacy efforts and our international reach at CAA. The travel ban impacts the international attendees of our Annual Conference, it impinges on the flow of information and discussion between colleagues, and it harms the practice of research more broadly.

GLOBAL CONVERSATIONS 2017

posted by CAA — May 18, 2017

2017 CAA-Getty International Program Reunion Participants

Front row, left to right: Ana Mannarino (Brazil); Ding Ning (China); Sarena Abdullah (Malaysia); Rosa Gabriella Gonçalves (Brazil); Abiodun Akande (Nigeria); Sandra Uskokovic (Croatia); Hugues Heuman Tchana (Cameroon); Parul Mukerji (India); Ceren Ozpinar (Turkey); Irena Kossowska (Poland)

Second row, left to right: Nazar Kozak (Ukraine); Georgina Gluzman (Argentina); Shao Yiyang (China); Ljerka Dulibic (Croatia); Khademul Haque (Bangladesh); Janet Landay (CAA Program Director, USA); Richard Gregor (Slovakia); Davor Dzalto (Serbia); Portia Malatje (South Africa); Cristian Nae (Romania); Laris Boric (Croatia)

The following papers on international topics in art history were presented at four sessions during the 2017 Annual Conference. Organized to commemorate five years of the CAA-Getty International Program, each session includes five alumni scholars from around the world, joined by a distinguished scholar from the United States. The papers can be read in their entirety at the links below.

GLOBAL CONVERSATIONS I

Unsettling the Discipline: Decolonizing the Curriculum

Chair: Michael Ann Holly, Clark Art Institute

Decolonizing the Curriculum: Synthesizing “Multiple Consciousness” into the Art History Curricula of Nigeria and Ghana

Abiodun Akande, Emmanuel Alayande College of Education Oyo, Nigeria

The Emancipatory Potential of Karaman’s Concept of “Peripheral Art”: Still Operative?

Laris Borić, University of Zadar, Croatia

“Does this really matter?” Art History, Feminism, and Peripheral Positions

Georgina Gluzman, Universidad de San Andrés, Argentina

Decolonizing in the Age of Globalization: Experience of a Bangladeshi Art Historian

AKM Khademul Haque, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh

Dangers of Eurocentrism and the Need to Indigenize African and Grassfields Histories

Hugues Heumen Tchana, Higher Institute of the Sahel, University of Maroua, Cameroon

GLOBAL CONVERSATIONS II

Dominant Ideologies and Political Trauma: Can Art History Be Reborn?

Chair: Frederick M. Asher, University of Minnesota

After the Wall: Cultural Trauma and Methodological Challenges in Polish Art History

Irena Kossowska, Institute of Art, Polish Academy of Sciences/Nicolaus Copernicus University, Poland

How My Art History Was Reborn

Nazar Kozak, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine

d.o.a.

Portia Malatjie, Goldsmiths, University of London (South Africa)

Visible and Invisible: How Art History Can Be Reborn from Dominant Ideology in China

Shao Yiyang, Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing, China

“Reconstructing” Art History

Sandra Uskoković, University of Dubrovnik, Croatia

GLOBAL CONVERSATIONS III

The Trouble with (The Term) Art

Chair: Mary Miller, Yale University

SENI MODEN as an Evolving Term and Practice in Malaysian Art

Sarena Abdullah, School of the Arts, Universiti Sains Malaysia

“When Did Beauty Become So F…n’ Ugly?” Troubles with Art and Its Functions

Davor Džalto, The Institute for the Study of Culture and Christianity, Belgrade/American Academy in Rome (Serbia)

Short Introduction on Applying the “Homonymic Curtain” to Recent Exhibitions

Richard Gregor, Trnava University, Slovakia

Art History and Cultural Hegemony in Brazil: the Risks of Misunderstanding Indigenous Art and Colonial Art

Ana Mannarino, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Why Is the Miniature Painting Not History?

Ceren Özpınar, University of Sussex (Turkey)

GLOBAL CONVERSATIONS IV

Transnational Collaborations and Interdisciplinarity: Generating New Knowledge

Chair: David J. Roxburgh, Harvard University

Tracing the Transfer of Cultural Objects/Challenging the Burdens of the Past

Ljerka Dulibic, Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Croatia

Aby Warburg and the Science Without a Name

Rosa Gabriella de Castro Gonçalves, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Brazil

Decolonizing Mimesis: Mad Metaphors and Slippery Similarities in a Classical Sanskrit Text on Painting

Parul Dave Mukherji, Jawaharlal Nehru University, India

Decolonizing Cartography? Visual Culture and the Poetics of Space in Critical Contemporary Art

Cristian-Emil Nae, George Enescu National University of Arts, Romania

Chinese Blue-and-White Porcelain in Western Painting

Ding Ning, Peking University, China

CAA Goes to France

posted by CAA — May 08, 2017

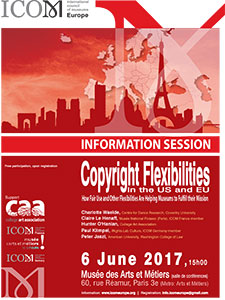

The College Art Association has been invited to speak about its Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts at two conferences taking place in France in early June. On June 4 in Fontainebleau, executive director Hunter O’Hanian will participate in a session on “Fair Use and Open Content” at the seventh annual Festival of Art History, along with speakers from the Paul Mellon Center for Studies in British Art (UK), the J. Paul Getty Trust, and the French Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art.

The College Art Association has been invited to speak about its Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts at two conferences taking place in France in early June. On June 4 in Fontainebleau, executive director Hunter O’Hanian will participate in a session on “Fair Use and Open Content” at the seventh annual Festival of Art History, along with speakers from the Paul Mellon Center for Studies in British Art (UK), the J. Paul Getty Trust, and the French Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art.

Two days later, on June 6, Hunter will join Peter Jaszi, lead principal investigator on the Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts, in Paris to speak at a session on fair use during the annual conference of ICOM Europe. They will be joined by speakers from England, France, and Germany, to discuss “Copyright Flexibilities in the US and EU: How Fair Use and Other Flexibilities are Helping Museums to Fulfill their Mission.”

Both conferences provide opportunities for CAA to share its work on fair use with EU visual arts professionals. Though this feature of copyright law is virtually unique to the United States, there is increasing interest in Europe to provide greater access to copyrighted materials, especially in the cultural sectors of these countries. Travel costs for CAA’s participation are underwritten by a generous grant from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation.

Letter from Melbourne: An Exhibition at the Victorian College of the Arts Tackles Contested Lands and Landscape

posted by Sean Lowry, Head of Critical and Theoretical Studies,Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne, Australia — April 27, 2017

We live in a world in which deeply contested perceptions of time and place coexist on lands shared by diverse populations. The unresolved politics of land that confront Indigenous cultures in Australia are a prime example of how such contestations continue to play out in a postcolonial context. Such tensions are particularly apparent when contrasting radically divergent artistic and historical representations of landscape. Australia is a vast and ancient continental landmass upon which a little over two centuries of colonization has savagely interrupted 50,000 years of continuous human culture expressed through over 500 distinct collective nominations. Presence, an ambitious exhibition curated by David Sequeira in the Margaret Lawrence Gallery at the Victorian College of the Arts (VCA), University of Melbourne (March 3–April 1, 2017), entered this seemingly inexpressible contestation with a curatorial strategy that provisionally marked out something of the possibility of aggregating these radically disparate understandings. As this text will attempt to demonstrate, Sequeira, in bringing otherwise ineffably distinct representations of the Australian landscape together, implicitly suggested that violently incompatible senses of time and place might indeed share space—and possibly even begin to communicate with one another.

Figures 1 and 2 show the gallery installation with Michael Riley’s film presented in the center. The two images from the film depict different contemporary perspectives of a land occupied by Indigenous cultures for tens of thousands of years. The smaller paintings installed on the perimeter wall are by well-known Australian artists who are all alumni of the Victorian College of the Arts upon the occasion of its 150-year celebration (see Figures 3–8 below).

Upon entering the dramatically darkened gallery, the viewer encountered a series of small uncaptioned spot-lit paintings by some of the VCA’s most distinguished alumni. These works appeared to be floating like a constellation of celestial objects around a large moving image projection at the center of the exhibition space. Sequeira strategically positioned Empire, a film by the late Indigenous Australian artist Michael Riley, at the heart of this carefully considered installation of historical and contemporary landscape paintings.

Figure 3: Eugene Von Guérard, From below the Lighthouse, Cape Shanck, Victoria, 1873, oil on paper on board, 9.7 x 12.4 in. (photograph provided by the Wilbow Collection)

Figure 4: Frederick McCubbin, At Macedon, 1913, oil on canvas 20.4 x 24.1 in. (photograph provided by the Wilbow Collection)

Figure 5: Fred Williams, Hillside III, 1968, oil on canvas, 24 x 26 in. (photograph provided by the Heidi Victoria Collection)

Contextualizing work by Eugene Von Guerard, Frederic McCubbin, Fred Williams, Clarice Beckett, Louise Hearman, and Rick Amor with that of Riley, Sequeira seductively stipulated that the viewer become mindful of Indigenous understandings of landscape that existed for 50,000 years prior to the VCA’s own 150-year history.

Figure 6: Clarice Beckett, Half Moon Bay, undated, oil on board, 11.2 x 15 in. (photograph provided by Rosalind Hollinrake and Niagara Galleries)

Figure 7: Louise Hearman, Untitled #480, 1997, undated, oil on composition board, 27 x 21 in. (photograph provided by the Wilbow Collection)

Figure 8: Rick Amor, Summer Morning Lucerne Crescent Alphington, 2012, oil on canvas, 20.1 x 15.9 in., Courtesy the artist and Niagara Galleries.

Not inconsequentially, Riley was not a VCA alumnus. This was a brave and deliberate curatorial gesture on the part of Sequeira to mark the occasion of the institution’s 150-year celebrations: “For most of its 150-year history, the Victorian College of the Arts ignored Indigenous Australian culture and art practices. I wanted the large-scale projection (including its soundtrack) by Indigenous artist Michael Riley to be the filter through which the other works of art are perceived.”[1]

Significantly, the deliberately modestly sized selection of paintings orbiting Riley’s intermittently expansive and forensic visual meditation upon the impact of colonialism and Christian missionary activities on Australian Aboriginal land and culture, were subsequently drawn inward to perform in concert with the deeply melancholic musical score by composer Antony Partos and performed by the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra that accompanied Riley’s filmic essay. Sound is clearly an important part of Sequeira’s matrix of considerations. Considered together with the lighting design, we can see why Sequeira describes a “multi-sensory approach” as “critical in the process of generating new [historical] resonances.” Already an ode to the simultaneous expansiveness and minutiae of Australian landscape, once experienced on a big screen at the center of Sequeira’s installation, Empire commanded a hitherto unconsummated presence (especially when considered in comparison with earlier broadcast and exhibition presentations).

It was clear that none of these works had ever been exhibited like this before. Consequently, one of the most marked features of this exhibition was the conspicuous visibility of Sequeira’s curatorial voice. Moreover, it was not a stretch to reimagine this poetic exploration of new possibilities in selection and display as an installation by an artist rather than the work of a curator. Here, networks of relations marked between very different artistic materializations and senses of placemaking clearly instantiated the space of the exhibition itself as medium. In demonstrating profound new ways in which very different conceptions of landscape might sing together, and by extension, how accepted lineages of art history might in turn learn to incorporate understandings of Indigenous Australian art and culture, Sequeira created a work of art that far exceeded a sum of its parts. Although Sequeira understands his responsibilities to these histories “as part of a bigger commitment as an artist,” he also recognizes that curatorship demands very particular responsibilities. Despite the fact that we might reimagine the exhibition as an installation by Sequeira the artist, Sequeira the curator nevertheless understood that this would invariably “reflect a different style of authorship.” Interestingly, he appeared at once emboldened and troubled when asked to consider the exhibition as an installation by him as an artist. Clearly, Sequeira necessitates that these activities remain ontologically separate—for as Ruth Noack put it in 2015—just as “the other of the artist as curator is the curator,” it is also apparent that “the other of the curator as artist is the artist.”[2]

Importantly, Sequeira sees his “own subjectivity is a departure point for the exploration of other histories.” As a “middle-aged gay Indian born Australian man,” he sees his “subjectivity as an access to the disclosure of new understandings of art and art history.” For Sequeira, “creating opportunities for the revelation of new or previously undistinguished facets of history is integral to this process.” In order to facilitate this process, he first considers “selection and display strategies used in the construction mainstream histories” and then begins to develop alternative formats that suggest “new resonances within both individual works of art and a group as a whole.” When asked to imagine this exhibition as the first in a series, and that its next instantiation might be in the United States, Sequeira excitedly described one possible scenario:

the compelling video work of Mohawk artist Alan Michelson could be a potent context for re thinking American landscape painting. For example, set within a suite of small historic and contemporary landscape paintings by artists such as Thomas Cole, Josephine Chamberlin Ellis, Frederick Church, Georgia O’Keefe [sic], Alma Thomas, Andrew Wyeth, Michelson’s large scale projection (on a screen of turkey feathers), Mesprat, 2001 could expand the understandings of consumerism, spirituality, the sublime, environmentalism and ownership associated with considerations of landscape.

From exhibitions to nation states, delineations of place are destined to be dynamic and temporary. Unlike space, which possesses abstract physical and formal properties, the value of place is socially constructed. Against a backdrop of inevitable change, art performs both a mnemonic and a transitive role. This role is perhaps most apparent when art is experienced as a dynamic constellation of elements rather than as ossified objects. Although the idea of landscape is central to the sense of being in Australia, it can clearly evoke complex and unresolved historical and political tensions. Artists that deal with landscape as subject are by default connected to these tensions. The island continent of Australia is at once a timeless geological formation and a historically layered series of cultural projections. For a mere blip in historical time, a new nation has been superimposed over an ancient geological formation and accompanying appropriated nations. Landscape, like painting, is a register of gestures enacted upon a surface. Marks, together with conspicuous omissions and evacuations, can imply both desolation and new possibilities. Painting, like film, is a fertile ground upon which to stage a dynamic play between registers of information and space for the imagination to flourish. By suggesting new possibilities through the poetic play of disparate representations of landscape, and at the same time reminding the viewer that full comprehension is impossible, Sequeira has created an evocative vehicle with which to reimagine absence and presence.

[1] David Sequeira, email conversation with the author, March 31, 2017. All subsequent quotations by Sequeira are from email conversations that took place between March 31 and April 3, 2017.

[2] Ruth Noack, “The Curator as Artist?” (symposium presentation, Central Saint Martins, London, November 10, 2012). See http://afterall.org/online/artist-as-curator-symposium-curator-as-artist-by-ruth-noack/.

2017 CAA-Getty International Program Reunion

posted by CAA — November 10, 2016

CAA Names Recipients for

2017 CAA-Getty International Program Reunion

Celebrating five successful years of the CAA-Getty International Program, the College Art Association (CAA) is pleased to announce the selection of twenty alumni to participate in a reunion program during the 2017 CAA Annual Conference, taking place in New York City from February 15-18. Funded by a generous grant from the Getty Foundation, the alumni will join distinguished scholars from the United States for a series of four conference sessions on international topics in art history.

The twenty alumni chosen for the reunion program will travel to the Annual Conference from home countries as varied as Malaysia, Cameroon, and Argentina, to name a few. As scholars, their work encompasses an equally wide spectrum, including topics such as international modernism, Islamic architecture in Southeast Asia, and contemporary aesthetics and art. Connecting the diverse mix of cultural, environmental, and scholarly backgrounds is central to the mission of CAA.

2017 CAA-Getty International Program Reunion participants

Since 2012, the Getty Foundation has supported CAA in bringing between fifteen and twenty scholars from countries around the world to its Annual Conference. Open to professors of art history, curators, and artists who teach art history, the program boasts ninety alumni from forty-one countries. Many scholarly collaborations and exchanges have ensued, both between these international scholars and North American members of CAA, and among the international scholars themselves. The 2017 reunion will celebrate these accomplishments and deepen ties with these international scholars.

“It is a pleasure to work with CAA on the international program, which has brought so many interesting scholars from all over the world to the United States for the Annual Conference,” said Deborah Marrow, director of the Getty Foundation. “We have learned so much from the scholars’ participation and are delighted to support the upcoming reunion program. Congratulations to CAA and these remarkable alumni.”

This past summer, alumni helped to shape the reunion plans, working with members of CAA’s International Committee. Using CAA Connect, CAA’s new digital discussion platform, committee members Elisa Mandell (California State University, Fullerton), Judy Peter (University of Johannesburg, South Africa), and Miriam Paeslack (University of Buffalo), in consultation with committee chair Rosemary O’Neill (Parsons The New School for Design), moderated an online discussion about a wide range of international issues, looking for ideas that would make particularly good topics for the four conference sessions to be held in February. Linked under the heading “Global Conversations,” the daily sessions will address the following topics: “Decolonizing the Curriculum, “Dominant Ideologies and Political Trauma,” “The Trouble with (the Term) Art,” and “Transnational Collaborations and Interdisciplinarity.”

Joining the alumni at these sessions will be four members (or former members) of the National Committee for the History of Art (NCHA). Since it began, the CAA-Getty International Program has benefitted from the participation of NCHA members, both as speakers and hosts to the international colleagues. This year, Frederick Asher (University of Minnesota), Michael Ann Holly (Research and Academic Program, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute), Mary Miller (Yale University), and David Roxburgh (Harvard University) are each moderating one of the Global Conversations, adding their expertise to the discussions.

CAA is grateful to the Getty Foundation for its ongoing support of this program, and to the members of CAA’s International Committee and NCHA who have contributed their time and expertise to making the program a success.

About CAA

The College Art Association (CAA) is dedicated to providing professional services and resources for artists, art historians, and students in the visual arts. CAA serves as an advocate and a resource for individuals and institutions nationally and internationally by offering forums to discuss the latest developments in the visual arts and art history through its Annual Conference, publications, exhibitions, website, and other programs, services, and events. CAA focuses on a wide range of advocacy issues, including education in the arts, freedom of expression, intellectual-property rights, cultural heritage and preservation, workforce topics in universities and museums, and access to networked information technologies. Representing its members’ professional needs since 1911, CAA is committed to the highest professional and ethical standards of scholarship, creativity, criticism, and teaching. Learn more about CAA at www.collegeart.org.

About the J. Paul Getty trust and the Getty Foundation

The J. Paul Getty Trust is an international cultural and philanthropic institution devoted to the visual arts that includes the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Getty Research Institute, the Getty Conservation Institute, and the Getty Foundation. The J. Paul Getty Trust and Getty programs serve a varied audience from two locations: the Getty Center in Los Angeles and the Getty Villa in Pacific Palisades.

The Getty Foundation fulfills the philanthropic mission of the Getty Trust by supporting individuals and institutions committed to advancing the greater understanding and preservation of the visual arts in Los Angeles and throughout the world. Through strategic grant initiatives, the Foundation strengthens art history as a global discipline, promotes the interdisciplinary practice of conservation, increases access to museum and archival collections, and develops current and future leaders in the visual arts. It carries out its work in collaboration with the other Getty Programs to ensure that they individually and collectively achieve maximum effect. Additional information is available at www.getty.edu/foundation.

For more information about the CAA-Getty International Program contact Janet Landay, Project Director.

South African Diary

posted by Janet Landay, Project Director, CAA-Getty International Program — October 18, 2016

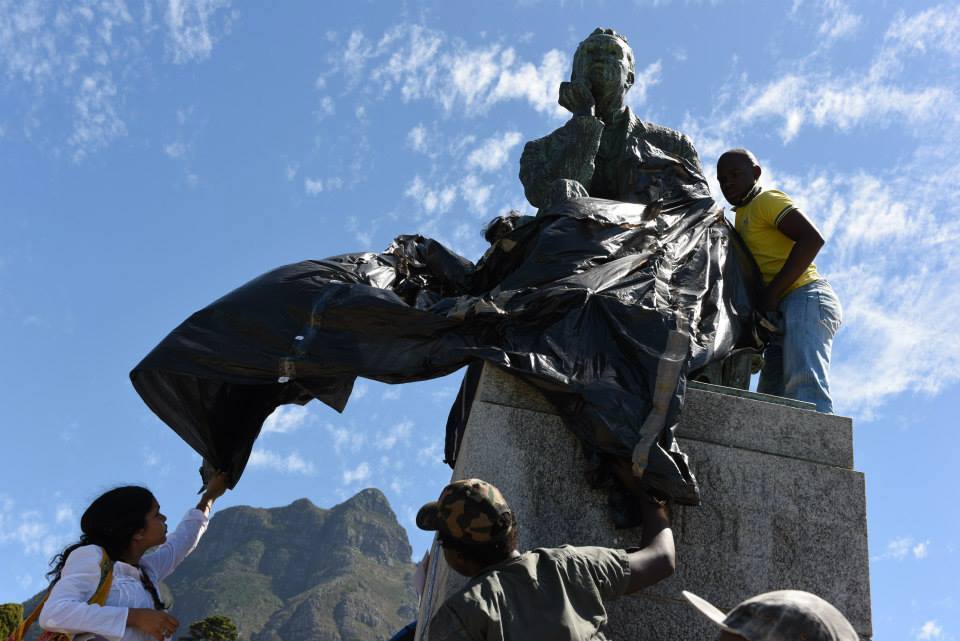

Rhodes Must Fall, downloaded from https://www.facebook.com/RhodesMustFall/photos

Posted by Janet Landay, Project Director, CAA-Getty International Program (for CAA News and the International Desk)

This summer I was invited by two alumni of the CAA-Getty International Program—Karen von Veh and Federico Freschi, both from the University of Johannesburg—to attend the 31st Annual Conference of the South African Visual Arts Historians (SAVAH). In the first five years of the CAA-Getty program, seven art historians from South Africa have participated—the most from any single country. Their strong presence at CAA’s Annual Conferences suggests a robust community of scholars, and I was eager to witness it firsthand.

In late July I flew to Johannesburg, where I met up with Rosemary O’Neill, associate professor of art history at Parsons the New School of Design and chair of CAA’s International Committee, who was also participating in the conference. On the day we arrived there was an intense thunderstorm followed by large hail. Our hosts, Karen von Veh and her husband Bengt, assured us that this was not normal for a Johannesburg winter. By the next day the sun had come out, and it remained sunny and pleasantly cool for the rest of our stay.

The weather may well serve as a metaphor for the abnormal state of affairs in South Africa: unusually stormy one day, seemingly calm the next. Twenty-two years after the end of apartheid, the country, and especially its university system, is in an enormous state of flux. Since March 2015, students have militated against South Africa’s twenty-three government-funded universities in two related protests. The first was Rhodes Must Fall, which demanded the removal of a sculpture of Cecil Rhodes, the embodiment of British racist colonial imperialism, from the University of Cape Town (UCT), and included the broader demand for decolonizing the university system, including curricula, language of instruction, and workers’ rights.

In October 2015 came Fees Must Fall, prompted by the announcement of a steep increase in fees at the University of Witwatersrand. Both movements have had successes: the UCT sculpture of Rhodes was removed, and many other public symbols of colonial rule have been taken down or defaced; students at Rhodes University persuaded authorities to consider renaming the school; and the government announced there would be no tuition increase for 2016. (This issue is being debated again, as increases for 2017 have elicited renewed protests.) These events are taking place at the same time that the government is reducing financial support for the universities.

Art, Design and Architecture Building at the University of Johannesburg, downloaded from university website, https://www.uj.ac.za/faculties/fada/Pages/Facilities.aspx

This was the context for SAVAH’s Annual Conference, as approximately sixty professors of art history, visual culture, and studio art gathered at the University of Johannesburg for three days of papers and discussion. Organized by Federico Freschi (executive dean), Brenda Schmahmann (research professor), and Karen von Veh (associate professor), all from the Faculty of Art, Design, and Architecture at the University of Johannesburg, the conference was titled “Rethinking Art History and Visual Culture in a Contemporary Context.” The ongoing crisis in higher education charged the sessions and discussions with particular intensity. The subjects addressed, whether historical, pedagogical, or political, were not chosen solely for theoretical considerations; speakers were seeking practical solutions to the immediate challenges they face as scholars and teachers in post-apartheid South Africa.

An underlying theme of the conference—how can art history be relevant and useful to scholars and students at this charged moment in time?—was a subtext in Steven Nelson’s eloquent keynote address. In a discussion of works by Houston Conwill, Moshekwa Langa, and Julie Mehretu, Nelson—a professor of African and African American art and director of the Center for African Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles—considered how the use of mapping and geography by these artists has reshaped our understanding of African ancestry, notions of diaspora, and urban spaces. The weaving of past and present, continental Africa and the African diaspora, and art-historical analyses of traditional forms and new media exemplified the ongoing relevance of the art-historical discipline to understanding contemporary art and culture.

Session topics during the two-day conference ranged from “International Curatorial Practices” to “The Politics of Display in South Africa” and “Decolonizing Education (Parts I and II)” to “Postcolonialism beyond South Africa.” Alison Kearney, a lecturer at the University of the Witwatersrand, delivered a paper titled “Art history is dead—long live art history!” in which she explored the deeper meaning of decolonizing the university, beyond the tokenistic call for more black authors and artists. This decolonization will lead to “the inevitable end of art history” and a return to the work of art and an interdisciplinary approach as a “deliberate means of destabilizing a single disciplinary gaze.” Fiona Siegenthaler, a senior lecturer at the Institute for Social Anthropology, Universität Basel, compared the call for decolonization in South Africa to the one in Uganda. Because the population in Uganda is overwhelmingly black, the call for decolonization has little to do with the racial profile of its teachers or students. Rather, the country is focused on rewriting curricula to be more relevant to their students’ lives. Both countries, she stated, are skeptical about the hegemony of neoliberalism as a form of neocolonialism, on the one hand, and the need for access to international contemporary art, art institutions, art markets and funding organizations, on the other.

Several speakers explored alternative approaches to current studies in South African art history. Lize van Robbroeck, from the University of Stellenbosch, spoke about “settler colonial studies” and a multinational research project she is part of that examines settler life in five former British dominions: New Zealand, South Africa, Canada, Australia, and the United States. The cultural, economic, and political circumstances in each of these colonies, in spite of particular dynamics in each, created comparable artistic products in the early to mid-twentieth century. The group’s research suggests that the demands to establish national art canons in each of these locations led to a corresponding art-historical neglect of the striking cross-national similarities in the art produced by artists in each place.

A paper by Jackson Davidow, from the Department of Architecture at MIT, called on the discipline of art history to enlarge its approach to “traverse geographies, temporalities, environments, and communities.” He made the case by discussing a global history of AIDS activist art, which must still be historically contextualized within local landscapes. His paper posed a crucial question to contemporary scholars: “How can global art histories work to decolonize and deconstruct the practices of our discipline rather than perpetuate its oppressive structuring?”

The conference ended with two papers from other humanities disciplines. The first one, by Brett Pyper from the University of the Witwatersrand, was about curating indigenous musical performances at the National Arts Festival in Grahamstown. Leana van der Merwe, of the University of Pretoria, delivered the second, which was about an “African” feminist philosophy of art. Many of the conference papers will be published in an upcoming issue of De Arte, a peer-reviewed South African journal on visual arts, art history, and art criticism.

The SAVAH conference was not the only significant art event taking place in Johannesburg during my visit. The meetings coincided with a historic exhibition held downtown at the Standard Bank Gallery: the first-ever presentation on the African continent of paintings and works on paper by Henri Matisse.

Henri Matisse, The Horse, the Rider and the Clown,1947, fifth plate of the book Jazz, Musée Matisse in Le Cateau-Cambrésis

Juxtaposed against the topic of the conference—rethinking art history in a contemporary context—this major exhibition provided another bellwether of the state of art history in South Africa. The absence of Matisse exhibitions in the entire continent until now can partially be explained by practical reasons related to insufficient resources (shipping and insurance costs, museum-quality exhibition spaces, etc.), but it is also likely due, in part, to a reluctance or lack of interest on the part of European and American collections and African-based organizers to bring the artist’s work to African audiences, in spite of Matisse’s great interest in African art. During my visit to South Africa, I was struck by the lack of Western art displayed in the museums, with the exception of a small collection on view at the National Museum in Cape Town. Little access to this art is yet another challenge for professors of art history, and it must relate to the absence of Matisse exhibitions as well. Why should South Africans be interested in his work if, for many, he is an unknown, dead white European artist? There is an audience for Matisse in South Africa, including the well-educated professional class and an active, sophisticated group of collectors who support a growing number of commercial galleries. There is also a vibrant community of artists in South Africa whose work characteristically draws on indigenous artistic traditions as well as global art. In spite of the limited audience—or perhaps because of it—a Matisse exhibition in Johannesburg is an important event, a major step toward broadening an appreciation of global art and its history.

In Johannesburg, the Matisse exhibition was the fourth in a series of presentations at the Standard Bank Gallery of works by twentieth-century modern European masters. Previous projects focused on Mark Chagall, Joan Miró, and Pablo Picasso. Through the curatorial efforts of Federico Freschi and Patrice Deparpe, director of the Musée Matisse in Le Cateau-Cambrésis, the exhibition Henri Matisse: Rhythm and Meaning was on view at the Standard Bank Gallery from July 13 to September 17, 2016. It included significant paintings, drawings, collages, and prints covering all the dominant themes in the artist’s oeuvre, from his early Fauvist years to the paper cut-outs produced in the last years of his life. As Freschi noted in introductory remarks, “Of particular interest to South African audiences is the inspiration Matisse took from African and other non-Western art forms during the early 1900s while struggling to find a new visual language to express the particular experience of the new, modern age.”

Patrice Deparpe, Director of the Musée Matisse in Le Cateau-Cambrésis, in the exhibition Henri Matisse: Rhythm and Meaning, downloaded from website of the Embassy of France in South Africa.

To open the SAVAH conference, a lecture, gallery talk and reception for the exhibition was held the evening before the conference proceedings began. Rosemary O’Neill presented a thought-provoking lecture titled, “Henri Matisse: Fluid Memory, Embodied Signs.” Her paper considered aspects of Matisse’s work in relation to the construct of memory, time, and intuitive expression, as well as the influence of the ideas of philosopher Henri Bergson. In discussing Jazz, O’Neill identified ways in which his Tahitian memories from 1930, as well as his own cultural context and artistic trajectory, resulted in the realization of the innovative process and expression soon evident in Matisse’s late cut-outs; their importance in relation to a revival of the decorative impulse in postwar France; and their analogous relationship to poetic and musical phrasing—that is, a system of ensemble signs—as articulated in the writings of the poet Louis Aragon. Freschi’s subsequent gallery talk elaborated on Matisse’s exploration of African modes of representation in his early works; then, calling special attention to the series of prints that comprise the artist’s book, Jazz, he emphasized the influence of his travel to Tahiti and the archipelago islands that appear in his use of patterns and rhythms, ephemeral materials, and a conceptual rather than perceptual approach to image making.

For an American visitor, the conference and exhibition provided much food for thought. It was impossible to ignore similarities in the dissatisfactions of university students in both countries. Like their South African counterparts, U.S. students are demanding a greater diversity of voices in the curriculum, on the faculty, and in the administrations of colleges and universities. In both countries, growing complaints about racial inequality and ties to apartheid or slavery have resulted in important, if mostly symbolic, changes. At about the same time that South African authorities were removing sculptures of Cecil Rhodes and suspending tuition hikes, leaders at Georgetown University announced efforts to make amends for its complicity in the nation’s slave trade, including preferential admissions for descendents of slaves sold in 1838 by Maryland Jesuits to stave off the college’s bankruptcy. Other schools, such as Brown University, Harvard University, Emory University, and the University of Virginia, have made their historical ties to slavery public and announced plans such as renaming buildings, creating racial justice programs, and erecting memorials acknowledging their ties to the transatlantic slave trade.

[Just last week in New York City, as part of an anti-Columbus Day protest, a diverse group of protesters, united under the banner “Decolonize This Place,” demanded the removal of an equestrian sculpture of Theodore Roosevelt (flanked on either side by a Native American and an African American) at the entrance to the American Museum of Natural History. The crowd included activists from the Black Lives Matter, Indigenous rights, and other labor and social justice movements. Calling it “the most visible symbol of white supremacy in New York,” the group also called for “decolonizing of the museum,” citing specific exhibits within the museum that highlight its history of white supremacy and colonialism. The demonstration was one of many across the country protesting the continued observance of Columbus Day, demanding that it be replaced by Indigenous People Day.]

From my vantage point as a participant at the SAVAH conference, the most striking similarity between the two countries was the paucity of people of color among art history professors and students. This was the great unspoken problem at the conference, evidenced by the prevalence of white faculty and students at a gathering focused on decolonization, art and activism, and keeping art history relevant. There were a small number of people of color at the conference among both speakers and attendees, but much like at a CAA Annual Conference, the dominant color was white. The answer is not, as some radical South African students demand, to rid the curriculum of all European content, or to replace all white professors with black ones; rather, it lies both in a multiplicity of voices and a questioning of assumptions rooted in the foundational texts of the field. Solving this problem may be the greatest challenge to art history’s relevance, even as progress is made alongside the slow path to racial equality.

South Africa is sometimes called a Petri dish for studying race relations. Only twenty-two years away from government-enforced racism, the country’s efforts in building a democratic, racially equal society offer many lessons about effective and less effective ways to accomplish radical change. The art historians I met in Johannesburg have created a vital community in which to study and struggle with these lessons. They are keeping the discipline of art history alive and relevant to the cultural and political challenges they face. But how they do it may provide important guidelines for scholars in the United States. In spite of numerous differences between the two countries—especially in scale, resources, and history—both South African and U.S. art historians are grounded in the same antecedents. How to retain the strengths of a discipline born in nineteenth-century Germany while stretching its geographic parameters to include all cultures is a challenge we all face.

Comment on this article in the Diversity in the Arts community on CAA Connect.

CIHA 2016 in Beijing

posted by CAA — August 15, 2016

The thirty-fourth World Congress of Art History, organized by the Comité International d’Histoire de l’Art (CIHA), will take place in Beijing, China, from September 15 to 22, 2016. Art and cultural historians from all over the world, and from a vast cross-section of disciplines and fields of professional interest, will discuss the ways of seeing, describing, analyzing, and classifying works of art. As the American affiliate to CIHA, the National Committee for the History of Art (NCHA), a group with strong institutional ties to CAA, is happy to encourage any and all interested art historians to attend.

The thirty-fourth World Congress of Art History, organized by the Comité International d’Histoire de l’Art (CIHA), will take place in Beijing, China, from September 15 to 22, 2016. Art and cultural historians from all over the world, and from a vast cross-section of disciplines and fields of professional interest, will discuss the ways of seeing, describing, analyzing, and classifying works of art. As the American affiliate to CIHA, the National Committee for the History of Art (NCHA), a group with strong institutional ties to CAA, is happy to encourage any and all interested art historians to attend.

The congress’s theme is “Terms.” Topics are divided into twenty-one sections to enable comparisons among different interpretations, definitions, and methods within art history. Each panel will comprise a program reflecting CIHA’s commitment to the idea of diversity, which should allow talks on different genres, epochs, and countries to be brought together. The congress uses the word “Terms” to draw a wide range of case studies.

The theme for the Beijing 2016 is the logical counterpart to the previous rubric, “The Challenge of the Object,” which was addressed at the Nuremberg 2012 CIHA Congress in Germany. In Beijing, it is a matter of questioning the words, the definitions, and the very concepts used to study art by different scientific traditions with this essential question: How can the methodology of our discipline be enriched by being conscious of the diversity of terms and approaches to art?

The 2016 congress will analyze different concepts of art in diverse cultures and strive to achieve three goals. The first one is to respond to the latest development of art history as a global discipline. The second is to explore art through different terms that underline its relationship to respective cultural frameworks, and the disparities between different cultures in various periods throughout history. The third goal is to gain a more comprehensive understanding of art as an essential part of human culture.

CIHA traces its roots back to the 1930s, when it was officially founded at the Brussels Congress. The organization has now vastly exceeded its original Euro-American emphasis and currently has national chapters on every continent. Next month’s meeting will be the organization’s first conference in China. In addition to the international gathering held every four years, CIHA also sponsors specific thematic art-history conferences such as “New Worlds: Frontiers, Inclusion, Utopias” in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, which took place in August 2015.

CAA Signs Letter Supporting Turkish Academic Freedom

posted by CAA — August 09, 2016

CAA has signed onto the letter reprinted below, written by the Middle East Studies Association (MESA) on July 21, 2016, and signed by dozens of organizations. To read the full list of signatories, please visit the MESA website.

Threats to Academic Freedom and Higher Education in Turkey

The above listed organizations collectively note with profound concern the apparent moves to dismantle much of the structure of Turkish higher education through purges, restrictions, and assertions of central control, a process begun earlier this year and accelerating now with alarming speed.

As scholarly associations, we are committed to the principles of academic freedom and freedom of expression. The recent moves in Turkey herald a massive and virtually unprecedented assault on those principles. One of the Middle East region’s leading systems of higher education is under severe threat as a result, as are the careers and livelihoods of many of its faculty members and academic administrators.

Our concern about the situation in Turkish universities has been mounting over the past year, as Turkish authorities have moved to retaliate against academics for expressing their political views—some merely signing an “Academics for Peace” petition criticizing human rights violations.

Yet the threat to academic freedom and higher education has recently worsened in a dramatic fashion. In the aftermath of the failed coup attempt of July 15–16, 2016, the Turkish government has moved to purge government officials in the Ministry of Education and has called for the resignation of all university deans across the country’s public and private universities. As of this writing, it appears that more than 15,000 employees at the education ministry have been fired and nearly 1,600 deans—1,176 from public universities and 401 from private universities—have been asked to resign. In addition, 21,000 private school teachers have had their teaching licenses cancelled. Further, reports suggest that travel restrictions have been imposed on academics at public universities and that Turkish academics abroad were required to return to Turkey. The scale of the travel restrictions, suspensions, and imposed resignations in the education sector seemingly go much farther than the targeting of individuals who might have had any connection to the attempted coup.

The crackdown on the education sector creates the appearance of a purge of those deemed inadequately loyal to the current government. Moreover, the removal of all of the deans across the country represents a direct assault on the institutional autonomy of Turkey’s universities. The replacement of every university’s administration simultaneously by the executive-controlled Higher Education Council would give the government direct administrative control of all Turkish universities. Such concentration and centralization of power over all universities is clearly inimical to academic freedom. Moreover, the government’s existing record of requiring university administrators’ to undertake sweeping disciplinary actions against perceived opponents—as was the case against the Academics for Peace petition signatories—lends credence to fears that the change in university administrations will be the first step in an even broader purge against academics in Turkey.

Earlier this year, it was already clear that the Turkish government, in a matter of months, had amassed a staggering record of violations of academic freedom and freedom of expression. The aftermath of the attempted coup may have accelerated those attacks on academic freedom in even more alarming ways.

As scholarly organizations, we collectively call for respect for academic freedom—including freedom of expression, opinion, association, and travel—and the autonomy of universities in Turkey, offer our support to our Turkish colleagues, second the Middle East Studies Association’s “call for action” of January 15, request that Turkey’s diplomatic interlocutors (both states and international organizations) advocate vigorously for the rights of Turkish scholars and the autonomy of Turkish universities, suggest other scholarly organizations speak forcefully about the threat to the Turkish academy, and alert academic institutions throughout the world that Turkish colleagues are likely to need moral and substantive support in the days ahead.

Note

Organizations wishing to be included as signatories on the above statement should contact Amy Newhall at amy@mesana.org.