CAA News Today

Announcing the 2020 CAA-Getty International Program Participants

posted Oct 07, 2019

CAA-Getty International Program Participating Alumni (left to right) Chen Liu, Nazar Kozak, Katarzyna Cytlak, Nadhra Khan, and Sarena Abdullah at the 2019 Annual Conference in New York. Photo: Ben Fractenberg

We’re pleased to announce this year’s participants in the CAA-Getty International Program. Now in its ninth year, this international program supported by the Getty Foundation will bring fifteen new participants and five alumni to the 2020 Annual Conference in Chicago, Illinois.

The participants—professors of art history, curators, and artists who teach art history—hail from countries throughout the world, expanding CAA’s growing international membership and contributing to an increasingly diverse community of scholars and ideas. This year we are adding participants from four countries not included previously—Bolivia, Saudi Arabia, Côte d’Ivoire, and Singapore—bringing the total number of countries represented by the program to fifty. Selected by a jury of CAA members from a highly competitive group of applicants, the participants will receive funding for travel expenses, hotel accommodations, conference registration, CAA membership, and per diems for out-of-pocket expenditures.

At a one-day preconference colloquium, to be held this year at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, the fifteen new participants will discuss key issues in the international study of art history together with five CAA-Getty alumni and several CAA members from the United States, who also will serve as hosts throughout the conference. The preconference program will delve deeper into subjects discussed during last year’s program, including such topics as postcolonial and Eurocentric legacies, interdisciplinary and transnational methodologies, and the intersection of politics and art history.

This is the third year that the program includes five alumni, who provide an intellectual link between previous convenings of the international program and this year’s events. They also serve as liaisons between CAA and the growing community of CAA-Getty alumni. In addition to serving as moderators for the preconference colloquium, the five alumni will present a new Global Conversation during the 2020 conference titled Things Aren’t Always as they Seem: Art History and the Politics of Vision.

The goal of the CAA-Getty International Program is to increase international participation in the organization’s activities, thereby expanding international networks and the exchange of ideas both during and after the conference. CAA currently includes members from sixty countries around the world. We look forward to welcoming the following participants at the next Annual Conference in Chicago.

2020 Participants in the CAA-Getty International Program

Irene Bronner, Senior Lecturer, NRF South African Research Chair in South African Art and Visual Culture, University of Johannesburg, South Africa

Eiman Elgibreen, Assistant Professor of Art History, The Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Daria Jaremtchuk, Associate Professor of Art History, University of São Paulo, Brazil

Ganiyu Jimoh, Lecturer, University of Lagos, Nigeria, and Postdoctoral Fellow, Arts of Africa and Global Souths research program, Department of Fine Art, Rhodes University, South Africa

Mariana Levytska, Research Associate, Department of Art Studies, Ethnology Institute, UNAS (National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine)

Daniela Lucena, Head of Research Team, National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET), University of Buenos Aires, Argentina

Ali Mahfouz, Director, Mansoura Storage Museum, Ministry of Egyptian Antiquities, Egypt

Priya Maholay-Jaradi, Convenor, Art History, National University of Singapore

Valeria Maria Paz Moscoso, Academic Coordinator and Advisor, Universidad Catolica Boliviana San Pablo, La Paz, Bolivia

Daria Panaiotti, Curator of Photography and Research Associate, The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Aleksandra Paradowska, Assistant Professor, University of Fine Arts, Poznań, Poland

Saurabh Tewari, Assistant Professor, School of Planning and Architecture, Bhopal, India

Giuliana Vidarte, Chief Curator and Head of Exhibitions, Museum of Contemporary Art of Lima and Peruvian University of Applied Sciences, Peru

Julia Waite, Curator of New Zealand Art, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, New Zealand

Jean-Arsène Yao, University Félix Houphouët-Boigny, Côte d’Ivoire

Participating Alumni

Abiodun Akande, Senior Lecturer, University of Lagos, Nigeria

Pedith Chan, Assistant Professor of Cultural Management, Chinese University of Hong Kong

Iro Katsaridou, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, Museum of Byzantine Culture, Thessaloniki, Greece

Cristian Emil Nae, Associate Professor, George Enescu National University of Arts, Iasi, Romania

Nora Veszpremi, Research Associate, Continuity/Rupture: Art and Architecture in Central Europe 1918–1939 (CRAACE), Masaryk University in Brno, Czech Republic

Carlos Rene Pacheco and Anh-Thuy Nguyen

posted Oct 07, 2019

The weekly CAA Conversations Podcast continues the vibrant discussions initiated at our Annual Conference. Listen in each week as educators explore arts and pedagogy, tackling everything from the day-to-day grind to the big, universal questions of the field.

CAA podcasts are on iTunes. Click here to subscribe.

This week, Carlos Rene Pacheco and Anh-Thuy Nguyen discuss preparing MFA graduates to be educators/faculty members.

Carlos Rene Pacheco is a photographer and new media artist and he currently resides in Fargo, North Dakota where he has taught courses in Photography, Contemporary Art Theory, and Professional Practices in the Arts as an Assistant Professor of Art at Minnesota State University Moorhead.

Anh-Thuy Nguyen is a Tucson-based multi-media/transdisciplinary artist, whose work spans from photography, video, and installation to performance art, and she is the head of the photography program at Pima Community College, Tucson, Arizona.

New in caa.reviews

posted Oct 04, 2019

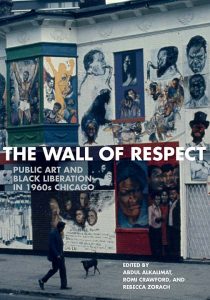

Sarah Hollenberg reviews The Wall of Respect: Public Art and Black Liberation in 1960s Chicago, edited by Abdul Alkalimat, Romi Crawford, and Rebecca Zorach. Read the full review at caa.reviews.

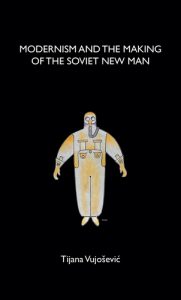

Kristin Romberg discusses Tijana Vujošević’s book Modernism and the Making of the Soviet New Man. Read the full review at caa.reviews.

Risham Majeed writes about the exhibition Agents of Faith: Votive Objects in Time and Place, curated by Ittai Weinryb. Read the full review at caa.reviews.

Deadline Extended! Participate in ARTexchange at CAA 2020

posted Oct 04, 2019

Originally formatted as a pop-up exhibition and meet-up event for artists and curators, ARTexchange provides an opportunity for artists to share their work and build affinities with other artists, historians, curators, and cultural producers at the Annual Conference.

This year, instead of a one-time event, ARTexchange invites artists to lead participatory projects and/or workshops over the duration of the conference with a culminating public reception on Friday, February 14, from 7-8:30 pm.

CAA’s Services to Artists Committee, in collaboration with the Hokin Project, a gallery management practicum course at Columbia College Chicago, seeks proposals from artists to lead participatory projects and/or workshops for ARTexchange.

ARTexchange projects and/or workshops will take place at the Columbia College Hokin Gallery, from February 12-15, 2020. The gallery is located a half block north of the Hilton Chicago conference hotel at 623 South Wabash. The work created will remain on exhibit through February 24, 2020. Proposals that include community engagement and meaningful interaction with CAA, Columbia College, and Chicago communities will be prioritized.

In collaboration with the Committee on Women in the Arts, CAA offers 50 percent of the 2020 conference’s content in celebration of the Centennial of Women’s Suffrage in the United States, while also acknowledging the discriminatory practices that limited voting rights for Indigenous women and women of color, even after the passage of the 19th amendment in 1920. The Services to Artists Committee encourages applicants to embrace the spirit of the 2020 conference by engaging issues of inclusivity and intersectional discourses in the arts.

Artists will have access to found objects or recycled materials donated and sourced that might include such things as office supplies, paper, fabric, paint, or drawing materials. A risograph with at least eight ink drums is at hand as a possible resource as well. Please consider that activities will take place in a public, open, non-studio environment and should not include toxic materials or processes.

Artists whose proposals are accepted must become CAA members. Complete information on CAA membership is available here.

The Hokin Project is a Gallery Management Practicum course of the Business and Entrepreneurship Department. Graduate and undergraduate students manage all aspects of the gallery to present multi-disciplinary work of the broader Columbia College Chicago community and beyond through programs, events, and exhibitions.

Please email any questions to hokingallery@gmail.com and artexchange2020@gmail.com. Include “CAA ARTexchange” in the subject line.

Deadline to submit (extended): November 8, 2019

- Contact information

- A short narrative bio (150 words or less)

- A short artist statement (150 words or less)

- Website URL (optional)

- A PDF (one file maximum 10 MB) of your proposal detailing your project, including materials requests, technical needs, and how you will engage the community (Chicago, CAA, and Columbia College Chicago) and/or consider inclusivity through the proposal. Please refer to the gallery plan, and if a particular space is preferable for the activity, make a note (please note that space will be shared amongst the accepted projects). If your project might take place over consecutive days, please note below in the Availability section. (up to 500 words)

- Work samples (5–10 images and/or links to 1–2 video/audio files)

- An image description list detailing the title, year completed, medium, and dimensions of each work. You may also include a short description describing how the work relates to the proposed project.

- Availability: your availability during different time slots during the conference and any other information related to scheduling.

International Review: Community-Led Engagement with Contemporary Craft, Design, and Architecture in Aotearoa

posted Oct 03, 2019

The following article was written in response to a call for submissions by CAA’s International Committee. It is by Linda Tyler, a New Zealand curator, writer, and academic who is Convenor of Museums and Cultural Heritage at the University of Auckland in New Zealand.

In the late 1990s, frustrated by the lack of a dedicated exhibition space for their work, a group of craft practitioners spearheaded an initiative to develop a dedicated craft gallery for Aotearoa (the Māori name for New Zealand). Following a successful bid for ongoing arts funding, Objectspace opened in 2004 in an old bank in the Auckland suburb of Ponsonby. It was the first of its kind, and after a dozen years of successful operation on this site, it underwent a transformation in 2017, moving into a purpose-designed building, and extending its scope to include architecture and design (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Objectspace’s new building opened in July 2017. Photo: Rebekah Robinson

Still the only public institution dedicated to craft and design in the country, in 2018 it extended its mandate even further. Seeking to increase engagement with Māori, Pacific, and Asian audiences and also to diversify the communities of makers which it supported, Objectspace launched the Maukuuku Project, a program of community-led activity, guided by the kaupapa (principles) of co-leadership, access, and advocacy.

Figure 2. Tuvalu master artist of maua talima (things created with the hands), Lakiloko Keakea is shown in this photograph framed by an example of her work. Titled Fafetu: Lakiloko Keakea, the exhibition was on view from September 30-November 11, 2018. Photo: Haru Sameshima

The first project in the new building began with a two-year engagement with members of the Tuvaluan community (a Pacific island people), culminating in a solo exhibition of craft by Lakiloko Keakea (Fig. 2). Challenging traditional notions of what types of crafts are understood to be part of the discourse, Maukuuku aims to change the system, recognizing the origin of many galleries and museums as institutions of colonization. Rather than inviting people into the gallery to work within its organization in a tokenistic way, the idea is to transform the organizational culture by turning over the gallery’s resources to a range of source communities from across Moana Oceania, Asia, and other migrant cultures who now call Aotearoa home.

Figure 3. Kim Hak, Alive, 2014, kettle and chicken. Included in the exhibition Alive: Kim Hak, June 2-July 21, 2019. Photo: Kim Hak

The second Maukuuku project, coordinated by Zoe Black, the new staff member charged with effecting the new direction at Objectspace, was Alive, by Kim Hak. Sponsored by the Rei Foundation, an Auckland-based Japanese funder dedicated to supporting research about peace and conflict, Alive brought artist Kim Hak from his home in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, to meet with twelve families who escaped the genocide in Cambodia in the late 1970s and resettled in Aotearoa as refugees. Wanting to document specific items that they brought with them—both precious and practical—Hak displayed the actual objects beside his photographs (Fig. 3). Often battered in transit, the focus on these material objects in the gallery setting prompted appreciation of the ordeal their owners had suffered and became a metaphor for the survival of their culture.

In a very short time, Objectspace has shown its ability to promote and advocate for art forms that have been marginalized, and communities that have never before been engaged by the gallery or museum sector in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Its ambition to introduce cultural change within the craft and design sector nationally, through forming co-leadership relationships with diverse communities of makers throughout Aotearoa is admirable. Already there has been increased engagement from Māori, Pacific, and Asian audiences, and it seems well underway toward fulfilling its mission to remove barriers to access.

The Maukuuku program will feature in a chapter written by Objectspace director Kim Paton for the forthcoming publication, Companion on Contemporary Craft, edited by Namita Gupter Wiggers, (Wiley Blackwell) to be published in 2020.

News from the Art and Academic Worlds

posted Oct 02, 2019

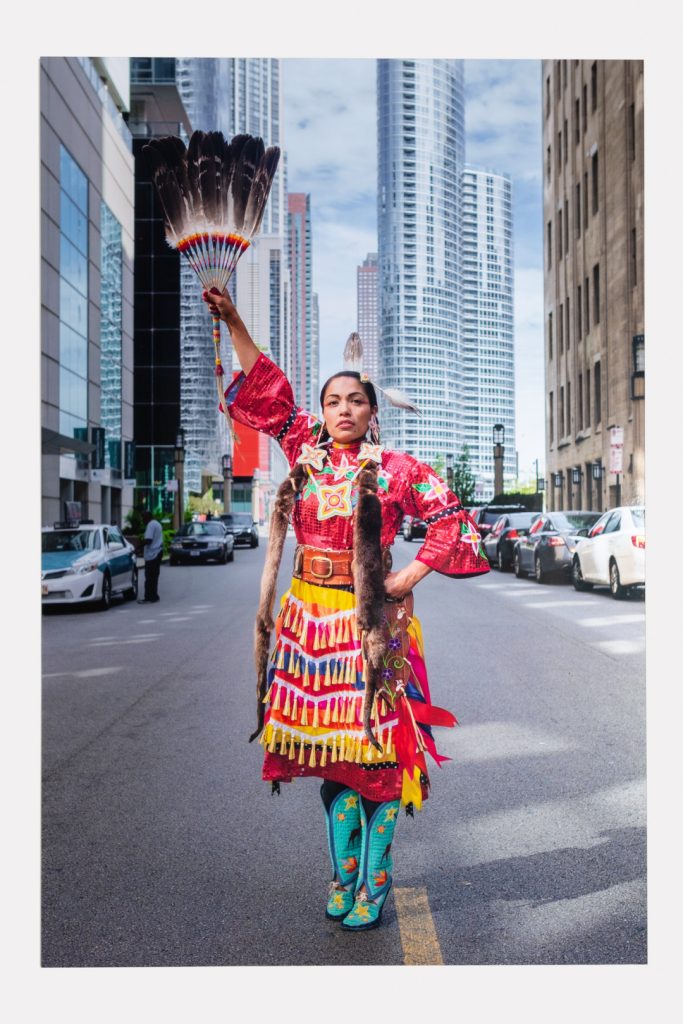

Adam Sings In The Timbers, Indigenizing Colonized Spaces with Starla Thompson, Potawatomi/Chumash, 2019, photo on Kodak Metallic Paper (installation photo by mel carter), via Hyperallergic

A Team of Curators Designs a System for Indigenous Artists to Thrive In

The term ‘decolonization’ has been used frequently to describe the exhibition yəhaw̓. But you won’t hear its curators call it a decolonial project. (Hyperallergic)

Why the Amsterdam Museum Will No Longer Use the Term ‘Dutch Golden Age’

The museum plans to remove all references to “Golden Age” in its galleries over the coming months. (Smithsonian Magazine)

How Ethical Can Museums Afford to Be? We Ask Five Major UK Art Institutions about Funding Challenges

Quite a headline. A look into the financials at five prominent UK museums. (The Art Newspaper)

Artist Adrian Piper Responds to artnet News‘s Special ‘Women’s Place in the Art World’ Report

“It is remarkable that your report neglects to examine what is arguably the most significant factor of all in perpetuating the invisibility of art made by women. It says nothing about artnet News’s own role in protecting the status quo.” (artnet News)

Want articles like these in your inbox? Sign up:

Announcing Notable Speakers for 2020 Annual Conference in Chicago

posted Oct 01, 2019

We’re delighted to announce the following guests will be presenting at the 108th CAA Annual Conference, taking place February 12-15, 2020, at the Hilton Chicago.

Keynote Speaker

Amanda Williams. Photo: David Kasnic Photography

The Keynote Speaker for the 108th CAA Annual Conference will be Amanda Williams. A visual artist who trained as an architect, Williams’s creative practice navigates the space between art and architecture, through works that employ color as a way to highlight the political complexities of race, place and value in cities. Williams has received critical acclaim including being named a USA Ford Fellow and a Joan Mitchell Foundation grantee. Her works have been exhibited widely and are included in the permanent collections of the Art Institute of Chicago and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. She lives and works on the South Side of Chicago.

CAA Convocation featuring Amanda Williams’s keynote will take place Wednesday, February 12, 2020, from 6-7:30 PM at the Hilton Chicago, Grand Ballroom. Free and open to the public.

Distinguished Scholar

The Distinguished Scholar for the 108th CAA Annual Conference will be Dr. Kellie Jones, professor in Art History and Archaeology and African American and African Diaspora Studies at Columbia University. Her research interests include African American and African Diaspora artists, Latinx and Latin American Artists, and issues in contemporary art and museum theory.

Dr. Kellie Jones. Photo: Rod McGaha

Dr. Jones, a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, has also received awards for her work from the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research, Harvard University and Creative Capital | Warhol Foundation. In 2016 she was named a MacArthur Foundation Fellow.

Dr. Jones’s writings have appeared in a multitude of exhibition catalogues and journals. She is the author of two books published by Duke University Press, EyeMinded: Living and Writing Contemporary Art (2011), and South of Pico: African American Artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s (2017), which received the Walter & Lillian Lowenfels Criticism Award from the American Book Award in 2018 and was named a Best Art Book of 2017 in The New York Times and a Best Book of 2017 in Artforum.

Dr. Jones has also worked as a curator for over three decades and has numerous major national and international exhibitions to her credit. Her exhibition “Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles, 1960-1980,” at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, was named one of the best exhibitions of 2011 and 2012 by Artforum, and best thematic show nationally by the International Association of Art Critics (AICA). She was co-curator of “Witness: Art and Civil Rights in the 1960s” (Brooklyn Museum), named one the best exhibitions of 2014 by Artforum. Read our interview with Kellie Jones.

The Distinguished Scholar Session will take place Thursday, February 13, 2020, from 4-5:30 PM at the Hilton Chicago, Grand Ballroom.

Distinguished Artist Interviews

The Distinguished Artist Interviews will feature artist Sheila Pepe interviewed by John Corso Esquivel, and artist Arnold J. Kemp interviewed by Huey Copeland.

Sheila Pepe. Photo: Rachel Stern

Sheila Pepe is a cross-disciplinary artist employing conceptualism, surrealism, and craft to address feminist and class issues. Hot Mess Formalism, Pepe’s most recent solo exhibition organized by the Phoenix Art Museum, traveled to the Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, New York; Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Omaha, Nebraska; and the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, Lincoln, Massachusetts between 2017 and 2019. A catalogue for the exhibition featured essays by by Julia Bryan-Wilson, Elizabeth Dunbar, Lia Gangitano, and curator Gilbert Vicario.

Other texts, all published in 2019, feature Pepe’s work: Vitamin T: Threads, and Textiles in Contemporary Art, the revised Art and Queer Culture by Catherine Lord and Richard Meyer, both published by Phaidon, and Feminist Subjectivities in Fiber Art and Craft: Shadows of Affect by John Corso Esquivel.

Venues for Pepe’s many other solo exhibitions include the Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Massachusetts, and the Weatherspoon Art Museum, Greensboro, North Carolina. Her work has been included in important group exhibitions, most recently Fiber: Sculpture 1960- Present, curated by Janelle Porter, organized by the ICA Boston; Queer Abstraction, curated by Jared Ladesema, organized by the Des Moines Art Center in Iowa and Even Thread Has Speech, curated by Shannon Stratton for the John Michael Kohler Art Center, Wisconsin.

John Corso Esquivel is the Doris and Paul Travis Associate Professor of Art History at Oakland University.

Arnold J. Kemp. Photo: Todd Rosenberg for the School of the Art Institute of Chicago

Arnold J. Kemp is an interdisciplinary artist living in Chicago. The recurrent theme in his drawings, photographs, sculptures and writing is the permeability of the border between self and the materials of one’s reality. Kemp’s works are in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Studio Museum in Harlem, The Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, The Portland Art Museum, The Schneider Museum of Art, and the Tacoma Art Museum. He has received awards from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, the Joan Mitchell Foundation, The Pollock-Krasner Foundation, and Portland Institute for Contemporary Art. His work has been exhibited recently in Chicago, Mexico City, New York, San Francisco and Portland. His work was also shown in Tag: Proposals On Queer Play and the Ways Forward at the ICA Philadelphia. Kemp was a founding curator at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts from 1993-2003 and is currently the Dean of Graduate Studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Read our interview with Arnold J. Kemp.

Huey Copeland is Arthur Andersen Teaching and Research Professor, Interim Director of the Black Arts Initiative (2019-2020), Associate Professor of Art History, and affiliated faculty in the Critical Theory Cluster, the Department of African American Studies, the Department of Art Theory & Practice, the Department of Performance Studies, and the Gender and Sexuality Studies Program at Northwestern University.

The Distinguished Artist Interviews will take place Friday, February 14, 2019, from 4-6:30 PM at the Hilton Chicago, Grand Ballroom. Free and open to the public.

Registration Now Open for the 2020 CAA Annual Conference

posted Oct 01, 2019

2020 CAA ANNUAL CONFERENCE

Hilton Chicago

FEBRUARY 12-15, 2020

Four days for everyone in the arts with over 300 sessions and panels, dozens of receptions and parties, professional development workshops, lightning talks, and exhibitors. #CAA2020

For the first time since 2014, the CAA Annual Conference returns to Chicago in February. We welcome all those in the visual arts to attend over 300 sessions and professional development workshops, as well as dozens of receptions, parties, and special tours at local museums and cultural institutions. The Book and Trade Fair, with over one hundred booths showcasing the latest products, programs, and books, will be on the lower level of the Hilton Chicago. Our partners offering free or discounted admission and special tours this year include Art Institute of Chicago, the Field Museum, the Design Museum of Chicago, and many others.

The 108th CAA Annual Conference content will address the full breadth of the field of visual arts and design and will examine a range of cultures, histories, and scholarship. We anticipate more than 5,000 professionals in the arts to attend the conference in Chicago. In collaboration with the Committee on Women in the Arts, we offer 50 percent of the conference’s content in celebration of the Centennial of Women’s Suffrage in the United States, while also acknowledging the discriminatory practices that limited voting rights for Indigenous women and women of color, even after the passage of the 19th amendment in 1920.

We are excited to announce that several renowned artists, designers, and scholars will be speaking at the conference. On Wednesday, February 12, Chicago-based visual artist Amanda Williams will be delivering the keynote address at Convocation. On Friday, February 14, our Artist Interviews will feature Sheila Pepe and Arnold J. Kemp, and this year’s Distinguished Scholar Session, held on February 13, will honor Kellie Jones.

Learn More about our Notable Speakers

Once again, CAA will offer travel grants and scholarships to individuals looking to attend the Annual Conference. With the generous support of Blick Art Materials and Routledge, Taylor & Francis, CAA will provide eight student member registrants with $250 each to attend the conference.

We look forward to seeing you in Chicago!

Please contact Member Services at membership@collegeart.org or at 212-691-1051, ext. 1 with any questions.

David Guinn and Joe Boruchow

posted Sep 30, 2019

The weekly CAA Conversations Podcast continues the vibrant discussions initiated at our Annual Conference. Listen in each week as educators explore arts and pedagogy, tackling everything from the day-to-day grind to the big, universal questions of the field.

CAA podcasts are on iTunes. Click here to subscribe.

This week, David Guinn and Joe Boruchow discuss how politics and family impact the artist.

David Guinn is an artist based in Philadelphia, working primarily in public space. A graduate of Columbia University in New York City, he was originally trained as an architect.

Joe Boruchow is a Philadelphia-based muralist and paper cutout artist whose site-specific work is designed to fit into architectural niches and public spaces.

New in caa.reviews

posted Sep 27, 2019

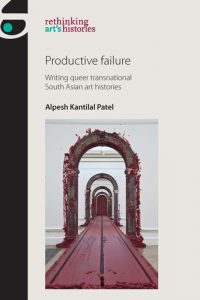

Rattanamol Singh Johal considers the book Productive Failure: Writing Queer Transnational South Asian Art Histories by Alpesh Kantilal Patel. Read the full review at caa.reviews.

Ian Bourland discusses Stick to the Skin: African American and Black British Art, 1965–2015 by Celeste-Marie Bernier. Read the full review at caa.reviews.

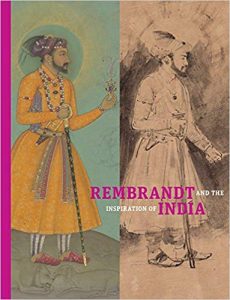

Sugata Ray reviews Rembrandt and the Inspiration of India, edited and curated by Stephanie Schrader. Read the full review at caa.reviews.