CAA News Today

Announcing the 2021 Awards for Distinction Recipients

posted by Allison Walters — February 10, 2021

Honorees this year include Samella Lewis, Deborah Willis, Kenneth Frampton, and many other scholars, artists, and teachers, including special commendation for service to art historical scholarship to Gillian Malpass.

CAA Annual Conference, February 10-13, 2021

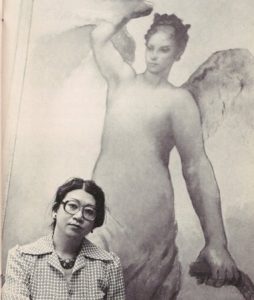

We are pleased to announce the recipients and finalists of the 2021 CAA Awards for Distinction. Among the winners this year is Samella Lewis, recipient of the 2021 Distinguished Artist Award for Lifetime Achievement. She was the first African American to earn a PhD in art history at Ohio State University. Mentored by Elizabeth Catlett and Charles White, Lewis embodied the visual culture of the civil rights movement through her prints. In addition to her studio practice, Lewis advocated African American art by writing for and creating exhibition venues. Her book, African American Art and Artists, originally published in 1978, was updated in subsequent editions and remains an important examination of more than two centuries of Black art and artists in the United States. For decades Lewis was a committed educator and scholar. In addition to her Fulbright, Lewis has been honored with a Charles White Lifetime Award (1993), with a UNICEF Award for the Visual Arts (1995), by being named a Getty Distinguished Scholar (1997), and by being interviewed by the HistoryMakers Archives (2003).

Deb Willis

and

Kenneth Frampton Photo credit: Alex Fradkin

Deborah Willis and Kenneth Frampton are the recipients of the 2021 Distinguished Lifetime Achievement Award for Writing on Art.

Deborah Willis has opened the field of African American photography. When the invention of photography coincided with the promise of abolition, a new arc of aspiration was combined. Its new pictures, thought to be the work of light itself, began to transmit images so that, as Frederick Douglass said, “Men of all conditions may see themselves as others see them.” From the first, photographs and photographic studios proliferated inside the Black community. It is the true extent of this practice that has been revealed by the lifework of Deborah Willis. In effect she has acted as its archaeologist, sifting through the layers from the time of Louis Daguerre to the surface of our present, retrieving the images and researching their histories.

Kenneth Frampton, trained as an architect, is a prolific architectural historian and critic who has managed to face the behemoth of globalized capital with an enduring version of humane modernity. Frampton has been writing about architecture for over half a century. A model of the architect-scholar, Frampton not only opens new cosmopolitan perspectives on the work of widely influential architects from Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn to Zaha Hadid and Álvaro Siza Vieira with his scholarship but also gives due attention to transitional spaces and movements.

Gillian Malpass

Gillian Malpass is the recipient of a CAA Commendation for Service to Art Historical Scholarship. As publisher of art and architectural history at Yale University Press, London, Gillian Malpass assembled a matchless list of titles over three decades that set the press apart from all others. She fostered projects that were gorgeously designed, accessibly written, and beautifully illustrated, including numerous now-classic books by both emerging and senior scholars. She worked on monographs, exhibition catalogs, reference, and biography, from books examining previously unexplored fields to bestsellers. Authors of many of the most important books published in art history over the past thirty years attest in their prefaces to the ways in which Malpass’s encouragement, expertise, and eye shaped their work.

The Awards for Distinction will be presented during Convocation at the CAA Annual Conference on Wednesday, February 10 at 6:00 PM. This event is free and open to the public. A free and open registration is required.

The full list of 2021 CAA Awards for Distinction Recipients:

Sampada Aranke

Sampada Aranke, “Blackouts and Other Visual Escapes,” Art Journal, vol. 79, no. 4 (Winter 2020): 62–75

Katherine A. Bussard

Kristen Gresh Photo credit: Oswaldo Ruiz

Katherine A. Bussard and Kristen Gresh, eds., “Life” Magazine and the Power of Photography, Princeton University Art Museum, 2020

and

Louis Marchesano

Louis Marchesano, ed., Käthe Kollwitz: Prints, Process, Politics, Getty Research Institute, 2020

Julieta Gonzalez

Tomás Toledo

Adriano Pedrosa

José Esparza Chong Cuy

Alfred H. Barr Jr. Award for Smaller Museums, Libraries, Collections, and Exhibitions

Adriano Pedrosa, José Esparza Chong Cuy, Julieta González, and Tomás Toledo, Lina Bo Bardi: Habitat, Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand (MASP) / DelMonico Books, 2020

Nicole R. Fleetwood Photo credit: Bayeté Ross Smith

Nicole R. Fleetwood, Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration, Harvard University Press, 2020

Charles L. Davis, II

Charles Rufus Morey Book Award

Charles L. Davis, II, Building Character: The Racial Politics of Modern Architectural Style, University of Pittsburgh Press, 2019

and

Nicole R. Fleetwood Photo credit: Bayeté Ross Smith

Nicole R. Fleetwood, Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration, Harvard University Press, 2020

Adam Jasienski

Adam Jasienski, “Converting Portraits: Repainting as Art Making in the Early Modern Hispanic World,” The Art Bulletin, vol. 102, no. 1 (March 2020): 7–30

Jessie Park

Honorable Mention:

Jessie Park, “Made by Migrants: Southeast Asian Ivories for Local and Global Markets, ca. 1590–1640,” The Art Bulletin, vol. 102, no. 4 (December 2020): 66–89

Maren Hassinger Photo credit: Ava Hassinger

Artist Award for a Distinguished Body of Work

Maren Hassinger

Nancy Odegaard

CAA/AIC Award for Distinction in Scholarship and Conservation

Nancy Odegaard

Samella Lewis

Distinguished Artist Award for Lifetime Achievement

Samella Lewis

Deb Willis

and

Kenneth Frampton Photo credit: Alex Fradkin

Distinguished Lifetime Achievement Award for Writing on Art

Deborah Willis and Kenneth Frampton

Simone Leigh Photo credit: Kyle Kodel

Distinguished Feminist Award—Artist

Simone Leigh

Katy Deepwell

Distinguished Feminist Award—Scholar

Katy Deepwell

Dona Nelson

Distinguished Teaching of Art Award

Dona Nelson

Kaori Kitao

Distinguished Teaching of Art History Award

Kaori Kitao

Margo Machida

Margo Machida

Gillian Malpass

CAA Commendation for Service to Art Historical Scholarship

Gillian Malpass

Learn about the juries that select the recipients of the CAA Awards for Distinction.

CWA Picks: December 2020

posted by Allison Walters — December 15, 2020

December CWA Picks

December Picks from the Committee on Women in the Arts celebrate a selection of events, exhibitions and calls for work and participation featuring feminist and womxn artists and addressing issues concerning social justice and ethics in intersectional and transnational perspectives.

Food Justice In Appalachia: Call For Content; An exhibit by WVU Libraries in partnership with the WVU Food Justice Lab and the WVU Center for Resilient Communities.

https://exhibits.lib.wvu.edu/gallery_foodjustice

The call (deadline on February 1st, 2021; exhibition launch in August 2021) invites submissions exploring concepts of food justice, food sovereignty and community food security. Selected works will be included in an exhibition, which focuses on ways in which the food system shapes landscapes, defines economic systems and informs cultural practices.

Curators Conversation: Curating the Digital — a Webinar hosted by Art Curator Grid and SALOON London on December 17th, 2020

https://www.eventbrite.pt/e/curators-conversation-curating-the-digital-tickets-129483736341

Curators Julia Greenway and Noelia Portela will be in conversation with SALOON London co-founder Mara-Johanna Kolmel to explore the online spheres and the digital realm in curatorial practices. SALOON London is a professional network for women in the arts with the objective of creating an open forum to exchange ideas, experiences and initiate collaborations.

Online exhibition accompanying On Transversality in Practice and Researchconference 9-11 December 2020, organised by PhD students from across the UK

https://ontransversality.wordpress.com/exhibition/

This exhibition presents the works of Maria Teresa Gavazzi, Emily Beaney, Stav B and Caio Amado Soares, and Niya B. who reflect on the issues addressed by the conference themes: interdisciplinarity, intersectionality and transnationalism in research praxis, from anti-racist, decolonial, feminist, and queer methodological perspectives.

Feminist Art Coalition (FAC)

https://feministartcoalition.org/

FAC, a platform for art projects informed by feminisms, encourages collaborations between arts institutions with the aim of promoting and advocating for social justice and structural change. A series of collaboratively conceived events and exhibitions planned for 2020 have been postponed to 2021 because of COVID-19 closures.

Our inheritance was left to us by no testament prelude exhibition to OnHannah Arendt: Eight Proposals for Exhibition; Richard Saulton Gallery, London

Richard Saulton Gallery launches its programme ‘On Hannah Arendt’ in January 2021 addressing the political philosopher’s 1968 publication Between Past and Future, in which Arendt questions the lost freedoms in the period post World War II and the threads of broken traditions. The group exhibition Our inheritance was left to us by no testament, a prelude to the launch, features the work of seven women artists from Eastern Europe, Alina Szapocznikow, Barbara Levittoux-Świderska, Renate Bertlmann, Běla Kolářová, Jagoda Buić, Jolanta Owidzka and Erna Rosenstein, that speak to possibilities in art without tradition.

Vote for CAA’s 2021 Board of Directors

posted by Allison Walters — December 03, 2020

As a CAA member, voting is one of the best ways to shape the future of your professional organization. Thank you for taking the time to vote! Scroll down to meet this year’s candidates and submit your online voting form.

2021 CAA Board of Directors candidates, from left to right, top to bottom: Roland Betancourt, Patricia Childers, Alberto De Salvatierra, Lara Evans, Charles Kanwischer, Wanda Raimundi-Ortiz, Kelvin Parnell, and Kelly Walters.

2021 CAA BOARD OF DIRECTORS ELECTION

The CAA Board of Directors is comprised of professionals in the visual arts who are elected annually by the membership to serve four-year terms (or, in the case of the Emerging Professional Board members, two-year terms). The Board is charged with CAA’s long-term financial stability and strategic direction; it is also the Association’s governing body. The board sets policy regarding all aspects of CAA’s activities, including publishing, the Annual Conference, awards and fellowships, advocacy, and committee procedures. For more information, please read the CAA By-laws on Nominations, Elections, and Appointments.

MEET THE CANDIDATES

The 2020–21 Nominating Committee has selected the following candidates for election to the CAA Board of Directors. Click the names of the candidates below to read their statements and resumes before casting your vote.

BOARD OF DIRECTOR CANDIDATES (FOUR-YEAR TERM, 2021-2025)

Roland Betancourt, Professor of Art History, University of California Irvine, Irvine, CA

Alberto De Salvatierra, Assistant Professor of Urbanism and Data in Architecture + Director of the Center for Civilization, University of Calgary School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape (SAPL), Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Alberto De Salvatierra, Assistant Professor of Urbanism and Data in Architecture + Director of the Center for Civilization, University of Calgary School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape (SAPL), Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Lara Evans, Interim Director, Research Center for Contemporary Native Arts, Institute of American Indian Arts, Santa Fe, NM

Charles Kanwischer, Director, School of Art, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, OH

Wanda Raimundi-Ortiz, Associate Professor, Studio Art, University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL

Wanda Raimundi-Ortiz, Associate Professor, Studio Art, University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL

Kelly Walters, Associate Director, BFA Communication Design Program, Parsons School of Design, The New School, New York, NY

Kelly Walters, Associate Director, BFA Communication Design Program, Parsons School of Design, The New School, New York, NY

Emerging Professionals BOARD OF DIRECTOR CANDIDATES (TWO-YEAR TERM, 2021-2023)

Patricia Childers, Adjunct Faculty, New York City College of Technology, City University of New York (CUNY), Communication Design Department, New York, NY

Kelvin Parnell, Ph.D. Candidate, Art and Architectural History, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA

CAA members must cast their votes for board members online using the link below; no paper ballots will be mailed. The deadline for voting is 6:00 p.m. EST on February 11, 2021.

The elected individuals will be announced at CAA’s Annual Business Meeting to be held at 2:00 p.m. on Friday, February 12, 2021.

Questions? Contact Vanessa Jalet, executive liaison, at (212) 392-4434 or vjalet@collegeart.org

CAA Table Talk, November 18, 2020

posted by Allison Walters — November 24, 2020

We’re delighted to introduce CAA members to a new series of conversations between Meme Omogbai, our executive director and CEO, and N. Elizabeth Schlatter, the president of the CAA Board of Directors. Amidst so much change in our lives, workplaces, and world, CAA leadership sat down for an informal chat on how CAA is reshaping its efforts to provide access and resources where members need it most. Meme and Elizabeth will speak on the economic implications of COVID-19, the urgent importance of members’ scholarship, and the changing terrain of this cultural moment.

This discussion is centered around the Annual Conference and CAA’s pivot towards a digital-first platform, inspired by many of the questions submitted by members.

We would love to hear your questions for future CAA Table Talk conversations. Please send them in advance to: caanews@collegeart.org

SPEAKER BIOGRAPHIES

Meme Omogbai is Executive Director and CEO of College Art Association (CAA). Before joining CAA, Omogbai served as a member and past Board Chair of the New Jersey Historic Trust, one of four landmark entities dedicated to preservation of the state’s historic and cultural heritage and Montclair State University’s Advisory Board. Named one of 25 Influential Black Women in Business by The Network Journal, Meme has over 25 years of experience in corporate, government, higher education, and museum sectors. As the first American of African descent to chair the American Alliance of Museums, Omogbai led an initiative to rebrand the AAM as a global, inclusive alliance. While COO and Trustee, she spearheaded a major transformation in operating performance at the Newark Museum. During her time as Deputy Assistant Chancellor of New Jersey’s Department of Higher Education, Omogbai received Legislative acknowledgement and was recognized with the New Jersey Meritorious Service Award for her work on college affordability initiatives for families. Omogbai received her MBA from Rutgers University and holds a CPA. She did post-graduate work at Harvard University’s Executive Management Program and has earned the designation of Chartered Global Management Accountant. She studied global museum executive leadership at the J. Paul Getty Trust Museum Leadership Institute, where she also served on the faculty.

Elizabeth Schlatter is the President of the CAA Board of Directors and Deputy Director and Curator of Exhibitions at the University of Richmond Museums, Virginia. A museum administrator, curator, and writer, she focuses on modern and contemporary art and on topics related to curating and issues specific to university museums. At UR, she has curated more than 20 exhibitions, including recent group exhibitions of contemporary art such as “Crooked Data: (Mis)Information in Contemporary Art,” “Anti-Grand: Contemporary Perspectives on Landscape,” and “Art=Text=Art: Works by Contemporary Artists.” She also serves on and chairs various University and School of Arts & Sciences committees. Prior to the University of Richmond, she worked with exhibitions at the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service (SITES) in Washington, D.C, and in fundraising at the Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston. She is author ofMuseum Careers: A Practical Guide for Novices and Students (Left Coast Press, Inc.) and a contributor to A Life in Museums: Managing Your Museum Career (American Association of Museums). She has a BA in art history from Southwestern University in Texas, and an MA in art history from George Washington University.

Recording now available–CAA Table Talk: Education and the Arts in a Time of Crisis

posted by CAA — October 05, 2020

Wednesday, October 14, 2020

12:00-12:30 PM (ET)

Free and open to the public

CLICK HERE TO JOIN THE CONVERSATION

We’re delighted to introduce CAA members to a new series of conversations between Meme Omogbai, our executive director and CEO, and N. Elizabeth Schlatter, the president of the CAA Board of Directors. Amidst so much change in our lives, workplaces, and world, join CAA leadership for an informal chat on how CAA is reshaping its efforts to provide access and resources where members need it most. Meme and Elizabeth will speak on the economic implications of COVID-19, the urgent importance of members’ scholarship, and the changing terrain of this cultural moment.

For best results, we recommend using the most up-to-date version of Chrome as your web browser. The conversation will be recorded and shared afterwards.

We would love to hear your questions, too. Please send them in advance to: caanews@collegeart.org

SPEAKER BIOGRAPHIES

Meme Omogbai is Executive Director and CEO of College Art Association (CAA). Before joining CAA, Omogbai served as a member and past Board Chair of the New Jersey Historic Trust, one of four landmark entities dedicated to preservation of the state’s historic and cultural heritage and Montclair State University’s Advisory Board. Named one of 25 Influential Black Women in Business by The Network Journal, Meme has over 25 years of experience in corporate, government, higher education, and museum sectors. As the first American of African descent to chair the American Alliance of Museums, Omogbai led an initiative to rebrand the AAM as a global, inclusive alliance. While COO and Trustee, she spearheaded a major transformation in operating performance at the Newark Museum. During her time as Deputy Assistant Chancellor of New Jersey’s Department of Higher Education, Omogbai received Legislative acknowledgement and was recognized with the New Jersey Meritorious Service Award for her work on college affordability initiatives for families. Omogbai received her MBA from Rutgers University and holds a CPA. She did post-graduate work at Harvard University’s Executive Management Program and has earned the designation of Chartered Global Management Accountant. She studied global museum executive leadership at the J. Paul Getty Trust Museum Leadership Institute, where she also served on the faculty.

N. Elizabeth Schlatter is the President of the CAA Board of Directors and Deputy Director and Curator of Exhibitions at the University of Richmond Museums, Virginia. A museum administrator, curator, and writer, she focuses on modern and contemporary art and on topics related to curating and issues specific to university museums. At UR, she has curated more than 20 exhibitions, including recent group exhibitions of contemporary art such as “Crooked Data: (Mis)Information in Contemporary Art,” “Anti-Grand: Contemporary Perspectives on Landscape,” and “Art=Text=Art: Works by Contemporary Artists.” She also serves on and chairs various University and School of Arts & Sciences committees. Prior to the University of Richmond, she worked with exhibitions at the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service (SITES) in Washington, D.C, and in fundraising at the Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston. She is author of Museum Careers: A Practical Guide for Novices and Students (Left Coast Press, Inc.) and a contributor to A Life in Museums: Managing Your Museum Career (American Association of Museums). She has a BA in art history from Southwestern University in Texas, and an MA in art history from George Washington University.

Call for Participation: CAA 2021 Poster Session Highlighting Undergraduate Research in Art and Art History

posted by CAA — October 05, 2020

Cecilia Bugno presents her work as part of the inaugural Undergraduate Research Poster Presentations at the 2020 Annual Conference. Photo: Stacey Rupolo

We’re excited to announce the 2021 Call for Participation for a special virtual poster session dedicated to undergraduate research for the 2021 Annual Conference, February 10-13.

Organized by Alexa Sand, Chair of the Division of Arts and Humanities for the Council on Undergraduate Research, and Professor of Art History and Director of Undergraduate Research at Utah State University, this session is one of several events planned for CAA 2021 to provide more opportunities for undergraduate participation.

Submissions should be sent via this google form by November 23, 2020.

Selected presenters will be notified by December 7 and will need to join CAA at the student membership rate prior to participation in the conference. Participants will also be required to register for the conference.

Undergraduate research—whether part of a faculty-directed project, class-based, or an individual pursuit on the part of a student—is an ideal example of active and engaged learning. Students in art history identify questions, evaluate source material, test ideas and theories, and produce reports in some form, usually including a significant written component. In the studio art and design fields, research can take a different form, with creative practice being one way outcomes of a project can be delivered.

This poster session will be dedicated to presenting outstanding examples of undergraduate research. Submissions are invited from students conducting research such as object and/or medium studies, text-based analysis, experimental archaeology, thesis research, and/or creative inquiry. Students may choose to present findings from ongoing research or from recently completed projects.

We also encourage submissions from faculty and museum professionals who have experience with mentoring undergraduate research in Art History, Studio Art, Graphic Design, Visual Communication, and other creative fields. Faculty posters may address specific projects or case studies of student research projects, assessment of undergraduate research, characteristics of successful programs, or other approaches that addresses the challenges and benefits to students of undergraduate research.

This project proposal is part of CAA’s Undergraduate Outreach Initiative organized collaboratively by CAA’s Education Committee, Committee on Diversity Practices, Students and Emerging Professionals Committee, and the Division of Arts and Humanities, Council on Undergraduate Research.

Please contact Alexa Sand directly at alexa.sand@usu.edu with any questions.

Announcing the Appointment of Three New Editors for CAA Publications

posted by CAA — October 01, 2020

We’re pleased to announce the appointment of three new editors for CAA publications: editor designate Eddie Chambers, who will take up his post as Editor-in-Chief of Art Journal, July 2021 – June 2024; Julie Nelson Davis, current Editor-in-Chief of caa.reviews, July 2020 – June 2023; and editor designate Stephanie Porras, who will take up her post as Reviews Editor of The Art Bulletin, July 2021 – June 2024. Learn more about their work below.

EDITOR BIOGRAPHIES

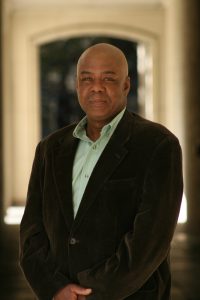

Eddie Chambers | Incoming Editor-in-Chief of Art Journal, July 2021 – June 2024

Eddie Chambers was born in Wolverhampton, England. He gained his PhD from Goldsmiths College, University of London in 1998, for his study of press and other responses to the work of a new generation of Black artists in Britain, active during the 1980s. He joined the Department of Art and Art History at the University of Texas at Austin in January 2010 where he is now a Professor. His books include Things Done Change: The Cultural Politics of Recent Black Artists in Britain (Rodopi Editions, Amsterdam and New York, 2012), Black Artists in British Art: A History Since the 1950s, (I. B. Tauris, London and New York, 2014, reissued 2015), and Roots & Culture: Cultural Politics in the Making of Black Britain, published 2017 (I. B. Tauris/Bloomsbury). He is the editor of the recently-published Routledge Companion to African American Art History. His forthcoming book is World is Africa: Writings on Diaspora Art (Bloomsbury, 2021).

Eddie Chambers was born in Wolverhampton, England. He gained his PhD from Goldsmiths College, University of London in 1998, for his study of press and other responses to the work of a new generation of Black artists in Britain, active during the 1980s. He joined the Department of Art and Art History at the University of Texas at Austin in January 2010 where he is now a Professor. His books include Things Done Change: The Cultural Politics of Recent Black Artists in Britain (Rodopi Editions, Amsterdam and New York, 2012), Black Artists in British Art: A History Since the 1950s, (I. B. Tauris, London and New York, 2014, reissued 2015), and Roots & Culture: Cultural Politics in the Making of Black Britain, published 2017 (I. B. Tauris/Bloomsbury). He is the editor of the recently-published Routledge Companion to African American Art History. His forthcoming book is World is Africa: Writings on Diaspora Art (Bloomsbury, 2021).

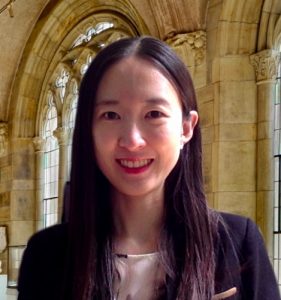

Julie Nelson Davis | Current Editor-in-Chief of caa.reviews, July 2020 – June 2023

Julie Nelson Davis is Professor of the History of Modern Asian Art at the University of Pennsylvania. Recognized as one of the world’s foremost authorities on Japanese prints and illustrated books, Davis teaches a wide range of courses on East Asian art and material culture in the greater global context. After receiving her BA from Reed College, Davis completed her MA and PhD from the University of Washington and studied at Gakushūin University in Tokyo. She is author of Utamaro and the Spectacle of Beauty (Reaktion Books, 2007 and 2021), Partners in Print: Artistic Collaboration and the Ukiyo-e Market (University of Hawai’i Press, 2015), and Picturing the Floating World: Ukiyo-e in Context (in press). Davis was recently a guest curator for the Freer and Sackler Galleries for an exhibition on Utamaro (2017) and is preparing an exhibition of Japanese illustrated books at the University of Pennsylvania. She is currently working on a new project on issues of imitation, homage, and fakery in early modern Japanese art and their legacies into the present. In addition to her tenure as caa.reviews Editor-in-Chief from 2020 to 2023, Davis served as the field editor for Japanese art from 2001 to 2010 and a board member from 2007 to 2011.

Stephanie Porras | Incoming Reviews Editor of The Art Bulletin, July 2021 – June 2024

Stephanie Porras is Associate professor of Art History in the Newcomb Art Department at Tulane University, specializing in early modern art made in Northern Europe and across the Spanish world. Author of Pieter Bruegel’s Historical Imagination (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2016) and Northern Renaissance Art: Courts, Commerce, Devotion (Laurence King, 2018), Porras has also published widely on topics ranging from Albrecht Dürer’s drawings to Hispano-Philippine ivories. Her current book project, The First Viral Images considers the mobility of early modern artworks and their role in processes of globalization, and has been supported by fellowships at the New York Public Library, the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, and the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts at the National Gallery of Art.

Stephanie Porras is Associate professor of Art History in the Newcomb Art Department at Tulane University, specializing in early modern art made in Northern Europe and across the Spanish world. Author of Pieter Bruegel’s Historical Imagination (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2016) and Northern Renaissance Art: Courts, Commerce, Devotion (Laurence King, 2018), Porras has also published widely on topics ranging from Albrecht Dürer’s drawings to Hispano-Philippine ivories. Her current book project, The First Viral Images considers the mobility of early modern artworks and their role in processes of globalization, and has been supported by fellowships at the New York Public Library, the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, and the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts at the National Gallery of Art.

International News: The Treasures of the Punjab Archives, Lahore, Pakistan

posted by CAA — September 28, 2020

The following article was written in response to a call for submissions by CAA’s International Committee. It is by Kanwal Khalid, Director of the Punjab Archives, Lahore, Pakistan, and an alumna of the CAA-Getty International Program.

Figure 1. The Punjab Archives, housed in the Tomb of Anarkali, a building from the reign of Mughal Emperor Jahangir (1605-1627). (All photographs in this article provided by the author)

Having spent my career as a university professor, I recently was appointed the director of the Punjab Archives in Lahore. This rich collection is one of the best in South Asia and I am pleased to share a description of the institution, which also includes a library and museum, with readers of CAA News, who will soon be able to access many of the collection’s materials online.

The history of every nation is important and documents that reveal a nation’s history become increasingly precious over time. The majority of these documents are held in archives—collections that are both accumulations of historical data and repositories of record. Pakistan contains many rich archival collections: The National Archives of Pakistan and the National Documentation Centre, both located in Islamabad; the Sindh Archives in Karachi; and the Baluchistan Archives in Quetta. But the oldest of them all is the Punjab Archives in Lahore, located inside the Tomb of Anarkali.

The Punjab Archives is significant both for the immense value of its holdings and for the historical importance of its building (Fig.1), which was built during the reign of Mughal Emperor Jahangir (1605-1627). It was originally a tomb attributed to a woman named Anarkali, traditionally thought to be a concubine of Jahangir’s. According to the date written on the cenotaph, the monument was completed in 1615. The building has witnessed many ups and downs in its four-hundred-year history. After the annexation of Punjab by the British in 1849, the building was used as storage for documents pouring in from all parts of South Asia that were under the control of the British Raj. Two years later it became a church used for Sunday services, but in 1891 it was declared a record office.

Figure 2. Inside view of the Archives.

Punjab Archives Collection

The Punjab Archives (Figs. 2, 3a-b) holds one of the largest repositories of documents in South Asia and it is responsible for the safekeeping of official documents and records of the Pakistan government. It houses census reports, civil and military gazettes, official files, historical documents, manuscripts, handouts, brochures, pamphlets, maps, notifications, memoranda, lithographs, research papers, journals, magazines, newspapers and periodicals. Many of these cannot be found anywhere else in the world. The archive also includes a fine collection of miniature paintings and seals.

The records in the Punjab Archives date back to the seventeenth century and cover the Mughal, precolonial, colonial and postcolonial eras in South Asia. Primarily the collection consists of:

- Persian Record of Mughal Period, 1629-1858

- Persian Record of Sikh Period, 1799-1849

- Akhbar Darbar-e-Lahore (Daily Court Proceedings of Sikh Rulers), 1835-1849

- Persian Record of British Period, 1809-1890

- Old Persian Newspapers, 1840-1845

- Colonial Agencies Record, 1804-1849

- Record of Princely States in Punjab, 1849-1947

- Record After the Annexation, 1849 to 1947

- Record After Independence, 1947

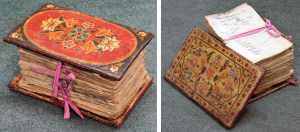

Figure 3a, b. Beautifully illuminated wooden boards used as file holders, first half of 19th century.

The Archival Library

Sir Edward Meclagan served as chancellor of University of the Punjab (1919-1924) and Governor of Punjab (1923). He was a historian whose passion for knowledge is evidenced by his donation of rare and out of print books to the Archives. This initiative led to the establishment of a small but important library that still exists today.

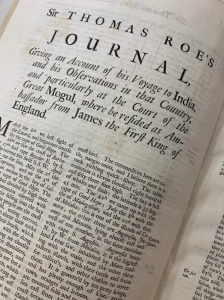

Figure 4. The oldest book in the Archives Library, Sir Thomas Roe’s Journal, 1616.

The collection consists of biographies, reports and travelogues. Currently the library holds more than 70,000 highly valuable reference books. The oldest book is a memoir, Journal of Sir Thomas Roe, which dates to 1616 and recounts the author’s journey to different parts of India (Fig. 4).

Figure 5. The central hall of the tomb, housing the Archives Museum.

Archives Museum

Another person who played an important role for the Archives was Lord Malcolm Hailey. He went one step beyond his predecessor and established a small museum in 1924 in the central hall of the tomb (Fig. 5). This collection, still maintained today, contains portraits of important Lahore personalities (Fig. 6), along with paintings, prints, maps and lithographs. Mughal Farmans (proclamations), important official letters, old stamps, medals, weapons, and miniatures are also on display (Fig. 7).

Digitization

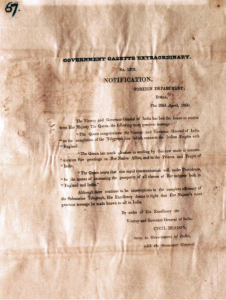

Figure 7. A message from the Queen of England to the viceroy on the completion of the telegraph line to India, 1860.

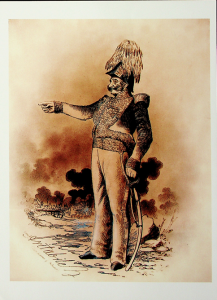

Figure 6. A general of Ranjit Singh’s army, General Avitabile, early 19th century.

For the past several years, the Punjab Archives has been in the process of digitizing its collection to improve accessibility to scholars. Approximately 500,000 pages of historic documents are currently being scanned and catalogued, precluding the need to move the fragile original documents, thus minimizing their wear and tear. A web portal will make these digitized documents accessible under the authorization of the Punjab Archives. This project is a first step towards a long-term strategy of modernizing the Punjab Archives and Libraries. To date, more then 120,000 pages have been digitized. Although the project was scheduled to be completed by June 2021, the Covid-19 pandemic has brought all activities to a standstill. Once completed, the archives online services will be a primary resource for scholars throughout the world. In the meantime we are providing information to any researcher who contacts the Archives Department by email at archivesdirectorate@gmail.com.

Explore RAAMP’s Resources on the CAA Website

posted by CAA — July 30, 2020

RAAMP (Resources for Academic Art Museum Professionals) has a new home! Moving forward, you can find all the resources you know and love here on our website at: collegeart.org/raamp

A project of CAA with support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, RAAMP aims to strengthen the educational mission of academic museums and their parent organizations by providing a publicly accessible repository of resources, online forums, and relevant news and information. RAAMP’s coffee gatherings and video practica cover a wide variety of topics including advocacy, engagement, curricula building, cross-disciplinary collaboration, technology, development, and censorship.

To receive updates and invitations to upcoming RAAMP programming, sign up for the RAAMP mailing list.

For any questions regarding the RAAMP program, please contact Cali Buckley, grants and special programs manager, at: cbuckley@collegeart.org

An Update on the 2021 Annual Conference

posted by CAA — July 16, 2020

Dear CAA Members,

As you will hear Meme Omogbai, CAA executive director, say time and time again, “Mission first. People always.” So we start this letter with the wish that you are safe, healthy, and finding some time for self-care this summer.

We are writing to share where we are in planning the 109th CAA Annual Conference. We had hoped to celebrate the vast scholarship and practice of CAA members at a fully in-person conference in New York this February 10–13, 2021. The COVID-19 pandemic and the uncertainty of the months ahead—as well as increasing economic pressures on institutions and individuals, leading to diminished funds for professional development and travel—have caused us to rethink our plans.

We are now moving to a conference format that will include session content online. There are many factors in determining the costs and benefits to going online; these are currently being worked on by CAA staff and will continue to be addressed as we move forward. But making this decision now allows staff and the Annual Conference Committee time to plan for an iteration of the conference that will ensure the core benefits of the event are maintained: opportunities to share new research, listen to esteemed artists, designers, and scholars, and connect with peers. We are also looking at ways to present the in-person activities, dependent upon the state of the pandemic in early 2021. Thank you for your patience and flexibility over the next couple of months as the planning continues. We are creating a list to address your frequently asked questions; please email questions to programs@collegeart.org or to us personally.

SEE FAQS FOR 2021 ANNUAL CONFERENCE

Our decision was informed by a robust response (almost 1,200 replies!) to a survey sent to members in May regarding their ideas about CAA hosting an online conference. Exceptionally useful feedback was provided in terms of what types of activities would be appealing to attend online, the value of in-person gatherings, and what price points seem reasonable. We are building on what you shared with us.

The Annual Conference Committee is currently reviewing the 800-plus proposal submissions and is on schedule to select those that will be included in the conference program. Our committees and staff are working hard to create a diverse and inclusive program and one that is broadly accessible.

While this time is filled with uncharted unknowns and anxieties, this is also an opportunity for us to build the organization that we want CAA to be. If you have the ability to give, we ask for your generosity. If you are able to give financially, wonderful—we need that help. Donations are not the only way to participate in our organization, however. We want your energy and your ideas. If you have connections and resources to share, we welcome them. If you know people who could benefit from our community, please spread the word. We are an organization of members. Join us.

CAA is an incredible coalition of individuals and institutions. If we have learned anything from the pandemic, it is that virtual platforms can allow us to communicate broadly and across borders. Difficult conversations can take place and together we can move forward and create an organization that advocates, shares, and brings others along with us.

Sincerely yours,

N. Elizabeth Schlatter

President, CAA

Deputy Director, University of Richmond Museums, Virginia

Meme Omogbai

Executive Director and CEO