CAA News Today

News from the Art and Academic Worlds

posted by CAA — Jul 01, 2020

The Tsai Performance Center on the campus of Boston University, Boston. Photo: Steven Senne/AP, via WGBH

|

Want articles like these in your inbox? Sign up for our weekly newsletter:

RAAMP Coffee Gathering: Gender Equity in the Museum (and Arts) Workplace

posted by CAA — Jun 30, 2020

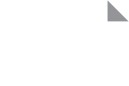

Coffee Gathering: Gender Equity in the Museum (and Arts) Workplace

On Thursday, July 2 at 2:00 PM (EST) we will speak with Anne Ackerson and Joan Baldwin on gender equity in museums and workplaces.

To RSVP to this Coffee Gathering, please fill out this form.

A former museum director, Joan H. Baldwin is the Curator of Special Collections at The Hotchkiss School. She is the principal writer for the Leadership Matters blog which had 55,000 views in 2018. Her work has also appeared in The Museum Blog Book, “History News,” and “Museum” Magazine, Museopunks, and “The Guardian.” She is a co-founder of the Gender Equity in Museums Movement, and teaches in the Johns Hopkins University museum studies program. With Anne Ackerson, she is the co-author of Leadership Matters (2013) and Women in the Museum: Lessons from the Field (2017). She and Ackerson published a revision of Leadership Matters: Leading Museums in an Age of Discord in August 2019.

Anne W. Ackerson is a former history museum director, director of the Museum Association of New York, and director of the national Council of State Archivists. She is currently an independent consultant to cultural and educational nonprofits, specializing in leadership, governance, and management issues. With Joan H. Baldwin, she is the co-author of Leadership Matters, a book examining history museum leadership for the 21st century, and Women in the Museum: Lessons from the Workplace. She is a co-founder of the Gender Equity in Museums Movement (GEMM), which is focusing its recent efforts on education, advocacy, and policy development around pay equity, salary transparency, and sexual harassment in the museum workplace. In 2018, she and Baldwin spearheaded research, revealing that 62% of the museum workforce are affected by some form of gender discrimination. In addition to research and writing about gender inequity, she and Baldwin have presented their findings to the Texas and Pennsylvania Associations of Museums as conference keynoters and via their blog, Leadership Matters.

RAAMP Coffee Gatherings are monthly virtual chats aimed at giving participants an opportunity to informally discuss a topic that relates to their work as academic art museum professionals. Learn more here.

Submit to RAAMP

RAAMP (Resources for Academic Art Museum Professionals) aims to strengthen the educational mission of academic art museums by providing a publicly accessible repository of resources, online forums, and relevant news and information. Visit RAAMP to discover the newest resources and contribute.

RAAMP is a project of CAA with support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the Samuel H. Kress Foundation.

Serve on a CAA Jury and Provide Support to the Field

posted by CAA — Jun 24, 2020

Former CAA Interim Director David Raizman and Denise Murrell, who received the Alfred H. Barr Jr. Award for Smaller Museums, Libraries, Collections, and Exhibitions for her catalog Posing Modernity: The Black Model From Manet and Matisse to Today, at the 2020 Annual Conference in Chicago. Photo: Stacey Rupolo

CAA invites nominations and self-nominations for individuals to serve on our Awards for Distinction, Publication Grant, Fellowship, and Travel Grant juries. Terms begin August 2020.

Candidates must possess expertise appropriate to the jury’s work and be current CAA members. They should not hold a position on a CAA committee or editorial board beyond May 31, 2020. CAA’s president and vice president for committees appoint jury members for service.

Awards for Distinction Juries

CAA has vacancies in ten of the fourteen juries for the annual Awards for Distinction for three years (2020–23). Terms begin in August 2020; award years are 2021–23.

- Alfred H. Barr Jr. Award for museum scholarship in the history of art/Alfred H. Barr Jr. Award for Smaller Museums, Libraries, Collections, and Exhibitions for museum scholarship in the history of art published by smaller institutions: two vacancies

- Frank Jewett Mather Award for art criticism: two vacancies

- Charles Rufus Morey Book Award for non-catalogue books in the history of art: one vacancy

- Arthur Kingsley Porter Prize for articles written by younger scholars in The Art Bulletin: one vacancy

- Artist Award for Distinguished Body of Work: two vacancies

- Distinguished Artist Award for Lifetime Achievement: one vacancy

- Distinguished Feminist Awards for Scholars and Artists: one vacancy

- Distinguished Teaching of Art History Award: one vacancy

- Excellence in Diversity Award: four vacancies

Publication Grant Juries

CAA has vacancies on our Millard Meiss Publication Fund grant jury for four years (2020–24) and the Terra Foundation for American Art Publication Grant jury for one year (2020-21).

- Millard Meiss Publication Fund: three vacancies

- Terra Foundation for American Art Publication Grant: one vacancy

Professional Development Fellowship Juries

CAA has vacancies on our Professional Development Fellowship juries for three years (2020–23). Terms begin August 2020.

- Professional Development Fellowship in Visual Arts: three vacancies

- Professional Development Fellowship in Art History: two vacancies

Travel Grant Juries

CAA has vacancies on our Art History Fund for Travel to Special Exhibitions jury for three years (2020–23). Terms begin August 2020.

- Art History Fund for Travel to Special Exhibitions: two vacancies

HOW TO APPLY

Nominations and self-nominations should include a brief statement (no more than 150 words) outlining the individual’s qualifications and experience and a CV (an abbreviated CV no more than two pages may be submitted). Please send all materials by email to Cali Buckley (cbuckley@collegeart.org), CAA grants and special programs manager; submissions must be sent as Microsoft Word or Adobe PDF attachments.

For questions about jury service and responsibilities, contact Tiffany Dugan (tdugan@collegeart.org), CAA director of programs and publications.

Deadline: July 31, 2020

Join a CAA Professional Committee

posted by CAA — Jun 15, 2020

Artist Jill Odegaard (left) and participant work on Woven Welcome as part of ARTexchange at the 2020 Annual Conference, an event organized by CAA’s Services to Artists Committee. Photo: Stacey Rupolo

Call for applicants to CAA’s Professional Committees (for term 2021-2024)

The Professional Committees address critical concerns of CAA’s members. Each Professional Committee works from a charge that is put in place by the Board of Directors. Committee members serve three-year terms, with the term of service beginning and ending at the CAA Annual Conference. Candidates must be current CAA members, or be so by the start of their committee term and possess expertise appropriate to the committee’s work. All committee members volunteer their services without compensation. It is expected that once appointed to a committee, a member will attend committee meetings (including an annual business meeting at the conference), participate actively in the work of the committee, and contribute expertise to defining the current and future work of the committee. For many CAA members, service on a Professional Committee becomes a way to develop professional relationships and community outside of one’s home institution, and to contribute in meaningful ways to the pressing professional issues of our moment.

The following Professional Committee are open for terms beginning in February 2021. Please click on the links in order to review the charge of each committee, as well as the roster of current committee leadership and members:

- Committee on Design

- Committee on Diversity Practices

- Committee on Intellectual Property

- Committee on Research and Scholarship

- Committee on Women in the Arts

- Education Committee

- International Committee

- Museum Committee

- Professional Practices Committee

- Services to Artists Committee

- Services to Historians of Visual Arts Committee

- Student and Emerging Professionals Committee

Committee applications are reviewed by the current committees, as well as CAA leadership (CAA’s President, the Vice President for Committees, and Executive Director). Appointments are made by late October, prior to the Annual Conference. New members are introduced to their committees during their respective business meetings at the Annual Conference in February 2021 in New York City.

In applying to serve on a committee, applicants commit to beginning a term in February 2021, provided that they are selected for committee service.

Prospective applicants may direct logistical questions to Vanessa Jalet (vjalet@collegeart.org). Questions about the committee charge and current work to the current committee chair and/or to the Vice President of Committees: Julia Sienkewicz (julia.a.sienkewicz@gmail.com)

Self-nominations should include a brief statement (no more than 150 words) describing your qualifications and experience, combined with an abbreviated CV (no more than 2–3 pages). These two items should be forwarded in a single PDF document emailed to: vjalet@collegeart.org

Deadline for applications: Monday, August 31, 2020

Kindly enter subject line in email: 2021 Professional Committee Applicant

News from the Art and Academic Worlds

posted by CAA — Jun 10, 2020

|

|

|

|

|

Want articles like these in your inbox? Sign up for our weekly newsletter:

News from the Art and Academic Worlds

posted by CAA — Jun 03, 2020

A makeshift memorial and mural by local artists to honor George Floyd, Minneapolis, Minnesota. Photo: Kerem Yucel/AFP, via CNN

|

|

|

|

|

|

Want articles like these in your inbox? Sign up for our weekly newsletter:

News from the Art and Academic Worlds

posted by CAA — May 20, 2020

The managing horticulturist at the Met Cloisters, Marc Montefusco. Photo courtesy of Marc Montefusco, via artnet News

|

|

|

|

|

Want articles like these in your inbox? Sign up for our weekly newsletter:

An Interview with Suzanne Preston Blier on CAA’s Code of Best Practices and Publishing with Fair Use

posted by CAA — May 19, 2020

In 2019, Suzanne Preston Blier, professor of African art at Harvard University and former president of CAA, published a major book on Picasso’s use of global imagery, Picasso’s Demoiselles: The Untold Origins of a Modern Masterpiece. In addition to its scholarship the book is groundbreaking for its reliance on fair use, the principle within US copyright law that permits free reproduction of copyrighted images under certain conditions. CAA led the way among visual arts groups in calling for reliance on fair use, producing in 2015 its Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts.

In 2019, Suzanne Preston Blier, professor of African art at Harvard University and former president of CAA, published a major book on Picasso’s use of global imagery, Picasso’s Demoiselles: The Untold Origins of a Modern Masterpiece. In addition to its scholarship the book is groundbreaking for its reliance on fair use, the principle within US copyright law that permits free reproduction of copyrighted images under certain conditions. CAA led the way among visual arts groups in calling for reliance on fair use, producing in 2015 its Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts.

In this interview with Patricia Aufderheide, university professor and founding director of the Center for Media & Social Impact (CMSI) at American University, and a principal investigator in the CAA fair use project, Blier relates how she became an inadvertent pioneer of fair use in art history.

An Interview with Suzanne Preston Blier, Harvard University

By Patricia Aufderheide, American University

I met Prof. Blier, an award-winning art historian, when CMSI joined others in facilitating the Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts for the College Art Association (CAA), with funding from the Samuel H. Kress and Andrew W. Mellon Foundations. Fair use is the well-established US right to use copyrighted material for free, if you are using that material for a different purpose (such as academic analysis, for instance) and in amounts relevant to the new purpose. Blier was the incoming president, as the Code launched.

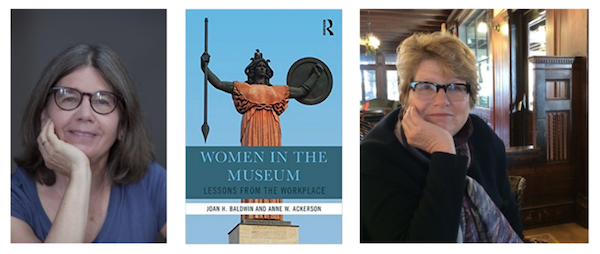

The project addressed a huge need. Art historians, visual artists, art journal and book editors, and museum staff all have faced major hurdles in accomplishing their work because of copyright. Art historians avoided contemporary art in favor of analyzing public domain material. Visual artists hesitated to undertake innovative projects that reuse existing cultural material. Editors, or sometimes their authors, faced monumental bills for permissions and sometimes those permissions depended on an artist or artist’s estate agreeing with what they say. Museums hesitated to do virtual tours, or use images in their informational brochures, or even to mount group exhibits, because of prohibitive permissions costs. All together, some people in the visual arts called this “permissions culture.”

Once the Code came out, some things changed immediately. Museums rewrote their copyright use policies. Artists made new work. CAA’s publications—some of the leading journals in the field—adopted fair use as a default choice.Yale University Press prepared new author guidelines for fair use of images in scholarly art monographs to encourage fair use. Blier was one of the Code’s champions.

And then she needed it herself. As she began work on her most recent book, which ultimately resulted in Picasso’s Demoiselles: The Untold Origins of a Modern Masterpiece (Duke University Press, 2019, winner of the 2020 Robert Motherwell Book prize for an outstanding publication in the history and criticism of modernism in the arts by the Dedalus Foundation), she realized the subject faced the stiffest possible copyright challenge. To tell her story, she would have to be able to show images from a variety of artists, most challengingly, Picasso. She thought of Duke University Press, a publisher that has been willing to go ahead of others on fair use. So Blier approached them. Duke was very supportive, and they ended up hiring extra legal counsel for this. In the end, Blier said, she had to rewrite certain sections, and redo some images at the suggestion of outside counsel, to strengthen the fair use argument.

Blier tells the story of how the book got out into the world (and won an award), below.

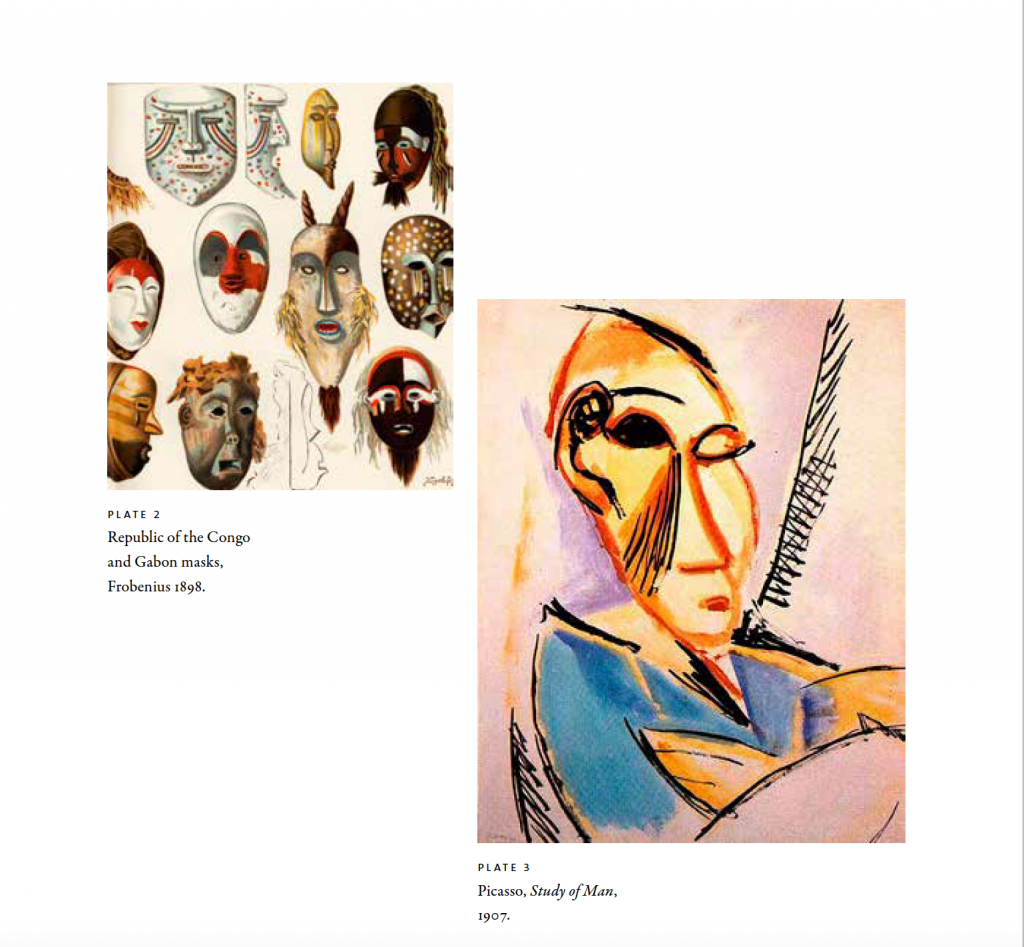

Figure 1. Congo masks published in Leo Frobenius’ 1898 Die Masken und Geheimbünde Afrikas alongside Pablo Picasso’s Study of Man (1907). The Congo mask at the bottom, second from the left is the likely source for the crouching demoiselle. The mask at the top left shows tear lines from the eyes crossing diagonally down the cheeks similar to Picasso’s preliminary study for one of the men in an early compositional drawings for the canvas.

You’re an expert in African art. How did you end up writing a book about one of the most famous modernist artists?

This is a book I never intended to write; it found me. For my previous book, Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba: Ife History, Power, and Identity, I was doing those last-minute bits of work in the library to check sources, and I pulled out a book adjacent to the book I was looking for, an old book by the German anthropologist, Leo Frobenius. I hadn’t read it since graduate school. As I opened it up, I looked down and I said, Wow, this is a book on African masks and they look like they’d be the ones Picasso used as models for his famous 1907 painting Demoiselles d’Avignon. At the time I had first read the book, Picasso’s drawings for the painting hadn’t been released. This time I saw it differently and as I was looking at it in the library, I saw there was tracing paper over the pictures. There was a line drawing covering each mask, and that seemed significant too.

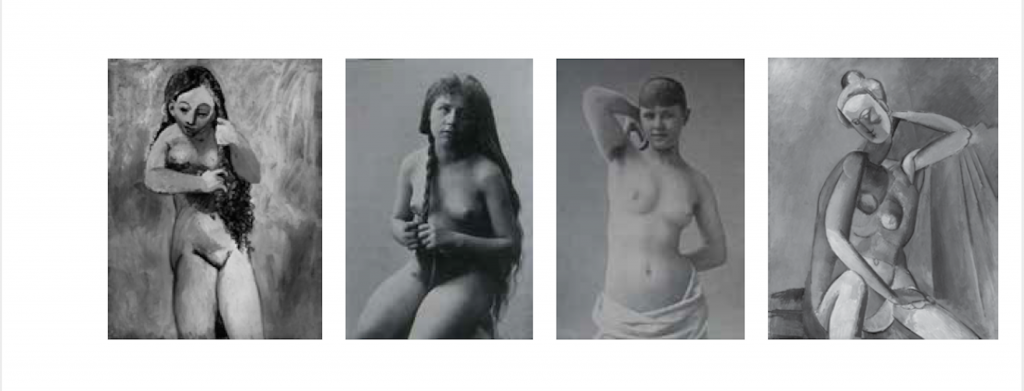

The next thing I knew, I was hunting for a book from the Harvard library on Dahomey women warriors. It turned out it was in the medical school library, which should have been a sign. When I picked it up at the main library and flipped it open, I thought, Oh my god, it’s pornography! It was photos and line drawings of women around the world, in supposed “evolutionary” order. Photos of naked women begin with so-called “archaic,” in Papua New Guinea, right through to southern Europe, then Denmark. In the library I’m bending over, kind of hiding it, out of embarrassment. I bring it home and realize, Ohhhh! Here’s another key source for Demoiselles. This volume, which was by Karl Heinrich Stratz, had gone through multiple editions, and one was published about the same time Picasso stopped using living models. Then I found another book, by Richard Burton, which had a rendering that Picasso clearly used for his 1905 sketch Salomé.

What happened next was the clincher. I went to Paris to lecture at Collège de France. The week before my lectures, I went to hear another speaker at the Collège, a medieval historian. One of the first slides he presented was a work from a medieval illustrator, Villard De Honnecourt. This book was a modern edition of an illustrated medieval manuscript, published in the right time frame for Picasso to have seen it. And I thought, Well, here’s another source Picasso used.

Later I was also able to rediscover a photo that allowed me to date the painting to a single night in March 1907. The scene is often identified as a brothel, but bordel in French doesn’t mean bordello, but rather a chaotic or complex situation. It was my belief that Picasso was creating a time-machine kind of image of the mothers of five races, as he understood them from the Stratz ethno-pornography book and other sources, each depicted in the art style of that region or period. My larger argument is not only that Picasso was using book illustration sources, but also that these books invite us to see the canvas in a new light, and that, for Picasso, the painting has its intellectual grounding in colonial-era ideas about human and artistic evolution.

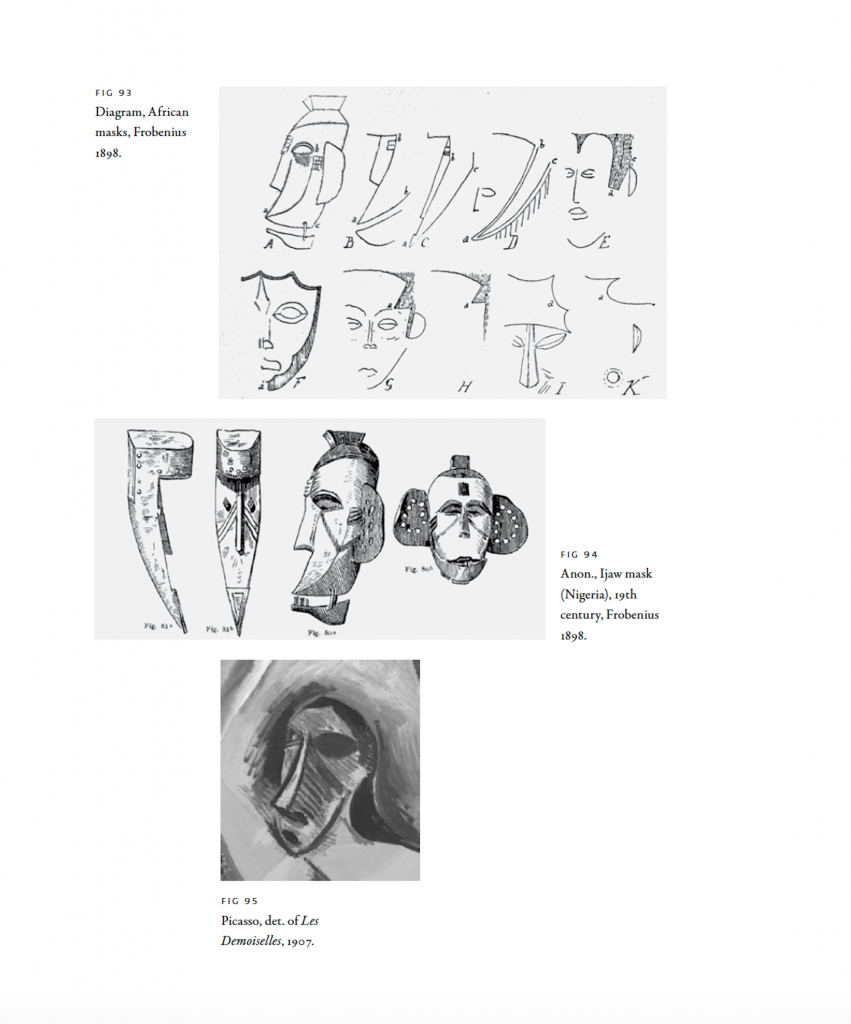

Figure 2. Illustrations from Leo Frobenius’ 1898 Die Masken und Geheimbünde Afrikas showing (top two rows) the visual development of a mask into a human face. The middle illustration ,from the same Frobenius book shows line drawings of ijaw masks from Nigeria. The bottom image is a detail of the standing African figure from Picasso’s 1907, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon which appears to be based on a combination of these two masks.

What a sleuthing job! And so you decided to write the book then?

I wrote the first two chapters while I was in Paris doing the lecture. I saw it not as a coffee-table art book, but the kind of book you put in your knapsack as you head off to a long ride on the subway.

It was easy to write, but it was a very different story for the images. I immediately got a trade publisher in Britain to agree to publish it, and then they said they could not do it, because of problems getting permission to reproduce images from the Picasso Foundation.

The Picasso Foundation is notorious for making it difficult to access Picasso images, isn’t it?

The price of permissions is high, and this Foundation like many estates is interested in guarding the artist’s reputation as well. The difficulties of publishing on Picasso have been manifested in how little publishing was being done, and how scarce the images were in that work. Since 1973, there have been few heavily illustrated books about Picasso, except by wealthy individuals or museums in relation to an exhibition. I had heard about Rosalind Krauss publishing a work without permissions—at least that’s what I heard—anyway, she used very few images. Leo Steinberg apparently had not been able to arrange the rights for a work he wanted to do, a book edition of his two seminal articles on Les Demoiselles.

Although I hadn’t realized it until recently, in September 2019 there was an important case in the US, about a set of illustrated books by Christian Zervos with a wide array of Picasso illustrations. The case was started in France, but a US judge has allowed fair use.

But generally, yes, there’s common wisdom among art historians that the Picasso Foundation is a formidable challenge.

So how did you proceed when the first publisher backed out?

I was disheartened, but I got an agent. He sent it off to ten or twelve trade publishers worldwide—and came up with nothing.

Then I realized I was going to have to go to a university press. That was a big decision. The trade publication will pay for the images, and do all the work on the rights clearance. But with a university press, you’re on your own.

One of the first people I contacted was legendary editor Ken Wissoker at Duke University Press. He was interested, but then came the issue of the images. I may have broached fair use with him from the start. The manuscript had gone through peer review and it was in great shape except for this copyright issue. I had quite a number of images—in the end, it was 338. At Duke, they won’t begin the editorial process until you have all the copyright clearances on images done. So I began the difficult process of deciding how to get the images.

Were you in contact with the Picasso Foundation directly?

I did contact them, in order to let them know about the project in general. I was doing final research work in Paris. I had framed the book as a travelogue in part addressing my discovery of these sources. I also wanted to find out so much more about Picasso. I’m not a modernist, I’m an outsider to the field. So I worked hard to get as much insight and criticism of the manuscript from specialists as I could.

I made it a point to meet with people at the Picasso Foundation. I had a Powerpoint of the images, which I showed to one of the key people there. Later I wrote to them, “here’s the manuscript, let me know if you have any thoughts.” And I heard nothing back. I had heard that with some manuscripts, they have been concerned one way or another. I didn’t want their permission for the intellectual content, but since they knew this artist and his life and family better than any academic could, I wanted their insights.

And then you started to look for permissions?

Well, I began to think about the cost of acquiring the images. The process is such that you have to go through the Artists Rights Society (ARS, a US licensing broker). And to get a price, you have to furnish the number of images, how many are color, the size of the print run, the prospective profit, and a whole series of things we could not know. Duke wouldn’t even look at the project editorially without having the rights in hand. I had heard difficult stories—that they were interested in looking at the galleys along the way, and requesting changes, for quality control, but it wasn’t possible to do this and work with the press.

If I had to guess, I would say that it might have cost me something like $80,000 of my own money to purchase the minimum number of images for this scholarly book, from which I expect to make no money, or very little.

Figure 3 from left to right: Pablo Picasso, Nude Combing Her Hair, 1906; Girl braiding hair from C. H. Stratz, La beauté de la femme, 1900 (Paris); Girl from Vienna from C.H. Stratz, La beauté de la femme, 1900; Picasso Seated Female Nude, 1908. Over the course of his long career Picasso would continue to use key visual insights from Frobenius, Stratz, and other illustrated sources he was exploring in this late 1906 to early 1907 period.

So how did you come to the decision to use them under fair use?

I had been president of CAA in 2016-17, and a longtime promoter of fair use and IP issues more generally. I was involved in the creation of the Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts. For me, CAA’s role in fair use is one of the most important and radical (in a positive way) things that it has ever done.

I decided that fair use would make the most sense in this context. This was a book about an important modern artist. In addition, I’m a senior scholar—this was not my first publication. If the worst happened, if I had problems, well, I’ve had a great career and this would not harm it. I have tenure and so on. Also, as the then-president of CAA, I thought it was important to do this.

Besides, this to me was part of a larger picture of what I had done in my larger career. I’m very active locally in civic affairs, and really interested in promoting transparency, and democratic ideals. I was also very fortunate to have Peter Jaszi, a foremost legal scholar on fair use (and another principal investigator on the CAA project), working with me. At his suggestion, I took out an insurance policy, which for a fee—I think about $5,000—(with a $10,000 deductible) I was able to lower my anxiety level. I also paid $400 for an attorney to look over the insurance contract. And I had good friends like you, who when I got cold feet assured me it was the right thing to do. And of course, Duke is a publisher that has been willing to go ahead of others on fair use.

Can you give me an example of something you had to change in the text to strengthen the fair use argument?

With a museum photograph of an African mask, for example, I had to explain why this particular way of photographing the work was critical to the argument in my book. I had to ad a few sentences to justify my selection of several Picasso works as well. I also had to give reasons in my text for why each of the chapter epigraphs was necessary.

Did you have to alter the use of imagery in any way to accommodate fair use?

There are changes the press made, design-wise, that reflected in part the decision to employ fair use. Many of the photos are shown in black-and-white and the majority are reduced in size. I was constrained by the fact that I could only employ fair use if I could get access to the materials without going through the Picasso Foundation. So I had to acquire nearly all the images from published books, and many of the Picasso images were published in black and white and at a very small size, in a grainy context. I had to spend a lot of time hunting down the best possible images to use. In my book they are shown in relatively small size, along with information on where you can find color versions online.

That didn’t bother me too much, though. For readers and viewers at this juncture in the Internet era, we have become expert at extrapolating the fuller figure from a small image.

There is also a small spread of color images, a couple Picasso works as well as from other artists. For these images color was central to the book.

The decision to publish largely in black-and-white was, I think, also related to the fact that the Picasso Foundation and others are concerned that color representations be incredibly accurate, and it is very hard to get the color exactly right, when copying from books. You also have an issue with paper quality in getting accurate representation.

The cover is a handsome design, and very clever. They broke up the images into thumbnail-like sections, requiring you as a viewer to put them together as one image, similar to how Picasso was thinking in the early stages of cubism, where you as a viewer of an assemblage have to assemble them in your own mind, to make it work for you as a whole.

How was the book received?

It was a finalist for the Prose Prize, a prize of publishers to authors. My previous book won it in 2016. I didn’t expect to win it this time again, in 2019. I was very honored that it was a finalist. It was also featured in the Wall Street Journal’s holiday art book list. And then, just recently, it won the Robert Motherwell Book Award.

Has the Picasso Foundation seen the book?

To date I’ve heard nothing. I was thinking earlier that the Picasso Foundation might want to stop it pre-publication. So much so that when I came back from travel in Africa, I went first to my academic mailbox, and was relieved when I saw no big legal envelope. But there has been no pushback. I certainly gave them the opportunity to comment on the content while it was still in manuscript. And last April or May, I went to France to meet with the curators at Musée Picasso about contributing an essay to a catalog. I sent them an article draft which they decided not to publish, which is fine, but also sent them a copy of the manuscript, and of course the Musée speaks to the Foundation.

Interestingly, the two cases where the Foundation has sued or prevented publication that I know of have to do with children’s books about Picasso. I don’t know what that means.

Does the wider art history community know about this?

I hope this personal story makes a difference. We still have a lot of educating to do, in spite of the work we did around the Code. I continually get, on the art history listservs, questions—How can I get permission, and I always say, Use fair use. People still don’t trust it or believe it’s more difficult than it is.

At the CAA conference I just went to in Chicago, there seems to be a division between presses. Presses at private universities–Yale, Princeton, MIT, Duke—seem to feel more comfortable exploring this. But for university presses at some public institutions, these legal issues have to be taken up with the state attorney general, and there can be real nervousness stepping outside a narrow parameter. I learned this speaking to an editor at a state university press in a progressive state, who believes they’re being held back because of this fear.

I was pleased to see at this same conference a pamphlet on fair use by Duke University Press’s former Director, Steve Cohn. In his essay, he mentions my Picasso book and how happy he is that Duke chose to publish it this way. I figured, if Steve is openly talking about this fair use project, then the proverbial cat is out of the bag, and I could be more open and provide some of the back story from my end.

CAA’s scholarly publications, The Art Bulletin, Art Journal, and Art Journal Open rely on fair use as a matter of policy, and indicate when they do so in their photo credits. View a complete discussion of fair use and CAA’s Code of Best Practices.

News from the Art and Academic Worlds

posted by CAA — May 13, 2020

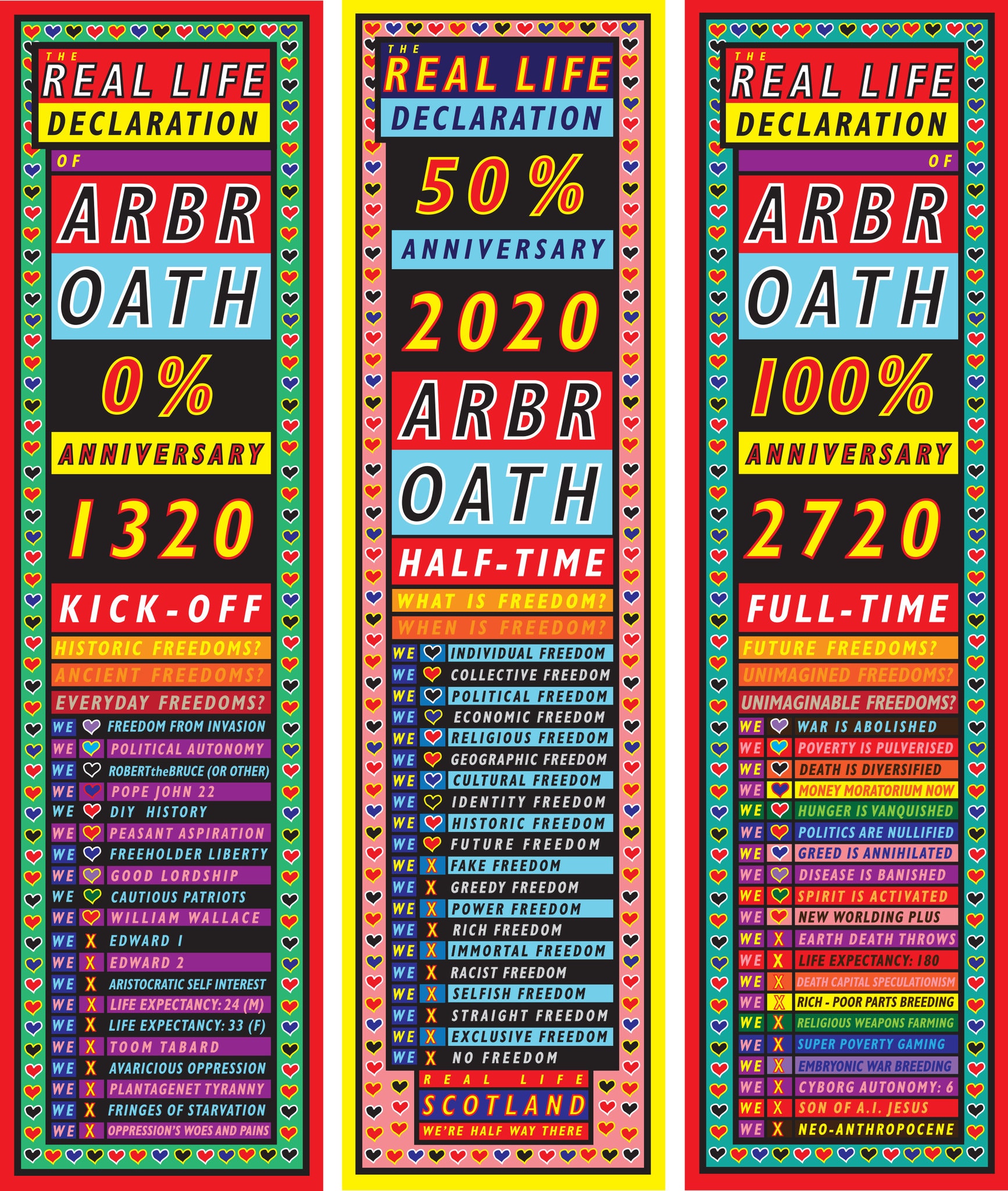

Ross Sinclair’s The Real Life Declaration of Arbroath 1320–2720, 2020, one of the works in the Royal Scottish Academy’s annual exhibition, which went entirely online because of the pandemic. Image: Royal Scottish Academy, via New York Times

|

Want articles like these in your inbox? Sign up for our weekly newsletter:

Announcing the 2020 Recipients of the Art History Fund for Travel to Special Exhibitions

posted by CAA — May 12, 2020

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

In fall 2018, we announced CAA had received an anonymous gift of $1 million to fund travel for art history faculty and their students to special exhibitions related to their classwork. The generous gift established the Art History Fund for Travel to Special Exhibitions.

The jury for the Art History Fund for Travel to Special Exhibitions has now selected the second group of recipients as part of the gift. This year’s awardees are:

Holly Flora, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA

Course: Art, Cosmopolitanism, and Intellectual Culture in the Middle Ages

Exhibition: Medieval Bologna: Art for a University City at the Frist Center for the Visual Arts, Nashville, TN

Caroline Fowler, Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA

Course: Slavery and the Dutch Golden Age

Exhibition: Slavery at the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Maile Hutterer, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR

Course: Time in Medieval Art and Architecture

Exhibition: Transcending Time: The Medieval Book of Hours at The Getty Center, Los Angeles, CA

Erin McCutcheon, Lycoming College, Williamsport, PA

Course: Art & Politics in Latin America

Exhibition: Rafael Lozano-Hemmer: Unstable Presence at SFMOMA, San Francisco, CA

Shalon Parker, Gonzaga University, Spokane, WA

Course: Women Artists

Exhibition: New Time: Art and Feminisms in the 21st Century at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Berkeley, CA

Rebecca Pelchar, SUNY Adirondack, Queensbury, NY

Course: Introduction to Museum Studies

Exhibition: Marcel Duchamp: The Barbara and Aaron Levine Collection at the Hirshhorn Museum, Washington, DC

As museums and schools have moved online in light of the coronavirus pandemic, we are being as flexible as necessary with the dates of travel to accommodate all award winners and classes.

The Art History Fund for Travel to Special Exhibitions supports travel, lodging, and research efforts by art history students and faculty in conjunction with special museum exhibitions in the United States and throughout the world. Awards are made exclusively to support travel to exhibitions that directly correspond to the class content, and exhibitions on all artists, periods, and areas of art history are eligible.

Applications for the third round of grants will be accepted by CAA beginning in fall 2020. Deadlines and details can be found on the Travel Grants page.