CAA News Today

International Review: Gordon Walters: New Vision by Leonard Bell

posted by CAA — Dec 06, 2018

The following article was written in response to a call for submissions by CAA’s International Committee. It is by Leonard Bell, professor of art history, University of Auckland, New Zealand.

Exhibition and catalogue review: Gordon Walters: New Vision, Dunedin Public Art Gallery, 11 November 2017- 8 April 2018, and Auckland Art Gallery, 7 July – 4 November 2018.

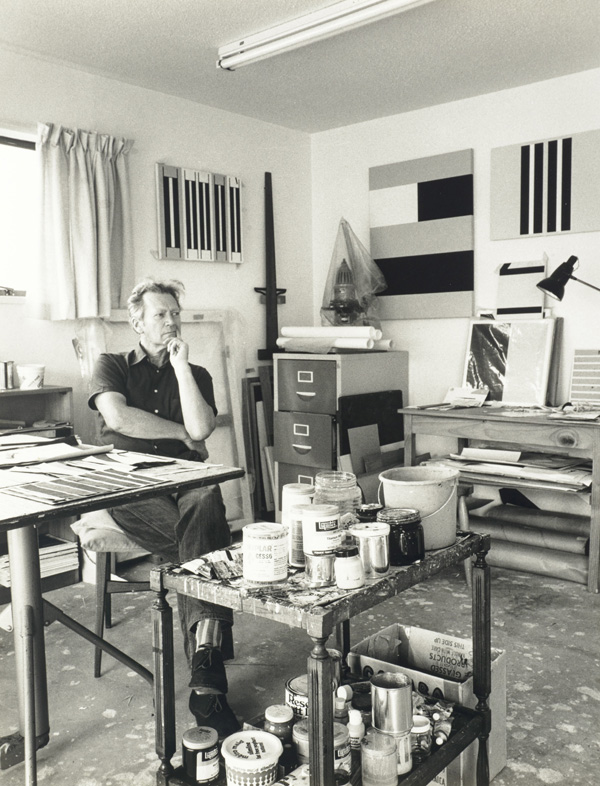

Marti Friedlander, Portrait of Gordon Walters in His Studio, 1978, Marti Friedlander Archive, EH McCormick Research Library, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, Courtesy Gerrard and Marti Friedlander Charitable Trust.

The much-lauded work of Gordon Walters (1919-1995), one of New Zealand’s first geometric abstract painters, has also generated controversy. A retrospective show traveled the country in 1983, but the present exhibition is the first comprehensive survey of Walters’s complete oeuvre from the late 1930s until his last painting in 1995. A wonderful show, curated by Lucy Hammonds, Laurence Simmons, and Julia Waite, it clearly establishes Walters’s greatness as a painter. Walters’s art was informed and sustained by an extensive knowledge and sophisticated understanding of Euro-American—Piet Mondrian (principally), Sophie Tauber-Arp, Joseph Albers, Auguste Herbin and John McLaughlin, for instance—and Oceanic art, in particular the koru motif of Maori kowhaiwhai (painting, on rafters and paddles, for example) and moko (tattoo). Add to those his early, unusual-in-New Zealand interest in Surrealism and the idiosyncratic sketches of a mentally ill man, Rolf Hattaway. Walters learned about these from a close friend, émigré Dutch artist Theo Schoon, an ardent advocate of Bauhaus practices and Maori visual arts, especially “primitive” rock art.

The resultant body of work constitutes an imaginative and distinctive interweaving of elements from diverse societies and cultures. Formally and technically rigorous, visually refined, conceptually deep, Walters’s paintings are both still and tense. While pulling in different directions, his best known work, the so-called koru paintings, somehow betoken their place, a cluster of islands in the southwest Pacific. Their imprint extends far beyond the art world, to the New Zealand Film Commission’s logo, for instance. Yet, to present Walters’s art only in terms of these koru paintings would skew the overall picture and leave it incomplete. The exhibition rightly gives as much attention to his many other different paintings.

Sydney Parkinson, painted Maori paddle, 1769, Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology, University of Cambridge, UK.

Since Walters’s breakthrough shows at Auckland’s New Vision Gallery in 1966 and 1968 (his first since an early exhibition in 1949), writings about his art have proliferated. His abstractions attracted the keen attention not only of New Zealand art historians, critics, and philosophers, but also the eminent British critic Robert Melville (Architectural Review, 1968), who regarded Walters’s paintings as the best he encountered in New Zealand, polymathic Ernst Gombrich (The Sense of Order, 1979), as well as Australian art historians Rex Butler and A. D. S. Donaldson, and American Thomas Crow (in the present catalogue). The handsome publication reproduces a rich feast of Walters’s works. Nine writers produced eight essays exploring various aspects of Walters’s art and career. Several essays (notably by Peter Brunt and the Australians) offer new details and connections between Walters and other artists.

The trajectory of his career, his primary inspirational sources, his paintings’s formal qualities and conceptual substance, though, have already been intensively excavated, especially by Michael Dunn in the 1970s and 1980s, and Francis Pound from the mid-1980s until his death in 2017.

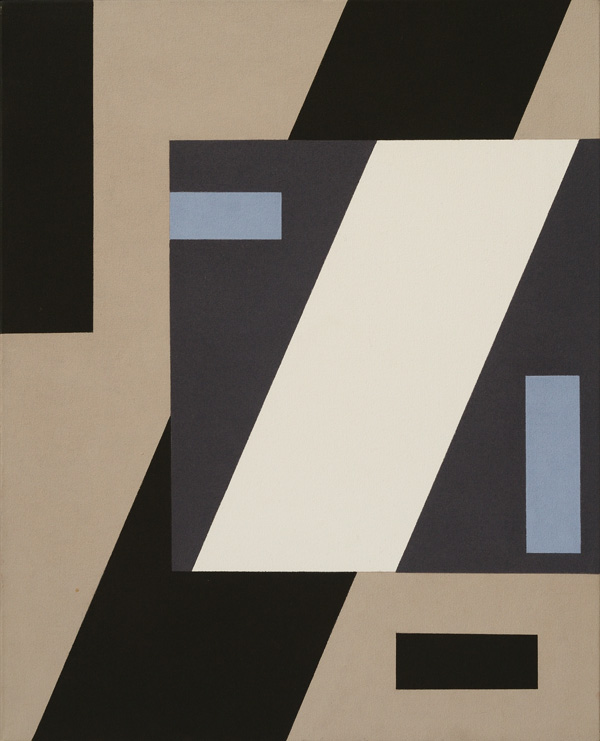

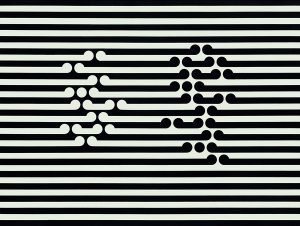

Gordon Walters, Untitled, 1989, Collection James Wallace Arts Trust, gift of the Rutherford Trust.

In an exhibition review in Art News New Zealand (Summer, 2017), David Eggleton observed, “Curiously, Pound is an absent if also an insistent presence in the catalogue of the show. Although not included as a contributor, many of the ideas and notions first proposed by him appear in the text, subsumed into the writings of others.” And a festschrift in 1989 to mark his 70th birthday, Gordon Walters: Order and Intuition, edited by James Ross and Laurence Simmons, had ten scholarly essays, including (disclosure) my “Walters and Maori Art: the nature of the relationship?”

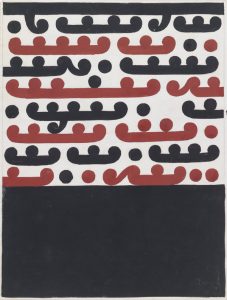

Transformation of his inspirational sources characterizes Walters’s art. His first investigations of the Maori koru motif, small studies in ink and gouache, appeared in the mid-1950s. They were close to the source; the motif’s organic quality was semi-retained.

In the mid-1960s Walters geometricized the form. Except for circular shapes terminating the crisply delineated bars, curves were straightened out. The reshaped element provided a means, in league with Mondrian et al, for studies in formal relationships using a “deliberately limited range of forms” (Walters, 1966).

These were not intended to draw on the Maori motif’s symbolic values, though Walters’s use of Maori terms for many titles was an acknowledgement of the inspirational importance of Maori art as he had experienced it.

From the mid-1980s, most forcefully in the 1990s, possibly triggered by critiques leveled at the Museum of Modern Art’s 1984-1985 exhibition, Primitivism: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern, Walters was accused of exploitative appropriation of Maori art by several critics, both Maori and Pakeha (European New Zealander).

Gordon Walters, Gouache, 1957-8, Hocken Collections Uare Taoka o Hākena.

Others, including Maori and Pakeha artists, also defended Walters. The catalogue touches on this sometimes acrimonious argument, though the exhibition’s wall texts and captions bypass it. Deidre Brown’s catalogue essay, “Pitau, Primitivism and Provocation: Gordon Walters’ Appropriation of Maori Iconography,” steers a near-neutral path between the antagonists, culminating with the claim that they moved onto other concerns: “the appropriation debate faded away from academic art history.” Several reviewers, though, questioned whether the contentious issue was satisfactorily addressed by the show.

Most of Walters’s detractors and advocates assumed a straightforward relationship between his work and Maori art: cause = koru motif and effect = the forms in Walters’s koru paintings. The detractors appeared to subscribe to a Manichean structure of polarities in which modernist borrowings are, ipso facto, “bad.” In this system a single component in the works becomes the only or dominant one. If the same paintings are seen within wider cultural and historical contexts, though, an interplay of multiple elements and global connections, in which no single one is dominant, becomes manifest. A complex of factors also mediates how Walters’s koru paintings have functioned. Depending on the kinds of knowledge and cultural baggage individual viewers bring to the encounter, they are clearly perceived very differently. Indeed, one could well wonder whether viewers with opposing perspectives are talking about the same pictures. The diverse opinions resist resolution; the conflicting perspectives are incommensurable. Just as creationists are unlikely to accept a logical refutation of the existence of “God,” so Walters’s critics are not likely to see his art in any other way than their own.

Gordon Walters, Painting No. 1, 1965, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, Purchase 1965.

Take another slant. In 1910 the New Zealand Herald reported a “curious discovery” by Mme Boeufvre, wife of New Zealand’s French consul. Seeing the Book of Kells (c. 800 CE) in Dublin, she “was much struck by the similarity of Celtic ornaments to Maori conventional designs…how very closely the Maori patterns resembled those of the ancient artists of Ireland.” Since the nineteenth century parallels were frequently drawn between curvilinearities in Maori artifacts and those in the art and ornament of other societies, including such varied cultures and aesthetics as Egyptian, Greek, South East Asian, Victorian, and Art Nouveau, in addition to Celtic. For instance, renowned Austrian art historian Alois Riegl (‘Neuseelandische Ornamentik’, 1891, and Stilfragen, 1896) matched Maori and Egyptian spiraling forms. He noted that they could not possibly have had the same origin. Like many other forms, that of the swastika, for example, the form of the Maori koru motif is found all over the world. There is no singular point of invention.

Universal and local collide in Walters’s painting. Was Walters indigenizing the modern or modernizing the indigenous—or both, or neither? Can we look through several lenses simultaneously? Compelling art certainly can emerge from socio-cultural dissonance—Walters’s paintings continue to energize the spaces they inhabit. They have a contemporary urgency, informing the work of contemporary artists of both Pakeha and Maori descent, such as Darren George and Chris Heaphy. (The latter worked with Walters in his last years.) For others tension between Maori and Euro-American aesthetics and practices remains. Walters’s painterly synthesis of Maori, Oceanic, European, and American elements and ideas was virtually unique among Pakeha artists in his time. He trod a solitary path. In retrospect, though, his oeuvre constitutes a crucial watershed, in which the possibilities of bicultural coexistence of things Maori and Pakeha were explored, celebrated and contested.

Gordon Walters, Untitled, 1972, Dunedin Public Art Gallery Loan Collection, Courtesy of the Gordon Walters Estate.

CWA Picks for December 2018

posted by CAA — Dec 04, 2018

Installation view of Leonor Fini: Theatre of Desire, 1930-1990, on view at the Museum of Sex through March 4, 2019.

CAA’s Committee on Women in the Arts selects the best in feminist art and scholarship to share with CAA members on a monthly basis. See the picks for December below.

CONTRIBUTION TO LIGHT: THE EARLY WORKS OF BARBARA HAMMER

September 13, 2018 – January 31, 2019

Kow Madrid

Barbara Hammer needs no introduction. One of the first filmmakers to openly address and document lesbian sexuality, Hammer is both a feminist pioneer of queer cinema and an influential force of avant-garde and experimental filmmaking. She is also dying.

In a recent talk at the Whitney Museum (The Art of Dying or [Palliative Art Making in the Age of Anxiety]) she frankly, movingly, and inspiringly spoke of death and (her) art, living with cancer and one’s right to die “when she wishes,” advocating terminally ill patients’ right to decide how and when to die. Concentrating instead on works that precede the specter of death in her work, Contribution to Light focuses only on very early films, photographs, and works on paper, including some previously unknown. It seeks to explore the role physical perception of space and relationships play in Hammer’s first steps as an artist, marking the signature combination of physical presence, painterly quality, and sensual expressionism that characterizes much of her work both on celluloid and paper. “Her camera gaze seems to literally touch the environment, inseparable from her body and its experiences, while her paint brush and her pencil are unafraid to discern the surface of the paper as a field of action and mental and formal discovery,” as put in the press release. Touch has been indeed central in Hammer’s vision, and she eloquently speaks about it during the aforementioned talk. While this show in Madrid is only a small homage to Hammer’s beginnings, her illness and own commitment to prepare for the aftermath of her death has already precipitated a wave of much-needed study, preservation, and celebration of her work in the US. A major retrospective will open next summer at the Wexner Center for the Arts. But will she be alive, or conscious to see it? Wishing so, this CWA selection symbolically reciprocates her loving goodbye while she is still in life.

Tomie Ohtake: At Her Fingertips

November 1 – December 22, 2018

Nara Roesler Gallery, New York

This concise exhibition focuses on Tomie Ohtake’s preparatory collages, drawings, and engravings from the 1960s and 1970s and proposes a new dimension to the Japanese-Brazilian artist’s expansive, six-decade career and legacy. Curated by Paulo Miyada, chief curator of the Instituto Tomie Ohtake, São Paulo, At Her Fingertips places Ohtake’s “studies” in direct relationship to a few select paintings, arguing for a dynamic reciprocity between media and offering further insight into the eminent artist’s approach to abstract gesturalism, geometry, and spirituality. These small, colorful collages—torn and ripped somewhat haphazardly—are hung directly from the ceiling in double-sided glass frames, highlighting the graphic and material nature of paper cutouts and promoting the dialectics of chance and control underlying Zen Buddhism and Japanese calligraphy. This tidy show further informs the interwoven dialogues on abstraction offered in postwar Brazil from which Ohtake readily drew upon, including those by the Seibi group’s second generation, including Manabu Mabe and Flávio-Shiró, and the Concrete principles of design and color theory by Wyllis de Castro and Hércules Barsotti, for example. In all, this exhibition continues the important historical work on Ohtake, and delivers a morsel of her brilliant career to a new audience in New York.

LINDA VALLEJO: AMERICAN Latinx

September 4 – December 14, 2018

Kean University Karl and Helen Burger Gallery, Union, New Jersey

Linda Vallejo provokes both directly and subtly poignant questions through her “Make ‘Em All Mexican” (MEAM) series of historical figures and contemporary pop personalities painted brown; and extended series, “The Brown Dot Project” of transformations of Latino populations and workforce data into engaging visual representations using brown dots. MEAM sculptures, handmade books and manipulated aluminum sublimation prints began in 2011 when the artist worked out her own query, “I’m a person of the world. What would the world of contemporary images look like from my own personal Mexican-American, Chicano lens?” From the Three Stooges to Jennifer Lawrence to the Statue of Liberty, these iconic works in brown and titled in Spanish, presented in striking fashion, challenge audiences, “Does color and class define our understanding and appreciation of our culture?” “The Brown Dot” series are dotted objects and abstract images on graphed pages with statistics built into the pointillated designs, stats as the titles, such as National Latino Authors and Writers 5.6% dotted to create a typewriter; or National Latino Architects 7.2% into a VW Beetle. The series has traveled in solo and group exhibitions for a few years now, but its relevancy endures.

ANNE BRIGMAN: A VISIONARY IN MODERN PHOTOGRAPHY

September 29, 2018 – January 27, 2019

Nevada Museum of Art, Reno

Not enough can be said about the innovative, ethereal and intimate photography of Anne Brigman, though this exhibition, the largest ever undertaken including over 300 works spanning her career, attempts to honor her amazing radical oeuvre. Objectifying her own nude body outside in near desolate wilderness was absolutely revolutionary at the turn of the twentieth century, moreover her well-known landscape photography, poetry and art criticism maintained for her a significant career. Her sinuous figure aligns naturally with the lines of the trees and landscapes of Sierra Nevada. Her powerful poses wreak vulnerability and strength, echoing Francesca Woodman decades after her, but with an inner confidence and strength. Brigman redefined the space through her work as did Judy Chicago, Brigman a feminist artist before the notion.

Leonor Fini: Theatre of Desire, 1930-1990

September 28, 2018 – March 4, 2019

Museum of Sex, New York

With an unapologetic dose of theatricality appropriate for its subject, this small but comprehensive survey curated by Lissa Rivera offers a delectable opportunity to discover, re-evaluate and celebrate the art and life of Leonor Fini as well as the rebellious inextricability of both.

Born in Buenos Aires, but raised in Trieste—only by her mother upon her separation of her abusive father whom she escaped by often dressing like a boy—Fini begun to paint at the age of thirteen and by the time she moved to Paris in 1931 had already established herself “as an artist to watch.” While best remembered today as a Surrealist due to her early style, affiliations and her participation in the seminal 1936 MoMA show, Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism, and her illustrations of Marquis de Sade Juliette, Fini refused membership in any of the contemporary avant-garde movements and pursued a fiercely independent course in life and art, marked by her eccentric disguises, life-long partnership with two men, and a radical exploration of desire, sexuality, and performativity that cuts across all the media she worked as painter, idiosyncratic draughtsman, and prolific theater designer. Spanning two floors and six decades of work, the exhibition brings together fascinating examples of the changing style of this largely self-taught artist’s painting (presided over by her 1940s androgynous male nudes guarded by female lovers), erotic drawings, book illustrations, and samples her work in theater and design, contextualizing her production and theatrically fleshing out her performative person with photographic and filmic documentation, signature outfits, a projected assortment of select quotes by the artist, and music.

While arrayed along chronological lines, the exhibits are curated in eloquent and eloquently analyzed groupings that capture Fini’s feminism both as an advocate of the feminine and female desire as well as an explorer of a radically boundlessness sexuality. “Subverting the Muse,” “Empowering the Feminine,” “Metamorphosis and Sexual Sorcery,” “Intellectual Explorations of Sexuality,” and “The Corporeal” are a few of such groupings’ titles that speak volumes of both the timeliness of Fini’s sexual politics and the earliness of her revolt, and are convincingly illustrated by her representations of both men and women, her empowering evocation of sorcery, mythology and nature, her work’s unrestricted erotics, ranging from androgynous objects of female desire to homoeroticism and Sadean sadomasochism, and the fluidity of gender and sexuality emanating from her images, disguises, and words.

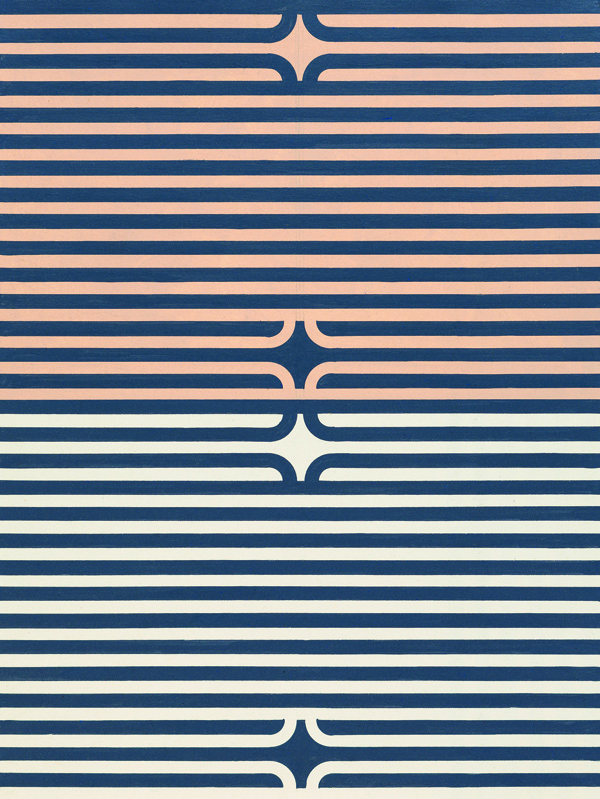

Bridget Riley

November 16, 2018 – January 26, 2019

Sprüth Magers, Los Angeles

“The curve is a frozen moment,” said Bridget Riley in an interview with The Telegraph, “This side contracts. That side extends. When we see a painted curve we somehow recognize that.” This gathering of work from across Riley’s rigorous and focused career gives a viewer an opportunity to test that observation. From Riley’s early experiments with pointillism, Pink Landscape (1960), to her recent paintings and wall murals consisting of subtly-modulated, colored discs, this show is arranged by “conceptual and compositional affinity rather than chronology.” Seen in this way, what emerges is a set of related concerns—the stripe, for instance—which can then be traced across the artist’s career. More than a survey-text example of Op Art, Riley’s work asks for the perceptual and bodily investment of the viewer; a recognition, a frozen moment, a curve, a line.

News from the Art and Academic Worlds

posted by CAA — Nov 28, 2018

Want articles like these in your inbox? Sign up: collegeart.org/newsletter

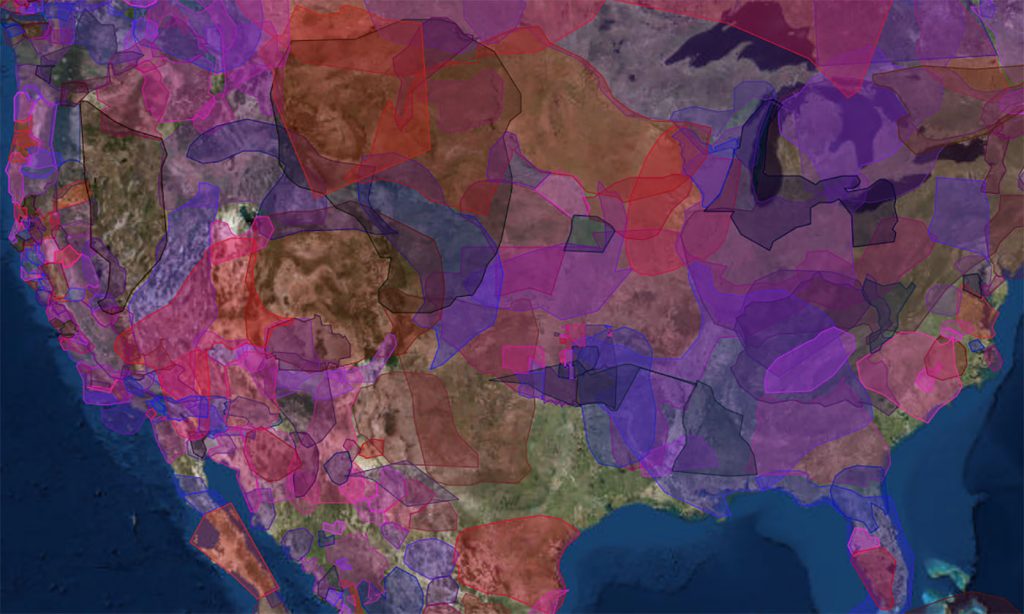

Native Land is a free online tool that seeks to map Indigenous languages, treaties, and territories. Image: Yes Magazine

‘Management Should Be Ashamed’: MoMA PS1 Installers and Maintenance Workers’ Union Protests Pay Rates

The union says the rates its members are paid are below the industry standard. (ARTnews)

This App Can Tell You the Indigenous History of the Land You Live On

Native Land is a free online tool that seeks to map Indigenous languages, treaties, and territories. (Yes Magazine)

Barbara Kruger Revisits a 40-Year-Old Series That’s as Relevant as Ever

The show is an invitation to reflect on what’s changed—and what hasn’t—across American politics since 1978. (Artsy)

Bauhaus Histories Tend to Be Disproportionately Dominated by Male Protagonists

The role of female Bauhauslers in shaping the course of modern design is at last being addressed. (Dezeen)

How Mexican and Chicanx Activism Flourished in 20th-Century Los Angeles

Political art-making and organizing have continued unabated for over a century in Los Angeles, starting with an influential newspaper by two anarchist Mexican brothers. (Hyperallergic)

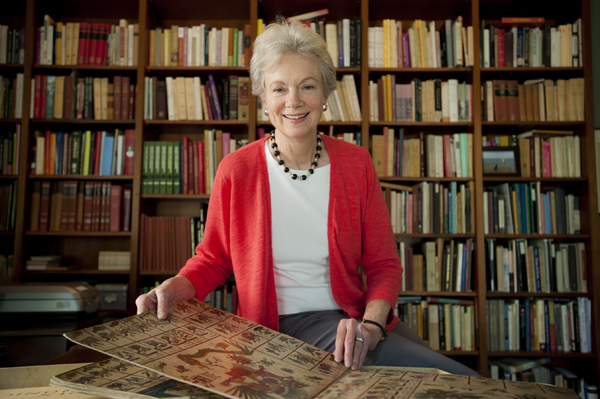

An Interview with Elizabeth Hill Boone, 2019 CAA Distinguished Scholar

posted by CAA — Nov 20, 2018

We are pleased to welcome Elizabeth Hill Boone, Professor of History of Art and Martha and Donald Robertson Chair in Latin American Art at Tulane University, as the 2019 CAA Distinguished Scholar.

An expert in the Precolumbian and early colonial art of Latin America with an emphasis on Mexico, Professor Boone is the former Director of Pre-Columbian Studies at Dumbarton Oaks and recipient of numerous honors and fellowships, including the Order of the Aztec Eagle, awarded by the Mexican government in 1990.

CAA media and content manager Joelle Te Paske corresponded with her recently to learn her thoughts on art history, scholarship, and challenges in the field. Read their interview below.

Photo: Paula Burch, Tulane University

Joelle Te Paske: Thanks for taking the time to speak with CAA. So, where are you from originally?

Elizabeth Hill Boone: Coming from a military family rooted in Virginia, I moved from coast to coast often as a child and then attended the College of William and Mary in Virginia for my BA.

JTP: What pathways led you to the work you do now?

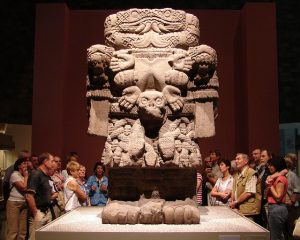

EHB: It was at William and Mary, where I was a Fine Arts major. The sculpture professor Carl Roseberg offered a course, Ancient Art, that included a three-week section on the Pre-Columbian Americas. He showed us and presented the then-canonical explanation of the monumental “Coatlicue” sculpture from Aztec Mexico, and I was immensely intrigued. I wondered what kind of mind would conceptualize and carve a work like that as its creator or mother goddess. That question led me into Aztec studies, which took me to the University of Texas at Austin for my PhD, and to Aztec painted books, where similar images were to be found. I became a manuscript specialist because I needed to understand what the manuscript paintings meant, how they related to the Coatlicue, why they came to fill those particular pages. Since the field of Mexican manuscript painting was in its infancy, I left the Coatlicue behind to focus on the other manuscript genres and Mexican pictography as a system. My study of Mexican pictography naturally led me to the issue of how the concept of Writing should be broadened.

JTP: What are you working on currently?

EHB: I am now finishing up a book analyzing the corpus of pictorial manuscripts created in the early colonial period to document the ideologies and practices of Aztec culture. United by their decendency from Mexican pictography, these painted reflections of the Aztec past were re-purposed to inform Europeans principally about Aztec religion, as weapons of conversion and aids for colonial administrators.

JTP: What is your favorite part of the work you do?

EHB: I think most art historians love solving mysteries: discovering connections and uncovering histories and contexts. I want to understand what an object meant to its different audiences at the time of its creation, and also what it can tell us now about our own perspectives. Depending on the object, it can also be rewarding and telling to track its reception and reconceptualization through time.

Coatlicue Statue in National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City. Photo: Antony Stanley

JTP: If you could boil your teaching philosophy down to a central idea, what would it be?

EHB: My goal is to excite students about the potentials of visual expression. This means giving them knowledge of the material such that they can understand its cultural context and power, but also showing the students how the objects speak today as works of art.

JTP: What’s exciting to you right now in the field?

EHB: Globalism. The discipline has broken the confines that once centered it in Western Europe and is now focusing on connections between peoples. Centers of discourse are now shifting toward the larger Atlantic world, the Pacific world, the Silk Road, and the trans-Mediterranean/African network, to name just a few. It is opening up new ways of understanding the meaning and agency of art.

JTP: What do you see as the greatest challenges in the field right now?

EHB: I see two challenges. The first and most important is relevance. Art history must articulate why it matters in these times. As graphic communication (communication that is not oral or gestural) becomes even more the principal form of communication between people, the discipline needs to assert its place as a source of theoretical knowledge and of models for investigative practice.

The second challenge is linked to the increasing study of trans-cultural connections. Scholars who seek to follow the movement of objects and ideas across spaces and between cultures need to develop strong local knowledge of all participants, so that these global connections are grounded in area expertise. In order to avoid facile comparisons and connections, researchers now have to master multiple areas.

JTP: Have you attended CAA conferences? Do you have a favorite memory?

EHB: I have attended many. Perhaps my favorite memories are of cross-cultural sessions that focus on issues relevant to many cultures, for example, civic identity, and in which the presenters push their material to address the large question in a serious way.

JTP: Thank you, Professor Boone. We’re looking forward to seeing you at the 2019 conference.

Elizabeth Hill Boone is Professor of History of Art and Martha and Donald Robertson Chair in Latin American Art at Tulane University. An expert in the Precolumbian and early colonial art of Latin America with an emphasis on Mexico, she is the former Director of Pre-Columbian Studies at Dumbarton Oaks. Professor Boone has earned numerous honors and fellowships, including the Order of the Aztec Eagle, awarded by the Mexican government in 1990. She is a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and a Corresponding Member of the Academia Mexicana de la Historia. Her research interests range from the history of collecting to systems of writing and notation, and are grounded geographically in Aztec Mexico, but extend temporally for at least a century after the Spanish invasion. She is the author of Cycles of Time and Meaning in the Mexican Books of Fate (Texas, 2007) and Stories in Red and Black: Pictorial Histories of the Aztecs and Mixtecs (Texas, 2000), which was awarded the Arvey Prize by the Association for Latin American Art.

CAA Announces 2019 CAA-Getty International Program Participants

posted by CAA — Nov 02, 2018

CAA is pleased to announce this year’s participants in the CAA-Getty International Program. Now in its eighth year, this international program supported by the Getty Foundation will bring fifteen new participants and five alumni to the 2019 Annual Conference in New York City. The participants—professors of art history, curators, and artists who teach art history—hail from countries throughout the world, expanding CAA’s growing international membership and contributing to an increasingly diverse community of scholars and ideas. Selected by a jury of CAA members from a highly competitive group of applicants, participants will receive funding for travel expenses, hotel accommodations, conference registration, CAA membership, and per diems for out-of-pocket expenditures.

At a one-day preconference colloquium, to be held this year at Parsons School of Design, the fifteen new participants will discuss key issues in the international study of art history together with five CAA-Getty alumni and several CAA members from the United States, who also will serve as hosts throughout the conference. The preconference program will delve deeper into subjects discussed during last year’s program, including such topics as postcolonial and Eurocentric legacies, interdisciplinary and transnational methodologies, and the intersection of politics and art history.

This is the second year that the program includes five alumni, who provide an intellectual link between previous convenings of the international program and this year’s events. They also serve as liaisons between CAA and the growing community of CAA-Getty alumni. In addition to serving as moderators for the preconference colloquium, the five alumni will present a new Global Conversation during the 2019 conference titled Creative Pedagogy: Mapping In-between Spaces Across Cultures.

The goal of the CAA-Getty International Program is to increase international participation in the organization’s activities, thereby expanding international networks and the exchange of ideas both during and after the conference. CAA currently includes members from over 50 countries around the world. We look forward to welcoming the following participants at the next Annual Conference in New York City.

2019 PARTICIPANTS IN THE CAA-GETTY INTERNATIONAL PROGRAM

Richard Bullen is associate professor of art history at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand. He graduated with a PhD from the University of Otago in 2003. Bullen’s principal areas of research are Japanese aesthetics and East Asian art collections in New Zealand. During his years living in Japan, he studied tea ceremony and calligraphy and has since published on aspects of tea ceremony aesthetics. With James Beattie he recently completed a major publicly-funded project to document New Zealand’s largest collection of Chinese art, the Rewi Alley Collection at Canterbury Museum. Their website catalogues all 1400 objects in the collection: http://www.rewialleyart.nz. Together, they also have produced a number of publications, including New China Eyewitness: Roger Duff, Rewi Alley and the Art of Museum Diplomacy (2017) and co-curated three exhibitions. Bullen is currently working on art made in World War II by Japanese POWs held in Australasia.

Pedith Chan is an assistant professor of Cultural Management in the Faculty of Arts at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. She received her PhD in Art and Archaeology from SOAS, University of London. Before joining the Chinese University of Hong Kong Chan was an assistant curator at the Hong Kong Museum of Art, and an assistant professor at the City University of Hong Kong. Her research interests focus on the production and consumption of art and cultural heritage in modern and contemporary China. Recent publications include The Making of a Modern Art World: Institutionalization and Legitimization of Guohua in Republican Shanghai (Leiden: Brill, 2017), “Representation of Chinese Civilization: Exhibiting Chinese Art in Republican China,” in The Future of Museum and Gallery Design (London: Routledge, 2018), and “In Search of the Southeast: Tourism, Nationalism, Scenic Landscape in Republican China,” (Twentieth-Century China, 2018). She is currently researching the making of scenic sites in modern China.

Swati Chemburkar is an architectural historian who lectures and directs a diploma course on Southeast Asian Art and Architecture at Jnanapravaha, a center for the arts in Mumbai, India. In addition, she is a visiting lecturer at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), London, and SOAS’s summer schools in Southeast Asian countries. Chemburkar’s work focuses on eighth- through twelfth-century Southeast Asia, particularly the relationship between texts, rituals, art, architecture, and cross-cultural exchanges in maritime Asia. Her ongoing research explores the spread of the ancient Śaiva sect of Pāśupatas in this region. She has edited Art of Cambodia: Interactions with India (Marg Magazine, Volume 67 Number 2, December 2015-March 2016) and contributed papers to several journals and publications, including the recent “Visualising the Buddhist Mandala: Kesariya, Borobudur and Tabo” in India and Southeast Asia: Cultural Discourse (K. R. Cama Oriental Institute, Mumbai, 2017) and “Pāśupata Sect in Ancient Cambodia and Champa” (co-authored with Shivani Kapoor) in Vibrancy in Stone: Masterpieces of the Đà Nẵng Museum of Cham Sculpture (River Books, 2017).

Stephen Fọlárànmí is a senior lecturer in the Department of Fine & Applied Arts, Ọbáfémi Awólọ́wọ̀ University, Ilé-Ifè, Nigeria. His research focuses on Yoruba art and African mural art and architecture. In particular, Fọlárànmí’s extensive research on the art and architecture of the Òyó and Iléṣà palaces has been published in journals, conference proceedings, and as book chapters. A recent example, “Palace Courtyards in Iléṣà: A Melting Point ofTraditional Yorùbá Architecture,” co-authored with Adémúlẹ̀yá, B.A., was published in Yoruba Studies Review 2, no. 2 (Spring 2018): 51-76. Fọlárànmí was a recipient of the first Höffmann-Dozentur für Interkulturelle Kompetenz at University of Vechta, Germany (2008-09). As an artist Fọlárànmí has exhibited his work in Nigeria, London, Germany, and the United States. He was the chair of the Department of Fine and Applied Arts, Obafemi Awólọ́wọ̀ University, Ile-Ife, between August 2016 and January 2018. Currently, he is a research fellow in the Fine Arts Department, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa.

Negar Habibi is a Persian art historian and lecturer in Islamic art history at the University of Geneva, Switzerland, where she teaches history of Persian painting from early Islamic times until the modern era. She completed a PhD in 2014 in art history at the Aix-Marseille University in France with a dissertation titled “The Farangi sāzi and Paintings of Ali Qoli Jebādār: an Artistic Syncretism under Shah Soleymān (1666-1694).” Habibi conducts research on paintings from early modern Iran. Adopting a multidisciplinary approach, her work focuses on the career and life of the artist, especially issues of signature authenticity, gender, and artistic patronage in early modern Iranian society. She has published several articles on the art and artists of late-seventeenth-century Iran, and her book titled Ali Qoli Jebādār et l’occidentalisme safavide: une étude sur les peintures dites farangi sāzi, leurs milieux et commanditaires sous Shah Soleimān (1666-94) was published in January 2018 by Brill.

Iro Katsaridou has been the curator of modern and contemporary art at the Museum of Byzantine Culture in Thessaloniki, Greece since 2005. She studied art history at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and the Université Paris I-Sorbonne, and also pursued museum studies at the City University of New York. Her doctoral dissertation (Aristotle University, 2010) focused on contemporary Greek photography from 1970-2000. For the past five years Katsaridou has been researching historical photography in Greece, seeking to unravel the role of politics in the formation of photographic representations. In this particular field she also has curated exhibitions of photography and art in wartime (World War I and II) and edited related catalogues. She has co-edited a book about photography during the Nazi Occupation of Greece (1941-1944) and written articles and book chapters on photography (both historical and contemporary), exhibition display policies, as well as the relationship between contemporary Greek art and politics.

Halyna Kohut is an associate professor in the Faculty of Culture and Arts at the Ivan Franko National University of Lviv, Ukraine, where she teaches history of art, contemporary art, and history of theatrical costume. Originally educated as a textile artist, she received a PhD from the Lviv National Academy of Arts with a dissertation on seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Ukrainian kilims. She is the recipient of scholarships and grants from the Austrian Agency for International Mobility and Cooperation in Education, Science and Research, the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Alberta, and the Queen Jadwiga Foundation at the Jagiellonian University in Cracow. Kohut studies Ukrainian kilims as an intermediate zone between Oriental and Western design traditions formed on the so-called Great cultural frontier between the Christian West and Islamic East. She is especially interested in the migration of ornamental patterns as well as the articulation of textile’s social and political meanings in the historical context.

Zamansele Nsele is an art historian and a lecturer in design studies in the Faculty of Art, Design and Architecture at the University of Johannesburg, South Africa. She recently submitted her doctoral thesis in Art History & Visual Culture, titled Post-Apartheid Nostalgia and the Future of the Black Visual Archive. In 2018, Nsele was included in the Mail & Guardian’s prestigious list of Top 200 Young South Africans. She has presented her PhD research at Vanderbilt University and Rutgers University (USA), the University of East Anglia (UK), the University of Ghana in Accra (Ghana), and Rhodes University and the University of Cape Town (South Africa). In July 2018, she was a guest speaker at the Museum Conversations Conference hosted by the University of Namibia and the Goethe-Institut Namibia. Her research interests include post-Apartheid nostalgias, contemporary African art, blackface minstrelsy in South African visual culture and Africana studies.

Chukwuemeka Nwigwe is a Nigerian artist and art historian who teaches fashion/textile design and art history at the University of Nigeria Nsukka. He holds a PhD in art history, MFA in textile design, and BA in fine and applied arts from the same university. Nwigwe’s current research is on identity, exemplified in two recent publications: “Fashioning Terror: The Boko Haram Dress Code and the Politics of Identity” (Journal of Fashion Theory, January 2018) and “Breaking the Code: Interrogating Female Cross Dressing in Southeastern Nigeria” (posted online as part of a 2018 ACLS African Humanities Program Postdoctoral Fellowship). Nwigwe also practices as a studio artist. His recent studio experiments with waste plastic, synthetic bags, and foil wrappers, usually woven arbitrarily, have been influenced largely by his research on bird nests begun during his MFA studies.

Oana Maria Nicuță Nae is an assistant professor in the Department of Art History and Theory, Faculty of Visual Arts and Design, George Enescu National University of Arts, Iasi, Romania. She received a PhD in art history from the same university, where she currently teaches courses on the history of modern European art, the history of design, and art and society in modern Europe. Most recently she published “The Materialization of Light in the Art of the (Neo-) Avant-Gardes,” in Objects and Their Traces: Historical Gazes, Anthropological Narratives, Cristina Bogdan, Silvia Marin Barutcieff (coord.), Bucharest University Press (Bucharest, 2018). Nicuță Nae’s current research focuses on the representation of women in Romanian modern art. She also studies multiple modernities, taking into account the particular position of Romanian art narratives in regional and global attempts to construct encompassing ones. Recently she has started parallel research on the notion of influence in nineteenth-century Romanian and European art.

Tamara Quírico is an associate professor in the Art Institute of the Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (State University of Rio de Janeiro, UERJ, Brazil), where she teaches courses to undergraduate students majoring in art history and visual arts and art history courses to graduate students pursuing MA and PhD degrees. She earned her PhD in social history from the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, in a joint supervision program with the Università di Pisa (Italy), in which she studied changes in the iconography of the Last Judgment in fourteenth-century Tuscan painting. Her dissertation, “Inferno and Paradiso: Representations of the Last Judgment in Fourteenth-Century Tuscan Painting,” was published in Portuguese in 2014. Quírico studies Italian paintings from the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries, focusing in particular on the uses and functions of Christian images, as well as devotional practices and exchanges between Christian images from Europe and Spanish America.

Juliana Ribeiro da Silva Bevilacqua is a specialist in African and Afro-Brazilian art. She studied at the University of São Paulo, where her PhD dissertation was on the Museu do Dundo in Angola (1936–61). From 2004–14 she worked as a researcher at the Museu Afro Brasil in São Paulo. She collaborates with different museums in Brazil researching African art and Afro-Brazilian art collections, including the Museu de Arte de São Paulo and the Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia at the University of São Paulo. In 2015 she was a guest editor of Critical Interventions: Journal of African Art History and Visual Culture in an issue dedicated to Afro-Brazilian Art. Since 2017 she has been a professor collaborating with the graduate program in Art History at the University of Campinas (Unicamp). Recently she was a visiting professor at the Universidad de Los Andes, Bogota, Colombia, in the Connecting Art Histories program sponsored by the Getty Foundation.

Marko Stamenkovic, born in the former Yugoslavia, is an associate curator of ZETA Contemporary Art Center in Tirana, Albania. He is an art historian and transcultural theorist with a strong interest in the decolonial politics of race, ethnicity, and sexuality. Over the past decade, he has been working primarily in the field of contemporary visual arts as a freelance curator, critic, and writer focused on the intersection of visual thinking and social theories, political philosophies, and cultural practices of the marginalized and the oppressed. He holds a PhD in philosophy from Ghent University (Belgium) where he worked on questions of sacrifice, self-sacrifice in protest, and suicide to explore the relationship between human mortality and politico-economic powers on the darker side of democracy, from a perspective of the global South. He is a member of AICA (International Association of Art Critics) and IKT (International Association of Curators of Contemporary Art).

Viviana Usubiaga holds a PhD in art history from the Universidad de Buenos Aires (UBA) in Argentina. She is an associate professor of contemporary art at the Universidad Nacional de San Martín and an assistant professor of modern and contemporary art history at UBA. Usubiaga is also an adjunct researcher of the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET) and a board member of the Centro Argentino de Investigadores de Arte (CAIA). Her fields of interest include visual arts, literature, and museum studies, focusing on the political impact of transnational circulation of artistic images and texts during socially traumatic periods, including dictatorships and post-dictatorships in South America. Being a specialist in resistance art practices and institutional cultural politics, Usubiaga is the author of Imágenes inestables. Artes visuales, dictadura y democracia en Buenos Aires (2012). She also organizes independent curatorial projects in which she experiments with using scholarly methodologies in non-academic or non-specialist settings.

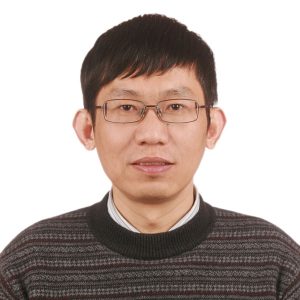

Jian Zhang was born in Hangzhou, China, and earned his PhD in art theory and history from the China Academy of Art, Hangzhou. He is a professor of art history at the School of Art and Humanities as well as the chief librarian of the Academy Library at the same university. His present research focuses on expressionism (formalism) in modern art historiography as well as the problem of its modernity. He is the author of Life of the Visual Form of Art, The History of the Western Modern Art, and An Alternative Story: Expressionism in the Western Modern Art Historiography, and also the translator of the Chinese edition of Wilhelm Worringer’s Form in Gothic, Heinrich Wolfflin’s The Sense of Form in Art: A Comparative Psychological Study (Italien und das deutsche Formgefühl) and Conrad Fiedler’s On Judging Works of Visual Art.

PARTICIPATING ALUMNI

Sarena Abdullah is a senior lecturer in the School of the Arts at the Universiti Sains Malaysia in Penang, where she teaches art history to undergraduate and graduate students. She received an MA in art history from the University at Buffalo, State University of New York, and a PhD in art history from the University of Sydney in Australia. Specializing in contemporary Malaysian art with a broader interest in Southeast Asian art, Abdullah was the inaugural recipient of the London, Asia Research award given by Paul Mellon Center (London) and Asia Art Archive (Hong Kong). Her book Malaysian Art since the 1990s: Postmodern Situation was published in 2018, as was Ambitious Alignments: New Histories of Southeast Asian Art, for which she was a co-editor, published by the Power Institute and National Gallery Singapore. She first participated in the CAA-Getty International Program in 2016 and presented a paper as part of the program’s reunion during the 2017 conference.

Katarzyna Cytlak is a Polish art historian based in Buenos Aires, Argentina, whose research focuses on Central European and Latin American artistic creations in the second half of the twentieth century. She studies conceptual art, radical and utopian architecture, socially engaged art, and art theory in relation to post-socialist countries from a transmodern and transnational perspective. In 2012, she received a PhD from the University Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, France. Cytlak was a postdoctoral fellow at the CONICET – National Scientific and Technical Research Council, Argentina (2015-2017). She is currently working as a researcher and professor at the Center for Slavic and Chinese Studies, University of San Martín, Argentina. Selected publications include articles in Umění/Art, Eadem Utraque Europa, Third Text, and the RIHA Journal. Cytlak is a grantee of the University Paris 4 Sorbonne (Paris), the Terra Foundation for American Art (Chicago, Paris) and the Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art (INHA, Paris). In 2018, she participated in the CAA-Getty International Program.

Nadhra Khan is a specialist in the history of art and architecture of the Punjab from the sixteenth to the early twentieth century. She received a PhD from the University College of Art & Design, University of the Punjab, Lahore, and teaches art history at Lahore University of Management Sciences, Lahore, Pakistan. Khan’s research focuses on the visual and material culture of the Punjab region during the Mughal, Sikh, and colonial periods. Her publications address several misconceptions and misrepresentations of Mughal and Sikh art and architecture as well as the state of art and craft in the Punjab under the British Raj and reflect the wide range of her interests and expertise.

Nazar Kozak is a senior research scholar in the Department of Art Studies in the Ethnology Institute at the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. Previously he also taught the history of art at the Ivan Franko National University of Lviv. Kozak has received scholarships and grants from the Fulbright Scholar Program, State Scholarships Foundation of Greece, the American Council of Learned Societies, the Austrian Agency for International Mobility, and the Shevchenko Scientific Society in the United States. Kozak’s primary research is on Byzantine and post-Byzantine art in Eastern Europe. He is the author of Obraz i vlada: Kniazhi portrety u mystetstvi Kyïvskoï Rusi XI stolittia (Image and authority: Royal portraits in the art of Kyivan Rus’ of the eleventh century, Lviv, 2007). More recently, he has begun to work on contemporary activist art. His article on the art interventions during the Ukrainian Maidan revolution was published in the Spring 2017 issue of the Art Journal; it received an honorable mention as a finalist for that year’s Art Journal Award. Kozak participated in the CAA-Getty International Program in 2015 and presented a paper as part of the program’s reunion during the 2017 conference.

Chen Liu teaches art history and architecture at Tsinghua University in Beijing, China, where she received a bachelor’s degree in architecture with honors. After receiving a master’s in architecture and urban planning from the University of Maryland in 2000, she practiced as an architect in Washington DC until 2005. In 2011, she received a PhD in art history from Princeton University, specializing in Renaissance and Baroque art and architecture. In 2012, funded by an Andrew W. Mellow Fellowship, she helped create and direct the first Villa I Tatti summer research seminar designed specifically for Chinese scholars. “The Unity of the Arts in Renaissance Italy” provided participants with the opportunity to study firsthand the art and architecture of Renaissance Italy. Liu also teaches courses on the visual arts at Beijing Film Academy and Tongji University (Shanghai). She publishes widely on early modern art and architecture, as well as on the response of Chinese scholars to the Italian Renaissance. For the academic year 2018-2019 Liu is a Harvard-Yenching Institute Visiting Scholar at Harvard University.

New in caa.reviews

posted by CAA — Oct 26, 2018

Joanne Allen reviews The Medieval Salento: Art and Identity in Southern Italy by Linda Safran. Read the full review at caa.reviews.

Blake Stimson writes about Revoliutsiia! Demonstratsiia! Soviet Art Put to the Test, edited by Matthew S. Witkovsky and Devin Fore. Read the full review at caa.reviews.

Shira Brisman discusses Animating Empire: Automata, the Holy Roman Empire, and the Early Modern World by Jessica Keating. Read the full review at caa.reviews.

Rebecca Corbett explores Around Chigusa: Tea and the Arts of Sixteenth-Century Japan, edited by Dora C. Y. Ching, Louise Allison Cort, and Andrew M. Watsky. Read the full review at caa.reviews.

Nicholas Miller writes about Archibald Motley Jr. and Racial Reinvention: The Old Negro in New Negro Art by Phoebe Wolfskill. Read the full review at caa.reviews.

International Review: L’Algérie de Gustave Guillaumet by Roger Benjamin

posted by CAA — Oct 26, 2018

The following article was written in response to a call for submissions by CAA’s International Committee. It is by Roger Benjamin, professor of art history, University of Sydney, Australia.

Exhibition review: L’Algérie de Gustave Guillaumet (1840-1887), Musée des Beaux-Arts de La Rochelle (France), June 8-September 17, 2018

In a most unassuming regional museum in France, an exhibition of real art-historical significance opened this past June. For the first time since 1899, the work of the preeminent French Orientalist painter of the later 19th century has been brought together. Gustave Guillaumet is not an obscure artist, as every survey of Orientalism since the great Royal Academy show of 1984 has included his paintings. But the scholarly work had not been done until now, when the fruits of Marie Gautheron’s 2015 doctoral dissertation on the desert and Guillaumet have been brought to bear (Gautheron, M., L’invention du désert: émergence d’un paysage, du début du XIXe siècle au premier atelier algérien de Gustave Guillaumet (1863-1869), Paris Nanterre University).

Fig. 1. Gustave Guillaumet, La Famine en Algérie, Salon of 1869, oil on canvas, 122 x 92 in (309 x 234 cm) Le Musée National Public Cirta de Constantine, Algeria (restored for the exhibition).

Many of the works on view in La Rochelle are unfamiliar, coming from regional museums, the artist’s descendants, private enthusiasts, and storage collections of the Musée d’Orsay. The largest single work was thought to have been lost. The Famine in Algeria (Fig. 1), the most disturbing large scale canvas at the Salon of 1869, was known only by a poor woodcut and several drawings. Its subject was altogether too tough—the cadaverous members of two Arab families expiring on the pavement of a city in what was (in French law) a department of France, the province of Algiers in Algeria.

La Famine had been languishing, rolled up and torn in the basement of the National Public Museum of Constantine, Algeria (Le Musée National Public Cirta de Constantine). The research of Dr. Gautheron located it, and through the goodwill of Algerian curators and the political weight of Maître Salim Becha (an Algiers-based lawyer, art collector and philanthropist) the work was sent to France for restoration. A successful crowd-funding campaign led by Annick Notter, chief curator at La Rochelle, paid for the conservator Pascale Brenelli, who spent nine hours every day from early February until mid-June resurrecting the picture.

Guillaumet’s ghastly image of a baby suckling at the collapsed breast of its dead mother goes back through Eugène Delacroix to Nicolas Poussin and classical precedents. Entirely new, however, is his angular figure of an emaciated Arab father who, supporting his fainting teenage son, reaches up for a loaf of bread being handed down from the tiny window of a prosperous home. The outstretched hand is female, bejeweled and, through the curvature of its fingers, evocative of the Jewish beauties painted by Chasseriau in Constantine (1846) and by Delacroix in Tangier (1832).

La Famine’s grisly treatment was probably influenced by photographs of the dying taken in situ. Catalogue author (and leading historian) Jacques Frémaux estimates one third of the indigenous population of Algeria died in the famine of 1866-70, due to drought, locust plague, cholera, and the expropriation of farmlands by European settlers. La famine is unrelieved by aesthetic ‘sweet spots’ like the majestic horseman that Delacroix placed in his Massacres of Chios. We have instead the moral and visual austerity that pervades Guillaumet’s work. A grave witness to these events, Guillaumet was not about to beautify them.

Fig. 2. Gustave Guillaumet, La Séguia, près de Biskra, oil on canvas, 1884, Salon of 1885, 39 x 61 in (100 x 155.5 cm), Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

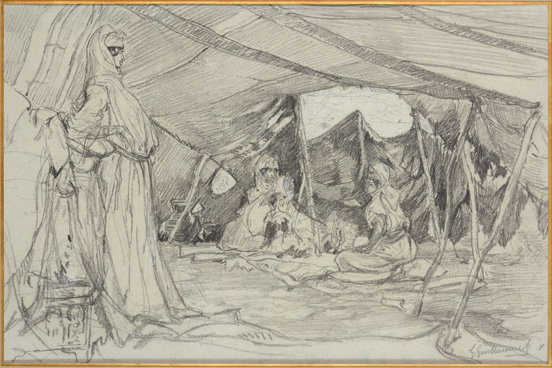

Almost all of the artist’s best-known landscapes are on view, including The Sahara of 1867, with its camel skeleton and mirage at the horizon with a setting sun, and the dazzling Séguia, Biskra (Fig. 2) of 1884. (Both are usually on display at the Musée d’Orsay). The loan of numerous restored pencil drawings and watercolors from the Orsay was intended to show the genetic relationship between such studies and the resultant tableaux by Guillaumet (who narrowly missed the Prix de Rome for landscape and ended up heading to Algiers in 1862 rather than Rome). (Fig. 3)

It came as a shock to learn that many of these drawings could not be exhibited on the second floor of the eighteenth-century mansion that houses the Musée de la Rochelle, as it was condemned by city architects one week before the scheduled opening. Despite the best efforts of the staff, this major exhibition was opened in almost third world conditions: a building with the floor above held up by a dozen massive steel columns, no air conditioning, and inadequate spotlighting. Yet historic La Rochelle is a wealthy city, with a new 5,000-boat marina and an opulent public library, the Mediathèque, nearby. City and provincial authorities must reward the enterprise of its art curators by providing an adequate home for future temporary exhibitions and permanent collections.

Fig. 3. Gustave Guillaumet, Sous la tente, graphite pencil on paper, 9.5 x 17 in (24 x 44 cm), private collection. Photo: A. Leprince.

Fortunately, L’Algérie de Gustave Guillaumet will travel to two other regional museums in much better condition: the Limoges Fine Arts Museum and the celebrated La Piscine, a converted Art Nouveau baths complex in the northern city of Roubaix. And happily, the catalogue, a scholarly book with first-class production values and superb plates, perfectly represents the project. Its backbone is the set of four chapters by Gautheron, a former academic teaching art history and visual culture at the École normale supérieur de Lyon, along with detailed entries on key works and a documentary apparatus at the end. Gautheron was careful to enlist a range of other writers, including Algerian literary figures like Leïla Sebbar, and art historians from Algeria, the United States, Australia, France, and Ireland. For her part Gautheron has also completed a 300-page monograph on Guillaumet that is awaiting publication.

Fig. 4. Gustave Guillaumet, Habitation saharienne (Cercle de Biskra), Salon of 1882, oil on canvas, 58 x 68 in (146.1 x 173.4 cm), Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Virginia, gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr.

Guillaumet, like the admirable Eugène Fromentin before him, traveled initially in Algeria in close connection with the officers of the French army and its political wing, the Bureau Arabe. His stunning series of interiors of Arab houses, made in the oasis villages of Biskra and Bou-Saâda, were made possible by the intervention of the Commandant’s wife (as the artist narrates in his text “Les intérieurs,” from his book Tableaux Algériens). Crowning the series but absent from the exhibition was the key Guillaumet work in America, Saharan Dwelling (Fig. 4), recently loaned by the Chrysler Museum of Norfolk Virginia to the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris (see the author’s Biskra, Sortilèges d’une oasis, Paris and Algiers, 2016, pp. 90-91). Scenes of women and their daughters working at looms, the first of their kind and highly influential on the next generation, complement Guillaumet’s earlier assemblages of men, camels and horses on the barren plains—at prayer, at market, or on a military bivouac. Guillaumet, an admirer of J. F. Millet, produces high naturalism, except in one key respect: he always excludes the colonizer and his works. Absent are the soldiers in uniform, colonists directing Berber farmworkers, the modern buildings and telegraph wires at Bou-Saâda, the military hospital at Biskra where the painter convalesced in 1862, or the British tourists who by the 1880s were encumbering the desert scene. Guillaumet’s vision is not a “painting of modern life” as exemplified by the traveler Constantin Guys in Istanbul. It is an image of Algeria as it used to be: a country and a people that won the admiration of foreign travelers, intellectuals and officers, even as their invasive actions helped bring about its demise.

Annual Conference Committee Chair Charlene Villaseñor Black on Why You Can’t Miss CAA 2019

posted by CAA — Oct 23, 2018

Charlene Villaseñor Black is Professor of Art History and Chicana/o Studies at UCLA and chair of the Annual Conference Committee for the 2019 Annual Conference in New York, February 13-16, 2019.

As a crucial player in the conference process, we asked Charlene to share her thoughts on the field, being a part of CAA, and what goes into making the conference a reality every year. Listen in or read her thoughts below.

So, chairing the Conference Committee is a huge job. We had a record number of submissions—there was a lot of reading—but it was also very exciting to see where our members are, and what kinds of things people are doing in terms of their artistic practice, what things art historians are thinking of. It was actually very exhilarating to read these submissions.

When I came on, agreed to do this, I had a couple of goals in mind, and the first one for me was diversifying CAA. Really broadening out what kinds of topics we were looking at. I was also interested in pulling in more people who are working on historic time periods. I’m someone who works on colonial, on early modern but I also work in contemporary Chicanx art. So I’m very much interested in seeing how differing fields can speak to each other, and I was also very much interested in studio art, and a little nervous about that because I actually think that dialogue with artists is extremely important for those of us who are historians.

The submissions that we read were very exciting. There are many different themes, a very diverse representation of subject areas. What was interesting to me was that several themes that transcend chronology or geography came out to me. There were a lot of panels on the politics of artistic production. There were a lot of panels looking at migration, immigration, globalism. There were a lot of panels looking at the environment, artistic practice in the environment. Materiality was another very important topic that I saw that’s still very popular.

So I was very attentive to the representation of historical panels for the annual conference. This is actually very important to me, and there were a lot of early modern panels. As someone who works on early modern colonial and contemporary, I really think about why history matters. And in this current political moment, I think we understand why history matters, and why facts matter. And thinking about the current migration crises in the world right now, the roots of those crises are really in the early modern period, during this period of European imperialism. So I actually think this is a moment when we can really speak to each other across time periods, across fields. It’s a really important moment for us to do that.

I hope that the biggest surprise about the conference is its incredible breadth, and the incredible range of interests that our members have, and people are working on in their studio practices, in their scholarship.

My very first CAA was in 1992. I was a graduate student. It was in Chicago, and I very clearly remember going to that first conference. I felt intimidated. I also remember very well, I think it was 1995, San Antonio. I was on the job market, but what I remember is that there were two Latin American panels. There were two colonial panels. They were scheduled at the same time unfortunately, but I remember presenting at that conference.

CAA is the major professional organization that I belong to. I’m also active in Latinx studies, but CAA for me feels like home. I was very fortunate to win one of the CAA Millard Meiss subventions early on for my first book. CAA to me is just fundamental in terms of you go to the conference, you see what everyone’s working on, what does the field look like at this moment? You see lots of old friends. You hopefully meet some new people.

The job market is a challenge right now for young scholars who are just finishing. Because of the fields I work in, I am very fortunate that my students have done really well. They tend to have multiple job offers. I had two people on the market this year, so I’m very grateful for that. I think it’s actually really important to broaden what it is we can teach and what we can talk about. Not just be highly specialized in twenty years of the 16th century, for example. It’s extremely important to have range, to be able to even move out of art history. A number of my students are also working in ethnic studies right now, and they’ve all done beautifully on the job market.

I think it’s also up to us to argue for the importance of what we do. Visual literacy could not be more important than it is at this particular moment. This is the most visual world that has ever existed, so that visual literacy argument is important for us to make, I feel.

So we had a record number of submissions this year, and I read a lot of them. I read hundreds of the submissions, and really allotted a lot of time to doing it, because you want to make sure you give every submission a fair read and a good read. You don’t want to be grouchy or tired when you’re reading someone’s submission. It’s their work. It’s very important. So I read I’m guessing 400 or 500 of the submissions. Yeah. I really wanted to get a sense of where everybody was.

The final decisions are made by a committee, by the Annual Conference Committee, and there were so many submissions this year that we pulled in extra readers. You want to have a very diverse group of readers because our knowledge tends to be very particular. For example, you want to make sure you have people who are in studio art reading studio art proposals. Somebody who understands maybe contemporary may not understand ancient pre-Columbian. So you want to have readers who are literate in a variety of areas able to read and fairly assess the submissions.

I think it’s really important, and I’m speaking as an advisor, as a mentor, as someone who’s also an editor, that I like it when we put our main idea out first or upfront. When we’re talking in a proposal submission, I think it’s important to not kind of unroll your way to the main point. So I think being direct can really help clarify what you’re talking about.

I think to be successful presenting, it is really important that you’re not just reading, looking down, reading your script. That even if you have to rehearse moments of engagement with the audience, that will really enliven the presentation. Take time to look at the images you’re talking about, to point out things in the images. Take time to engage directly with your audience, make eye contact with them. I know when I’m working with students, it’s very important to tell people that you need to do those things, and to rehearse the paper so that you’re not stumbling—you know what you’re going to say before you say it.

I love the opportunity to connect with people that I haven’t seen since the last conference. I love seeing the latest work that’s happening in art history, and I love hearing artists talk about what they’re doing.

Charlene Villaseñor Black, whose research focuses on the art of the Ibero-American world, is Professor of Art History and Chicana/o Studies at UCLA. Winner of the 2016 Gold Shield Faculty Prize and author of the prize-winning and widely-reviewed 2006 book, Creating the Cult of St. Joseph: Art and Gender in the Spanish Empire, she is finishing her second monograph, Transforming Saints: Women, Art, and Conversion in Mexico and Spain, 1521-1800. Her edited book, Chicana/o Art: Tradition and Transformation, was released in February 2015. She is co-editor of a special edition of The Journal of Interdisciplinary History entitled Trade Networks and Materiality: Art in the Age of Global Encounters, 1492-1800, with Dr. Maite Álvarez of the J. Paul Getty Museum; and editor of a forthcoming issue of Aztlán focused on teaching Chicana/o and Latina/o art history. She has held grants from the Getty, ACLS, Fulbright, Mellon, Woodrow Wilson Foundations and the NEH. While much of her research investigates the politics of religious art and global exchange, Villaseñor Black is also actively engaged in the Chicana/o art scene. Her upbringing as a working class, Catholic Chicana/o from Arizona forged her identity as a border-crossing early modernist and inspirational teacher.

Elizabeth Guffey, Matt Ferranto, and Rebecca Mushtare

posted by CAA — Oct 22, 2018

The weekly CAA Conversations Podcast continues the vibrant discussions initiated at our Annual Conference. Listen in each week as educators explore arts and pedagogy, tackling everything from the day-to-day grind to the big, universal questions of the field.

CAA podcasts are now on iTunes. Click here to subscribe.

This week, Elizabeth Guffey, Matt Ferranto, and Rebecca Mushtare discuss “Bringing Access to Design Practice: Teaching Inclusion in the 21st Century.”

Elizabeth Guffey is Professor of Art & Design History, State University of New York at Purchase.

Matt Ferranto is Associate Professor of Design, Westchester Community College.

Rebecca Mushtare is Associate Professor of Graphic Design, State University of New York at Oswego.

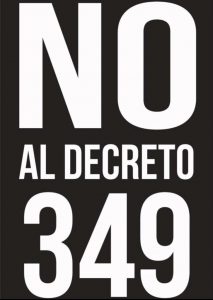

Tania Bruguera on Decree 349, the Criminalization of the Arts in Cuba, and How You Can Help

posted by CAA — Oct 18, 2018

In July 2018, the Cuban government issued Decree 349, legislation targeting the artistic community on the island nation. Under the decree, all artists—including collectives, musicians, and performers—will be prohibited from operating in public or private spaces without prior approval by the Ministry of Culture. It is slated to go into full effect on December 7, 2018.

CAA released a statement of opposition to the decree last month. Recently, CAA media and content manager Joelle Te Paske corresponded with artist, activist, and 2016 CAA keynote speaker Tania Bruguera to learn more.

Tania Bruguera delivers the keynote address at the 2016 CAA Annual Conference in Washington, DC.

Joelle Te Paske: I’ve read that Decree 349 was signed in April and then announced without any consultation on July 10 in the government’s newspaper. How did you first find out about it?

Tania Bruguera: Decree 349 was signed by the new President of Cuba [Miguel Díaz-Canel] without consulting artists—something even the national newspaper had to admit in a recent article, which was ironically published to defend the decree. Also, it was not publicly known until almost six months after it was official, but that didn’t stop them from [moving to] apply it. It was used already with younger artists who participated in the alternative biennial when recording their artist ID registration, the only legal document that protects and allows someone to be an artist in Cuba. They also enforced it with us at the Instituto de artivismo Hannah Arendt (Hannah Arendt Institute of Activism), charging fines of $2,000 for not having permission from the Ministry of Culture to do what they call “artistic services” inside of my house. The last free space we had in Cuba was our homes—now with this law, they are also regulated spaces.

JTP: The decree is wide-ranging and applies to all cultural activity, not just visual art, is that right?

TB: Yes, they are cutting all the heads. There is a strong independent cinema movement, an alternative music scene, DIY theater, and new independent art galleries—they are all going to be gone. The government is presenting this decree as an innocent regulation, but it is in fact a muzzle to artists. We know that those permissions are not based on anything but ideological considerations, and it will be used as a blackmailing instrument. Also, it gives the government the right to decide who is and who is not an artist, what is and what is not art.

JTP: Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, Amaury Pacheco, Iris Ruiz, Soandry Del Rio, and José Ernesto Alonso—artists who organized a protest performance on July 21—were arrested by Cuban police officials and charged with public disorder. Are tactics like this being used to intimidate artists who are speaking out?

TB: When you are protesting, when you get detained, you have already overcome your fears. In my experience, those repressive acts from the government consolidate your ideas. Confronting injustice unifies the group and makes people even more committed to fight. These detentions are designed to discourage by suggesting that your actions won’t change anything. They try to back you away from doing bigger collective demonstrations. Their absurd repression and disproportionate reaction to any small action shows how they are proving themselves wrong. But the real goal of all these engineered scare tactics is to intimidate those who are not protesting.

JTP: The decree specifically targets independent artists working without larger financial support structures. How do you think this will affect cultural life in Cuba?

TB: It is not a matter of finances at least for now—[the government] may use the same tactic of fake tax evasion charges that the Chinese government has used later on. Decree 349 also affects independent cinema which, comparatively, works with a larger budget. It is a matter of stopping artists from imagining, producing, and showing art independently. It is about the Ministry of Culture looking obsolete because it cannot control its artists, and so the law is intervening.

JTP: Amnesty International has written: “The lack of precision in the wording of the decree opens the door for its arbitrary application to further crackdown on dissent and critical voices in a country where artists have been harassed and detained for decades.” Would you agree with their assessment?

TB: Absolutely. This is the real goal of Decree 349—it even says that the artworks must follow ethical and revolutionary principles, but those are not described anywhere in the text nor linked to any other document to be consulted. In case you want to do your art “within the law,” there are no guidelines. “You should know better” and “Be submissive and compliant to the government’s needs of the moment” seem to be the subliminal messages.

What the artists who now have the favor of the government do not see is that the permissive line always moves. Today they are within the law, tomorrow they may be outside of the law. Everyone is a potential dissident in the eyes of the Cuban government—they do not trust anyone, and less so artists.

JTP: CAA recently put out a statement of support for the artists and activists opposed to Decree 349. What advice would you give CAA members who want to help?

TB: I want to thank CAA for its support of our cause. It makes an immense difference because the Cuban government makes a lot of its internal decisions based on how they make them look internationally. Our only protection comes from organizations and people in the world who recognize our experiences beyond all the official propaganda. It is important that people, especially those who identify as leftists and progressives, realize that Cuba today is not the one from the 1960s, where it was full of humanistic promise. Now we have a Cuba where the law is not to establish justice, but to measure the loyalty to the government.

The “Cuban legal turn,” as I call it, is an effort of the government to look “respectable” while abusing its power. They have found the perfect tool, one that is universally understood: the outlaws. No more conversations about politics or sympathies for you—now you are a common criminal. The Cuban government doesn’t recognize political prisoners. You are accused of some common crime instead of the real one, which is political. This makes it murky for people to understand what is happening and to be able to show solidarity. The conversation will shift from political rights to if anyone has ever seen the person in question taking drugs, stealing, molesting someone, or making a public scandal. Doubt then takes over your judgement [as the onlooker], and you may think twice before supporting a freedom fighter because you feel uncomfortable about the issues they are falsely accused of. That’s all the Cuban government needs from you, the ones outside of Cuba, the ones who can put pressure on them. That is why no dissident, and now no artist, will be ever accused of political motivation but rather for criminal offenses. What people need to know is that Decree 349 is not a law, but a way to stop the growing unified artistic movement for freedom of expression in Cuba. They need to understand that the law in Cuba is selectively applied to those uncomfortable to the government.

In these times, when totalitarian efforts are shamelessly growing around the world—specifically in the United States with Trump—we cannot get tired in front of injustice. We can’t forgive any injustice, no matter how small, because the next one is built on top off it.

JTP: Thank you. And to let our readers know, what are the projects you yourself are working on currently?

TB: I’ve been working on the Turbine Hall commission at the Tate Modern, which will be on view until February 24th, and on some new artworks to be shown in India, Italy, the UK, Sweden, and Mexico. I also just launched a new series of works focused on Trump and will soon do some new performances against Decree 349.

JTP: Anything else you would like people to know?

TB: Cuban artists are leading the fight for freedom of expression and we are not going to stop.You can support us by joining our petition to abolish Decree 349. Click here to sign.

Thank you!