Programs » Annual Conference

2010 Distinguished Scholar Session

Bryan J. Wolf is the Jeanette and William Hayden Jones Professor in American Art and Culture at Stanford University in California. He serves as the codirector of the Stanford Arts Initiative and the Stanford Institute for Creativity and the Arts.

Jules David Prown

Jules Prown, Paul Mellon Professor Emeritus of the History of Art at Yale University

Ralph Waldo Emerson’s famous salvo to Walt Whitman, “I greet you at the beginning of a great career, which yet must have had a long foreground somewhere,” rings true a century and a half later about the writing and influence of Jules David Prown, a devoted teacher of the history of American art and material culture at Yale University. His remarkable career marks the coming of age of American art history. His two-volume study of the painter John Singleton Copley (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1966) overturned the usual concerns of positivistic biography. His growing focus during the next several decades on the formal properties of objects, together with what he termed the system of cultural “belief” embedded within them, led to a methodological revolution that still resonates loudly in classrooms wherever American art and material culture are taught.

In the early 1950s, when Prown arrived at Harvard to study art history, American art seemed more an oxymoron than a field. The leading scholars of American art, such as Lloyd Goodrich and Edgar P. Richardson, were in museums rather than academia, and the subject was not taught at the university level by trained Americanists. Prown began to focus on American art in the master’s program at Winterthur, which emphasized the decorative arts. Returning to Harvard, he turned for assistance to Benjamin Rowland, Jr., an Asianist, who encouraged younger scholars in their pursuit of things American.

Prown was one of the first of a generation of scholars—many of whom were supervised by Rowland at Harvard—who would provide for their students the formal training in American art history that they themselves had lacked, but also the happy circumstance of being a central figure within the “Founding Generation” of American art historians. What distinguishes Prown is the shift in his writing from the question of “What is American about American art?” to “What is art about American art?” The first question occupied students of American art, literature, and history throughout the 1960s. It simultaneously enabled the creation of American art history as a vital and often cross-disciplinary enterprise, but saddled the field with unacknowledged ideological blinders. The second question, articulated by Prown in the 1990s but present in his scholarship for over a decade before that, married American art to material-culture studies, enlarging the field of American art and providing it with a new means for addressing the question of culture in general.

John Singleton Copley, Paul Revere, 1768, oil on canvas, 35.125 x 28.5 in. Gift of Joseph W. Revere, William B. Revere and Edward H. R. Revere, 1930. 30.781 (artwork in the public domain)

Scholarship on American art in the 1960s tended to divide into two camps: those eager to claim an “American exceptionalism” for artists of virtually all eras of American history, and those determined to prove the former wrong, largely by tracing the European antecedents for traits otherwise labeled “American.” Prown’s two-volume Copley book, which grew from his dissertation on English Copley, coincided with the catalogue he authored for a comprehensive exhibition of Copley’s work at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, the Metropolitan Museum in New York, and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Prown’s approach to Copley was to replace what in fact was a cold-war battle over American exceptionalism with science and statistics. He used a computer—I believe that he was the first art historian to do so—to “analyze data on 240 of Copley’s American sitters, correlating such factors as religion, gender, occupation, place of residence, politics, age, marital status, wealth, size of canvas, date, and medium.” An early paper he presented at CAA describing the project began with a slide of an IBM punch card. The audience “hissed,” as Prown later recounted, albeit with humorous intent. “The chairman of my department at the time advised me to remove the computer-analysis section from my book manuscript because its publication would jeopardize my chances for tenure.”

The Copley book provided readers with a magisterial overview of this painter as a citizen of the British trans-Atlantic. Prown’s vision deftly sidestepped both sides of the American exceptionalism debate by insisting—decades before transnationalism would emerge as a focus of scholarly studies—on the complicated and hybrid relations between English-speaking cultures on either side of the Atlantic. Prown’s goal was not to deny characteristics that might be considered uniquely American, but to ground them in a rich—and scientifically supported—account of the ways that local situations nest themselves within larger international currents.

Prown’s Copley study had another imperative driving it. The book provided American art history with a genealogy, a “foreground somewhere” that said, in effect, this is where the story begins. It lent the history of American art a clear narrative arc at a moment when the “flowering” of American art tended to be considered a product of the twentieth century, the “triumph” of Jackson Pollock and Abstract Expressionism. Prown’s Copley volumes pushed that conversation back two centuries, planting American art firmly in the soil of the eighteenth century and, in the process, providing students of American art with a new way to imagine their own scholarly narratives. Prown argued that “The essential character and strength of American art is not the result of independence from the Western artistic heritage: rather it results from the intense, almost greedy, drive on the part of American artists to absorb as much of that heritage as possible while at the same time, with enterprise and ingenuity, transmuting it into artistic statements that are distinctively, if not always consciously, American.”

Benjamin West, The Death of General Wolfe, 1770, oil on canvas, 60 x 84½ in. (152.6 x 214.5 cm). National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Transfer from the Canadian War Memorials, 1921 (Gift of the 2nd Duke of Westminster, England, 1918). National Gallery of Canada (no. 8007) (artwork in the public domain)

Those four penultimate words, “if not always consciously,” would grow over time into the engine that would drive Prown’s innovative art history. They led to a vision of objects as possessing an often hidden life of their own, survivors from the past with a tale to tell. The language for understanding that tale was the language of “form.” Prown accommodated the formalism that dominated so much of art-historical discourse in the years after World War II by lending it historical heft. The internal elements of a painting or artifact created something more than an abstracted system of colors, forms, and textures. They embodied the voices of the past. “If not always consciously” came to mean the hidden ways that history speaks through the objects that survive it. In 1980 Prown published his deeply influential article “Style as evidence,” followed two years later by “Mind in Matter: An Introduction to Material Culture Theory and Method.” Together the two essays formed a clarion call for scholars to look closely at objects, to identify the “synchronic” elements that recur in artifacts of the same era, and to deduce from those stylistic features the shape of historical belief that they express.

Just as Prown had reinvented “formalism” as a historical methodology, he similarly converted the tradition of Anglo-German object-based scholarship into a new and different type of object studies. Prown took the tenets of the New Criticism seriously (he had studied Cleanth Brooks and Robert Penn Warren while an English major in college). He asked, in effect, how an image could be explicated like a poem, and he answered his own question by inventing a method that insisted that all historical generalizations be tethered to an attentive reading of the object’s internal grammar. The goal was to preserve the integrity of close reading and stylistic analysis from the temptation of turning objects into merely illustrations. Like a good psychoanalyst, Prown wanted to let the patient do most of the talking. He felt that there was always an unconscious language echoing through the words—or in art history’s case, the style—of the object. “When formal properties are shared as a style by clusters of objects from one time and place, that style acts as a kind of cultural daydream expressing unspoken beliefs—a matrix of nonverbal or preverbal feelings, sensations, intuitions, and understandings that are shared in any given culture. Discerning and analyzing the form of things, where beliefs are encapsulated, is akin to having access to a culture’s dream world.”

For Prown, style is simply the material form that belief takes. It can be located anywhere human beings modify nature. At the historical moment when postmodernism, as an art movement, was blurring the differences between “hi and lo,” Prown was translating the language of an older art history tied to connoisseurship and iconography into an object-based praxis that went out into the world in search of belief and came back with style, that Midaslike touch that all societies create whenever “mind” comes in contact with matter.

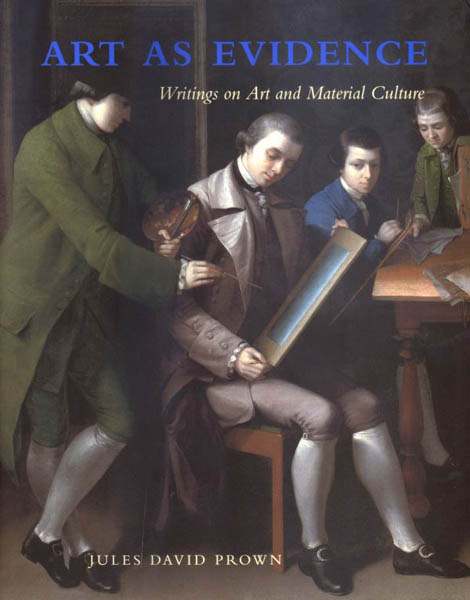

Jules Prown, Art as Evidence (2001)

Putting his own belief into practice, Prown coedited American Artifacts: Essays in Material Culture (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2000), with Kenneth Haltman. The book proudly displays the work of Prown’s former students in his material-culture courses at Yale. The following year he published an influential collection of his own essays, Art as Evidence: Writings on Art and Material Culture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001), an anthology that muses on the fate—past and future—of American art history, and ranges gracefully over the careers and images of many of Prown’s favorite artists: John Singleton Copley, Benjamin West, Charles Willson Peale, Raphaelle Peale, Winslow Homer, and Thomas Eakins.

Prown has thus served as a Founding Father twice over. The first time round he helped inaugurate American art history as a scholarly field, lending it a narrative shape that would guide several generations of students. The second time, as charmed as the first, he created a method as much as a field. He took the “capital C” out of culture; he installed “high art” among vernacular forms; and he maintained throughout what has always stood at the center of his intellectual life: a love for objects that is at the same time an endless curiosity about the people who made them.

Chicago Session

Generously funded by the Terra Foundation for American Art, the 2010 Distinguished Scholar Session took place on Thursday, February 11, 2010, 2:30–5:00 PM in Grand EF, East Tower, Gold Level, Hyatt Regency Chicago.